In the first seven parts of this series we investigated the statement in Burke’s Landed Gentry that the Rev. Oliver McCausland of Strabane in Ireland claimed to be “Chief of the clan of the Macauslanes, of Glenduglas, in Dumbartonshire”.

We concluded that Oliver McCausland of Strabane had not redeemed the mortgage on the McAusland Barony, and even if he had become Baron, as the senior member of a junior McAusland line, he would not have become Chief of the McAusland Clan.

We further concluded that the 1707 Colquhoun deed of Tailzie meant that the McAusland lands were integrated in to the Colquhoun Barony of Luss, that these lands could not be divided, and that the lands could not be sold. Therefore the 1707 Tailzie would have made it impossible for the McAuslands to redeem the mortgage on their baron and buy back their ancient lands.

In this, Part 8, before attempting to identify the ten McAuslands who signed the 1711 letter, in particular Dougald McAuslane, who described himself as the nearest heir, we look at various properties associated with the McAuslands and the rank of the people who may have signed.

The Importance of the Tacksman

It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the individuals who actually signed the 1711 letter from Wester Kilbryde in Glenfruin. However it seems likely that those involved would be local men, and quite possibly they may have been influential relatives of the last Baron, and of Oliver McCausland of Strabane. The signatories may have been the late Baron’s Tacksmen, or their successors, and it is useful to consider here what role Tacksmen played in the clan structure.

The Tacksman would often be related to his landlord and be the representative of a cadet branch of the extended family of the clan chief. Although a tacksman generally paid a yearly rent for the land let to him (his “tack”), his tenure might last for several generations. The tacksman in turn would let out his land to sub-tenants, but he might keep some in hand himself.

“In the Scottish Highlands, each clan chief or laird was related to all the farmers and peasants around him, and everyone knew it. His close male-line kin were tacksmen, holders of ‘tacks’ or releases of reasonable-sized tracts of the clan’s lands. The tacksmen tenanted these with their own junior kindred – who were in turn slightly more distant relatives of the laird. The junior offspring of the tenants were the peasant labourers. Each family knew their genealogy back to the chief ‘s family and bore his surname: he was the chief of the name, and in times of war, his extended family of tenants and sub-tenants provided the manpower for his personal army.

Therefore, possession of the surname of an aristocrat can well indicate that the family concerned is a junior branch of a noble line. In Highland Scotland, as also in Ireland, it is a virtual certainty.“

Anthony Adolph.

In 1825, James Mitchell described the nature of the relationships between the chief and his tacksmen, who were generally his relatives.

“A certain portion of the best of the land [the chief] retained as his own appanage, and it was cultivated for his sole profit. The rest was divided by grants of a nature more or less temporary, among the second class of the clan, who are called tenants, tacksmen, or goodmen. These were the near relations of the chief, or were descended from those who bore such relation to some of his ancestors. To each of these brothers, nephews, cousins, and so forth, the chief assigned a portion of land, either during pleasure, or frequently in the form of a pledge, redeemable for a certain sum of money. These small portions of land, assisted by the liberality of their relations, the tacksmen contrived to stock, and on these they subsisted, until, in a generation or two, the lands were resumed, for portioning out some nearer relative, and the descendants of the original tacksman sunk into the situation of commoners. This was such an ordinary transition, that the third class, consisting of the common people, was strengthened in the principle on which their clanish obedience depended, namely, the belief in their original connexion with the genealogy of the chief, since each generation saw a certain number of families merge among the commoners, whom their fathers had ranked among the tacksmen, or nobility of the clan. This change, though frequent, did not uniformly take place. In the case of a very powerful chief, or of one who had an especial affection for a son or brother, a portion of land was assigned to a cadet in perpetuity; or he was perhaps settled in an appanage conquered from some other clan, or the tacksman acquired wealth and property by marriage, or by some exertion of his own. In all these cases he kept his rank in society, and usually had under his government a branch, or subdivision of the tribe, who looked up to him as their immediate leader, and whom he governed with the same authority, and in the same manner in all respects, as the chief, who was the patriarchal head of the whole sept.“

James Mitchell, The Scotsman’s Library (1825), page 260.

