Scottish Feudal Baronies

According to Wikipaedia, “In Scotland, a baron is the head of a feudal barony, also known as a prescriptive barony. This used to be attached to a particular piece of land on which was situated the caput (Latin for “head”) or essence of the barony, normally a building, such as a castle or manor house. Accordingly, the owner of the piece of land containing the caput was called a baron (or baroness). According to Grant, there were around 350 identifiable local baronies in Scotland by the early fifteenth century and these could mostly be mapped against local parish boundaries.“

Scottish Barons, from The Napers of Kimahew (1849)

The degrees of hereditary dignity in England, are six, — Baronet, Baron, Viscount. Earl, Marquis, Duke ; — in Scotland, they are seven — Baron, Baronet, Lord, Viscount, Earl, Marquis, Duke. Prior to the reign of James VI., the nobility of Scotland consisted of three grades, —Earls, Lords, and Barons. The latter, styled sometimes free barons, small barons, and lesser barons, formed the most numerous, and not least powerful section of the Proceres Regni. They had hereditary seat and voice in Parliament inter magnates; were styled “Lovit Cousin,” by the King; were called ” noblemen” in Acts of Parliament had ascribed to them the courtesy style “right

honourable” had the right of pit and gallows” within their respective baronies ; and enjoyed, by statute, Parliamentary robes and ornaments of estate, similar to those of the ranks above them. They also carried de jure supporters to their arms.

Before the Union, Parliament was composed of three estates, viz. : — the Clergy, the Nobility, and the Burgesses. These all sat in one house, according to their respective ranks, whether ecclesiastical, territorial, or municipal. The term comprehending the second estate, “the nobility,” and the modern word “peerage,” are not to be con- founded with each other. The latter now implies only those hereditary classes that rank above the baronetcy, which was a rank invented by James VI., and originally conferredfor a certain price.

The Statutes of Robert I bear to be made in his Parliament, with – “Earls, Barons, and others, his noblemen of his realm;” and so late as 1592, the 134th Act of James VI begins, “the Nobility, Earls, Lords, and Barons, &c.” In the 87th Act, 6th Parliament of James V, it is ordained that ” everie nobleman, sic as earle, lorde, knight, and barone,” &c. Sir George Mackenzie, Lord Advocate of Scotland under Charles II and James II (& VII), in his celebrated work on Precedency, observes “Under the word baron, all our nobility are comprehended. and he states: - ”I find by the old records, as particularly in October, 1562, that noblemen and burgesses are called, but no barons – the barons and noblemen being then represented promiscuously.” By the 101st Act, 7 Parliament of James I., the barons of each shire were allowed to choose two of their number to represent them, “which,” continues Sir George (who died 1691), “is the custom at this day.” “Yet,”say she,”it is observable, that though by that act the barons may, for their conveniency, choose two, yet they are, by no express law discharged to come in greater numbers.”

This was James I. of Scotland, not James I. of England; accordingly, in the reign of Queen Mary, when the estates assembled for ratification of the Confession of Faith, in 1560, the barons claimed their right to have seat and voice in Parliament, intimating their desire to exercise the same, which was unanimously allowed.

The titles of hereditary dignity in Scotland were originally territorial. Thus lands were erected into baronies, giving the title of baron; into lordships, giving the title of lord ; and into earldoms, which gave the title of earl. Barony was truly and strictly, however, the only feudal dignity conferred on territorial proprietors ; lordship, earldom, &c, being only nobler titles for a barony, as connected with personal dignities. (Stair, II., 3, 60. Erskine, II. 3, 46, and 6, 18.) As these were the constituent portions of the second estate of the realm, it does not appear how the barons allowed their rights to fall into disuetude. No act of the legislature was ever passed by which they were disfranchised; for the consent given by James I., that the barons of each shire should be represented by two of their number, merely relieved them from the great trouble, and very grievous expense, occasioned by their attendance in Parliament. It was, in fact, on a representation of the hardship of this expensive honour, that the King allowed the barons to appear by representatives; or rather agreed, as Pinkerton says that a baron should “not be constrained to attend, except his estate amounted to a certain sum.”