In his 1775 book, Dr Samuel Johnson defined the Tacksman class:

Next in dignity to the laird is the Tacksman; a large taker or lease-holder of land, of which he keeps part as a domain in his own hand, and lets part to under-tenants. The tacksman is necessarily a man capable of securing to the laird the whole rent, and is commonly a collateral relation. These tacks, or subordinate possessions, were long considered as hereditary, and the occupant was distinguished by the name of the place at which he resided. He held a middle station, by which the highest and the lowest orders were connected. He paid rent and reverence to the laird, and received them from the tenants. This tenure still subsists, with its original operation, but not with its primitive stability.”

Samuel Johnson, A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775).

In 2020, Scottish Crime novelist Denise Mina and English comedian Frank Skinner recreated the journey for a three part television series. I was lucky enough to meet Denise in Edinburgh some time later and talk to her about their adventure and her books.

The three fundamental obligations traditionally imposed on tacksmen were:

- grassum (a premium payable on entering into a lease),

- rental (either in kind, or in money, which was designated “tack-duty”), and

- the rendering of military service.

Next we will look at some of the properties that were associated with the McAuslands prior to 1711, when the letter was written.

Properties Associated With The McAusland Barons

The road through Glenduglas follows the magenta arrow, while the road through Callanachglen follows the red arrow. Two of the main McAusland properties, “Callanach” and “Presshellach” (aka Prestelloch) are indicated with green arrows.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

As noted previously, Alexander, the 24th and last Baron in our reckoning, was named in a sasine dated 20th May 1664 of the £8 land of Caldenoch, Prestellach, Innerquhonlanes and Craigfad, in Dunbartonshire, to Alexander McCauslane as eldest lawful son and heir of the late John McC of Caldenoch, on a precept of clare constat by Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, signed at Rosdhu, on 16th May 1664.

We will look at each of these four properties in turn.

Caldenoch/Callanach

Caldenoch (Callanach) and Prestellach (Preshellach) were located in Callanachglen, between Glen Mallan, and Glen Douglas, in the Parish of Luss. For additional information on these properties see the excellent reports on Cùlanach and Preas Seilich published by North Clyde Archeology Society.

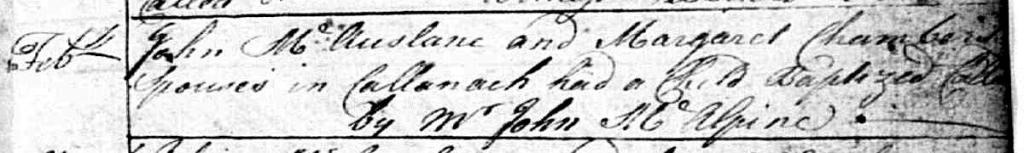

Caldenoch was the seat of the McAusland Barons and it should be noted that although the barony was sold to the Colquhouns of Luss, McAuslands continued to be born at Caldenoch until 1738. In that year, John McAuslane and Margaret Chambers, spouses in Callanach had an unnamed child of unknown sex baptised by Mr John McAlpine. (It is not clear whether the clerk forgot to add the name of the child, or whether, as sometimes happened, a dead baby was baptised before being buried.)

MCAUSLANE —– JOHN MCAUSLANE/ANN MCAUSLANE U 28/02/1738 499 10 / 119 Luss. Copyright National Records of Scotland.

A number of further births occurred in Caldenoch until 1801, the last known being Janet McDougal, daughter of John McDougall and Nancy Campbell, spouses in Callenoch, who was born in 1801.

As can be seen on John Wood’s 1818 map, the settlement of Prestellach is listed in what is by then called “Glen Gillanoch” presumably a derivative of Caldenoch, but Callanach/Caldenoch does not appear. By 1860, the Ordnance Survey Name Book referred to the ruins of Culanach, and quotes local authorities who stated that it had not been occupied for 40 years.