These noble deputies were even paid for their attendance in the Legislature ; and perhaps one of the most curious and interesting documents among the Kilmahew Papers, (especially now-a-days, when payment of members is so much scouted, sneered at, and despised, as one of the six points of the Charter,) is the ” Horning and Poynding, Sir John Colquhoun and John Napier, Members of Parliament, chosen for the shire of Dumbartane, against the free-holders of the said shire, for the £5 scots, daylie allowance, modified by Parliament, which is signet at Edinb. 22 feb. 1662,” accompanied by the ” Certificate for the saids Commissioners Their Sitting in Parliament 1661, Extracted furth of the Rolls of Parliament by Hamilton.

Rights of blood do not prescribe, and it is, therefore, somewhat remarkable, that the barons of Scotland, numbering even at this day, (1848,) perhaps 400, should have allowed their rights, privileges, and distinctions, to remain so long unrecognised, and even unknown, while the comparatively modern baronetcy has never ceased an agitation, as yet fruitless, for a recognition of its claims to certain shadowy baronies in Nova Scotia, and valueless rights to trifling personal decoration.

The Acts of Union and of the Scottish Legislature, regulating the elections of the Representative Peers and Commissioners for Scotland, made no express provisions beyond those of 5 Feb, 1707; when it was enacted that of the forty-five members to be sent to .the House of Commons, thirty should ” be chosen by the shires or stewarties, and fifteen by the Royal Burrows and that the sixteen Peers and forty-five Commissioners for Shires and Burghs, who shall be chosen by the Peers, Barons, and Burghs, respectively, in this present Session of Parliament, and out of the members thereof, in the same manner as Committees of Parliament are usually now chosen, shall be the members of the respective Houses of the said first Parliament of Great Britain.

Against the articles of Union, and pending their discussion, the Earl of Buchan protested for the privileges of the Peers, the Duke of Argyll for those of the Peerage, the Baronage, and the Burgesses, and George Lockhart of Carnwath, that neither votes, conclusions, nor articles, should “prejudge the Barons of this kingdom from their full representation in Parliament, as now by law established, nor any of their privileges, and particularly their judicative and legislative capacities &c.

These “judicative” capacities were swept away by the act, abolishing heritable jurisdictions, passed immediately after the vindictive and bloody suppression of the rising in 1715 ; a measure, which, however politic in the then state of Scotland, wise in a national point of view, and fortunate in its results, was at least somewhat unjust, so far as regarded the personal rights of the Barons. The power of “pit and gallows” was happily gone, but the crown vassals, infeft cum curiis, may still hold a court for pleas not exceeding 40s. fine to the amount of 20s.; and imprison in the stocks five hours in the daytime within their own feudal jurisdictions.

Their ” legislative” capacities, since the Union, were, till the Reform Act, exercised by the “freeholders” in the counties, electing commissioners to Parliament as before and the debates in the House of Commons of 1832, as well as of previous years, prove how extensive was yet their political influence.

These electoral privileges, however venerable or respectable, were then committed to every proprietor, whatever might be his tenure, of property yielding him £10 sterling yearly. The justice of that change, as affecting the personal interests of the freeholders, has often been controverted. Freeholds, from having been a sacred trust for the people at large, had become marketable property, of great value, and in constant demand. This had long been sanctioned by law. Yet, without reservation or compensation that property was at once swept away, and, in some counties, what had been eagerly sought at the price of £2000, in 1830, ‘was, in 1832, worth nothing! The policy of the new mode of representation is best judged of by its results, on which, be it remarked, scarcely two men can be found to agree ; and it is, perhaps, not going too far to remark, that although the embittered, and all but extinguished free-holder may now sneer to see the immuni- ties of a “lovit cousin” of Majesty vested in the presiding lord of a village whisky shop ; the parish ” Stultz,” profound only in fustians, ruminating on the newly-acquired privilege, held formerly by those only who had “robes of estate;” or the master weaver holding out to the laudable ambition of shoeless apprentices their future possession of the franchise, conferred by the occupancy of a floor-less loom-shop, and the chance of thereby wielding the rights of the former Proceres Regni ; still it can by no one (however fervent his hopes of the new constitution) be denied, that the classes, who acquired the legislative capacities of the ancient Barons, were the first to raise their voice against that political party who had bestowed on them their new electoral powers, and that, in 1843, many not only will not exercise the rights so conferred, but even fervently desire to be unpossessed of what is to them a troublesome privilege. Whatever may be thought, however, of this great political change in the constitution of the country, it is earnestly to be hoped that the franchise will never again become property, as it was in the time of the Barons, and their representatives, the Freeholders, nor be made the subject of barter or sale, in any shape whatever.