Prestellach

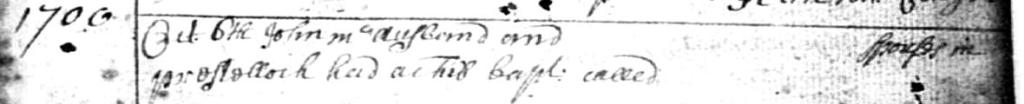

MCAUSLAND —– JOHN MCAUSLAND/ U 06/10/1700 499 10 / 10 Luss. Copyright National Records of Scotland.

The last known McAusland birth at Prestilloch was in 1700, when a John McAusland and his unnamed spouse (almost certainly Marie McFarlane) had a child of unknown sex baptised on 6th October.

They were not the last members of the McAusland family to live at Prestilloch. George McLellan and Janet McAusland had four children born at Wester Inverlaren (home to her great grandfather, Humphrey, the Kirk elder) between 1785 and 1790. They then moved to Prestilloch where they had an additional four sons between 1792 and 1798.

However, 1799 may have marked the end of the ancient McAusland link with Prestilloch when the McLellans received notice to quit:

“Precept of warning by Alexander Oswald of Shieldhall against tenants in Gortan, it runs: _

“Charge George McLellan, senior, residing in Preistelloch and George McLellan, junior, residing in Drumfad, to flit and remove themselves, their sub-tenants and cottars and dependants, and their families, servants, cattle, goods and gear furth of the lands of Gortan, extending to the 40/- land of old extent, with houses, biggins, etc, comprehending the lands commonly called Craggan and others, barony of Luss, parish of Row, against Whitsun next, 1799.”

Prestilloch continued to be inhabited as the 1841 census lists a Duncan McPhail, shepherd, his wife, two daughters and a servant living at Prestilloch, and in 1842, a third daughter named Elizabeth joined the family. However after that date there appear to have been no further births at Prestilloch and the place does not appear in the 1851 census suggesting that, like Caldenoch before, it had had finally been abandoned.

Craigfad and Innerquhonlanes

The location of Craigfad is uncertain. It might possibly be Craggon, between Callanach and Presshellach on the 1777 Ross map, but this is speculation.

It had been postulated that Innerquhonlanes might be the Inverohum in Glen Douglas in the 1777 Ross map above. Indeed, Alistair McIntyre and Tam Ward state that Innerquhonlanes is the scribe’s rendering of “at the confluence of Conglens”…. The settlement of Conglens took its name from the Conaglen, a side-glen of Glen Douglas.

Perhaps the ancestors of Irish McAuslands once lived at Innerquhonlanes in Glen Douglas, and this might be the basis for the assumption by later biographers that the McAusland Barony had been based in Glen Douglas rather than at Caldenoch.

Alderigan

Alderigan is another less-known property that seems likely to have been owned by the McAusland Barons. It appears as “Ardergadan” to the south-west of Callanach on the 1777 Ross map above.

In a document dated 2nd January 1813 listing Hearth Valuations in the reigns of Charles or William & Mary, “Alduergan” appears above four McAusland properties: “Chaldenach“, “Craigfad“, “Dawn or Prestillagh” and “Conglens“.

The estimable North Clyde Archeology Society have published an excellent informative report entitled “The history and survey of Alderigan settlement in Argyll” by Alistair McIntyre (History) and Tam Ward Archaeology). In it they note that: “Alderigan takes its name from the Alt Derigan, a tributary stream of the Mallan burn, beside which the remains of the settlement are located. The Gaelic name translates as “red burn”, almost certainly derived from the iron-stained colour of the water.“

Their report supports our assumptions, stating: “1844 A Luss Estates rental states that Alderigan, along with Prestelloch and Stronmallanach, are believed to have once been owned by a Baron McAuslan (Note that in a Dumbarton County Valuation of 1657, Baron McAuslan’s lands are listed as valued at £80 in the Parish of Luss, out of a total valuation of £2234.“

They also report that “It does seem likely that the lands of Alderigan reached the stage where they were subsumed under the much more prominent adjacent settlement of Culanach, once the seat of the McAuslans of Culanach, who styled themselves “Barons”. In 1776, an inventory of farms then owned by Luss Estates makes no reference to Alderigan, in contrast to Culanach. Further, Ross’s Estate map, drawn up around the same time, depicts cultivated land stretching continuously between the two places, lending support to this interpretation. It is possible that although Alderigan is not listed as among the farms in 1776, it was still inhabited, but not as a farm, which could explain its absence. (People by the name of White are listed a little later at other places, where their livelihood is given as that of handloom weaver). Even so, the lack of entries in LOPR’s prior to that date still presents something of an enigma. Is it possible that births/baptisms/marriages were always ascribed to Culanach, even when Alderigan was inhabited? However, comparison with other places suggests that the records are generally faithful to specific places of residence.“

McAusland Properties in Glen Fruin

Stockidow, Kilbride & Inverlaran

Extracted from Charles Ross’ 1777 map of Dunbartonshire. Used with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

There were a number of other properties linked to the McAuslands. Some of these located in Glen Fruin are noted in the map above. These are (Easter and Wester) Kilbryde, (Kilbryde being the address on the 1711 letter); Stockidow, the ancestral home of Peter McAuslan, who by family tradition was a descendant of the Barons, and the subject of a biography by Polly Aird; along with (High or Wester) and (Low or Easter) Inverlaran, the former being home to Humphrey McAuslan, Elder of the Kirk.

Stockidow

Stockidow is notable as the farmstead occupied by the ancestor of Peter McAuslan, who believed he was a descendant of the Barons. On 14th April 1905 he wrote a letter mentioning that his grandfather was “either a son, or a son’s son of him who was called Baron McAuslan who owned an estate called ‘Stookadoo’ at Luss that he sold to a man named Calhoun while he was under the influence of liquor.“

Peter joined the LDS sect and emigrated to the USA where he had an eventful life, which has been the subject of a biography by his relative, American author, Polly Aird.

As with other properties, little now remains of Stockidow. Wet weather did not permit Polly Aird and her daughter to visit in 2010, as the ruins lay on the wrong side of the Fruin Water from the modern road.

Stockidow was also listed as the ancestral home of the McCauslands of Newlandmuir in their 1863 grant of arms, suggesting that the two families were closely related.

Inverlauren

Inverlauren was inhabited by McAuslands from father to son from at least 1694 until 1876, with a daughter then living there from 1876 until at least 1901. The first documented McAusland living there was Humphrey McAusland, an elder of the Kirk of Scotland. His son Archibald is buried in Rhu kirkyard with a gravestone that features a very faded coat of arms.

Kilbride

Easter and Wester Kilbride were between Stockidow and High or Wester Inverlauren. Wester Kilbride is notable as the place named on the 1711 letter. In the 1740s, Humphrey McAusland in Inverlauren (grandson of the Kirk elder of the same name) appears to have farmed Wester Kilbride during his father’s lifetime. In the 1690s, Wester Kilbryde was the home of a John McAusland whose descendants moved south to Kilmahew and other places such as Lyleston and Gelistoun in Cardross parish. One of John’s sons, or possibly a brother, named Duncan complained to the Kirk Session in 1714 after Duncan’s wife, Anna Campbell, was described as a whore by a neighbour, Margaret Colquhoun from Inverlauren, and was accused of having had an illegitimate child. The case went on for some considerable time.

Other places associated with the McAuslands

Drumfad, Blairnaire, Strone, Dumbarton, Kilmahew, Lyleston & Geilston

The McAuslands spread not just to Ireland, but all over Scotland with the first baptisms being recorded in the Old Parish Registers in 1658 in Glasgow, in 1681 in Cardross, in 1682 in Dumbarton, in 1683 in Bonhill, in 1694 in Lochgoilhead, in 1698 in Luss, in 1701 in Greenock, in 1704 in Kilmaronock and in 1711 in Port Glasgow, and there were likely McAuslands living in these places before these records.