In the words of a learned commentator on the Laws of England : — “It was the stern task of our forefathers to struggle against the tyrannical pretensions of regal power to us, the course of events appears to have assigned the opposite care, of holding in check the aggressions of popular licence, and maintaining inviolate the just claims of the prerogative. But, in a general view, we have only to pursue the same path that has been trodden before us,—to carry on the great work of securing to each individual of the community as large a portion of his natural freedom as is consistent with the organization of society, and to increase to the highest degree, that the order of divine Providence permits, the benefits of his civil condition. A clearer perception of the true nature of this enterprise, of the vast results to which it tends, and of the obligations by which we are bound to its advancement, has been bestowed on the present generation, than on any of its predecessors. May it not fail also to recollect, amidst the zeal in- spired by such considerations, that the desire for social improvement degenerates, if not duly regulated, into a mere thirst for change ; that the fluctuation of the law is itself a considerable evil ; and that however important may he the redress of its defects, we have a still dearer interest in the conservation of its existing excellencies.”

The Barons of Argyll and the Norwegian Influence

It was not until the Treaty of Perth in 1266, that Norway finally relinquished its claim to the Hebrides and Man, and they became part of Scotland. And it was not until 1292 that Argyll was created a shire and “The Barons of all Argyll and the Foreigners’ Isles“, which had preceded the kingdom of Scotland, became eligible to attend the “Scots” Parliament – appearing in the record of the parliament at St. Andrews in 1309. This is of interest as the McAusland lands in Glen Fruin were on the border of Norse territory and modern day Luss is in the Argyll & Bute council area.

Indeed in 1263, under King Haakon IV of Norway, the Norse sailed to Arrochar then carried their boats between Loch Long and Loch Lomond at Tarbet, a narrow strip of land between the two lochs. As a result, the Vikings were able to turn Loch Lomond and invade the lands on the west side of Loch Lomond. The Norsemen returned to Arrochar with their plunder, but a hurricane wrecked many of their boats and King Haakon IV was defeated by the Scots at the Battle of Largs on 2nd October 1263. He died on 16th December 1263 at Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands, then part of the Kingdom of Norway.

There is an 11th century Viking Hogback Stone in Luss that is believed to date from the 1263 invasion.

The McAusland Barons of Caldenoch, Prestellach, Innerquhonlanes and Craigfad

The McAusland Barons were first mentioned in a historical document on 4th July 1395 when John McAuslane of Caldenocht witnessed a charter where Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss granted his brother Robert the lands of Camstradden. (Colquhoun of Luss charters). The fact that John McAusland was described as “of Caldenocht” is crucial as “of” a property implies having possession of a charter to that property, as opposed to simply just living there. The McAuslands were feudal superiors not just of Caldenocht (also known as Coldenocht, Caldenoth, Caldanacht, Caldenache, Caldonah, Callenach, Calanach, and Cùlanach) but also of Prestellach, Innerquhonlanes and Craigfad.(Campbell: Abstract of Argyll Sasines).

A number of McAusland Barons are documented, many of these listed in North Clyde Archaelogical Society’s excellent report The history and survey of several settlement sites in Argyll by Alistair McIntyre (History) and Tam Ward (Archaeology). However, it is difficult to attempt to construct a meaningful genealogy without any detailed knowledge these McAusland Baron’s dates of birth, succession and death, exactly how they were related to each other and whether the Barony was inherited directly from father to son, or to other relations. In the following list, the numbering of the Barons is my own interpretation, and is sometimes based on people for whom there is no documentary evidence.

Macbeath Macauslan, possible 1st Baron of Caldenoch

In page 164 of his Historical and genealogical essay upon the family and surname of Buchanan (1723), William Buchanan of Auchmar mentions “Macbeath Macauslan, proprietor of that little interest called the barony of Macauslan in the Lennox, who lived in the reign of king Robert III. and of whose uncommon stature and strength some accounts are retained to this very time.”