Despite being in neighbouring parishes, Drumfad (in Row parish ) and Wester Inverlaren (in Luss parish) were adjoining with the river Fruin between them and there is autosomal DNA evidence suggesting that the families who lived at these locations were related.

Blairnaire – “Blairnarin”, just to the north of Wester Kilbride, was also associated with the McAuslands. On 11th September 1619, a “Patrick McCausland in Blairnare” was witness to a “Sasine of the 5 merk land of Auchinvennell in Lennox … on a precept of clare constat by Ludovick, Duke of Lennox…”

On 7th February 1666, “Patrick McCauslane in Strone” (of Luss) was witness to a “Sasine of the 46/8 land of Wester Lettirowall in Row parish” from Sir John Colquhoun.

On 30th May 1684, Duncan MacAuslane, a mason burgess of Dumbarton, was contracted by John Colquhoun, 12th of Camstradden to make a three storey addition to the tower of Camstradden.

Prior to 1711, there were also McAuslands living in Cardross parish at Kilmahew (owned by the Napier Barons of Kilmahew), Lyleston and Geilstoun (The Donald family lived at Auchensail, Cardross, in the 1620s, then at Lyleston House in 1707, at Darleith in 1713, and finally at Geilston in 1757).

Changes to Parish Boundaries

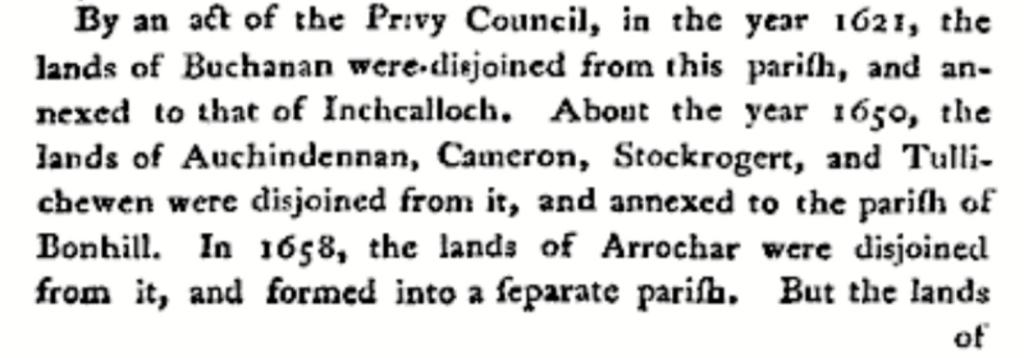

It should be noted that while Caldenoch, Prestilloch and Inverlaran were, at the time of the 1711 letter, in the parish of Luss, Kilbryde and Stockidow in Glen Fruin were in the adjoining parish of Row (or Rhu).

Copyright University of Glasgow, University of Edinburgh.

Copyright University of Glasgow, University of Edinburgh.

However, there had been significant boundary changes in the 1600s. In 1621 the Buchanan lands (mostly to the east of Loch Lomond) were transferred from Luss parish to Inchcalloch, which was subsequently renamed Buchanan parish. Then in 1655, the McAusland lands of Caldanach, Prestelloch and Conglens (which are assumed to have been transferred with the Buchanan lands to Inchcalloch in 1621) were returned to Luss parish.

Conclusion

Having thus determined some of the places where the signatories of the 1711 letter to Oliver McCausland may have lived, and looked at their possible rank – i.e. Tacksmen and relatives of the chief- within the McAusland sept of Clan Buchanan, in Part 9 we will look at the information available in the Hearth Tax Records and Old Parish Registers.

Thanks to Brian Anton, Matthew Gilbert, Michael Barr, Dave McCausland and others for helpful discussions and sharing their research.