King Robert III (circa 1337 – 4 April 1406), born John Stewart, was King of Scots from 1390 to his death in 1406. However, a Johne MacAuslane of the Caldenocht was witness to a charter on 4th July 1395. Therefore, if Auchmar was correct, and this was not always the case, Macbeath Macauslan presumably died between the accession of Robert III in 1390 and 4th July 1395.

As noted in another article, BigY700 analysis has revealed that McAuslands of the chiefly line are members of haplogroup R-FGC32576, which could be associated with Sir Maurice Buchanan (or McAusland) of that ilk, 10th Chief of Clan Buchanan, and therefore MacBeath Macauslan may have been the son of Sir Maurice Buchanan, 10th chief of Clan Buchanan and younger brother of Sir Walter Buchanan, 11th chief of Clan Buchanan.

John McAuslane, possible 2nd Baron of Caldenocht, flourished 1395 to 1429

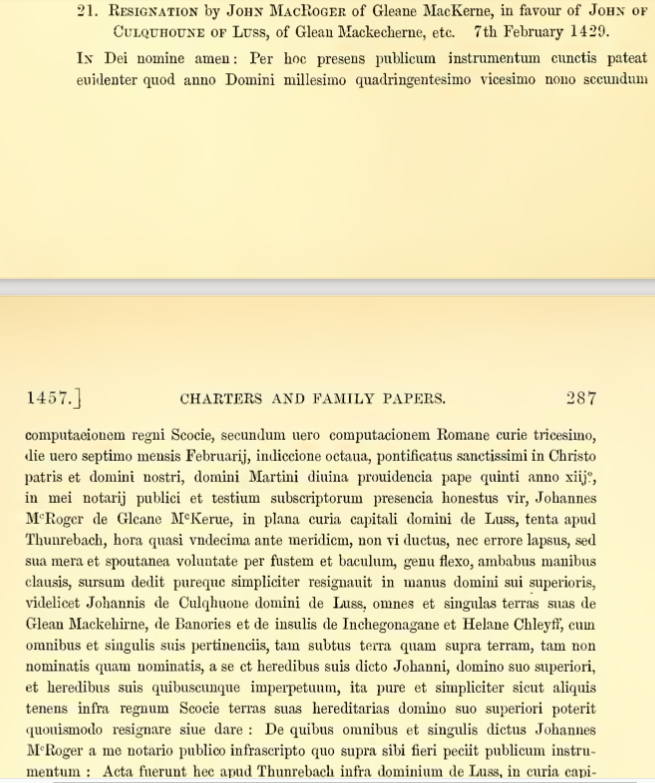

by Fraser, William, Sir, 1816-1898.

John McAuslane of Caldenocht witnessed a charter in 1395 where Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss granted his brother Robert the lands of Camstradden. (Colquhoun of Luss charters).

by Fraser, William, Sir, 1816-1898.

by Fraser, William, Sir, 1816-1898.

Witness, in 07 February 1429, as Johanne MacAusillane, domino de Callenach, to the resignation of Gleane MacKerne etc by John MacRoger in favour of John of Culquhoune of Luss. (Fraser: Chiefs of Colquhoun) (Assumed to be the same witness as in 1395, but could be a son or other relative).

Alexander McAusland of Caldenocht, flourished 1421

An Alexander McAusland is one of those recorded as killing Thomas of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Clarence at the Battle of Baugé on 22 March 1421. Clarence was the second son of King Henry IV of England, brother of Henry V of England, and heir presumptive to the English throne, and according to the Treaty of Troyes, also to the French throne, in the event of his brother’s death.

However, accounts state that “Clarence was unhorsed by a Scottish knight, Sir John Carmichael, and finished off on the ground by Sir Alexander Buchanan, probably with a mace“. In other versions of the incident, Sir Alexander kills the Duke by piercing him with a lance.

The confusion appears to have arisen as the early lairds of Buchanan very originally named McAusland of Buchanan and gradually went on to assume the name of their land as their surname with McAusland and Buchanan both being used for several generations. Therefore, the knight who killed the Duke of Clarence was essentially Alexander McAusland of Buchannan.

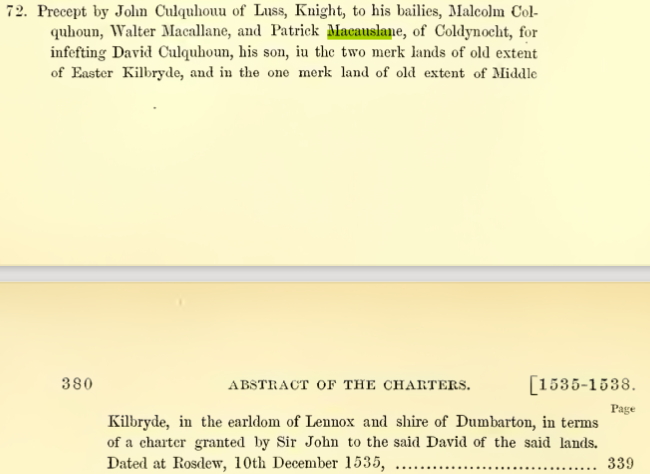

Patrick McCauslane of Caldenocht, flourished 1535 to 1543

On 10 December 1535 there is a charter in which mention is made of Patrick McAuslane of Coldynocht. (Fraser: Chiefs of Colquhoun).

In 1536, Patrick McCaslane of Caldanacht and his brother Donald are named as followers of the Earl of Argyll. (Black: Surnames of Scotland).

According to The chiefs of Colquhoun and their country; by Fraser, William, Sir, 1816-1898, “Mr. Adam Colquhoun of Blairvaddoch sold to Patrick M’Causlane of Caldenocht, and Marjory Colquhoun, his spouse, an annual rent of ten merks Scots, from the lands of Letterwald-mor ; and on 20th February 1543 they granted him letters of reversion, engaging, on his payment of one hundred merks Scots, to renounce this annual rent in his favour.“

Patrick McAwslane of Caldenache, flourished 1599 to before 1602

In 1599 there was a Deed of renunciation by Patrick McAwslane of CALDENACHE in favour of Sir Alexander Colquhoun of Luss of his claim to 2/3 of Stronmaleroch, Parish of Rosneath, Barony of Luss, in return for payment by Sir Alexander of 200 merks. (Colquhoun of Luss Estate papers, deed (box 7).

John McCaslane of Caldenoth, flourished 1602

CALDENOTH, the property of John McCaslane of CALDENOTH, is among the list of places despoiled in the so-called Glen Finlas Raid of December 1602. As well as various properties despoiled on Loch Lomondside, others so treated included places in Glen Luss, Glen na Caoruinn and Glen Mallan, most likely giving an indication of the route taken by the raiders as they made their escape northwards. (Fraser; Chiefs of Colquhoun).

There are suggestions that he may have died within a few days of the Battle of Glen Fruin which took place on 07 February 1603.

Patrick McAusland of Caldenoch, born ca 1580?

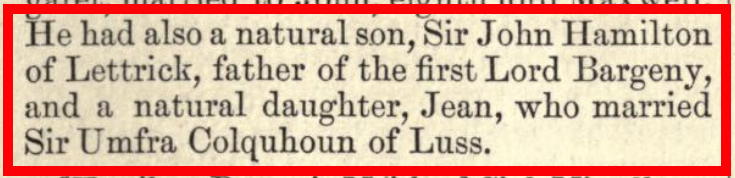

Stated in some genealogies to have been born in Glen Douglas in 1580 and to have married Agnes Colquhoun. She is said to have been the daughter of the Humphrey Colquhoun who was murdered by MacGregors at Bannachra Castle in June 1592 and “Lady” Jean Hamilton, daughter of John Hamilton, 1st Marquis of Hamilton and his wife Margaret Lyon, herself the daughter of John Lyon, 7th Lord Glamis and Janet Keith. (Mosley, Charles, editor. Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes. Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke’s Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003. Vol. 1 page 860.)

However, there are several inaccuracies in that story. Firstly, “Lady” Jean’s title is misleading as it seems that Sir Humphrey Colquhoun’s wife was not the daughter of the Marquis of Hamilton and his wife Margaret Lyon, but actually the illegitimate daughter and an unknown mother. (Dictionary of National Biography by Sir Stephen Leslie, published 1885-1900). She is however referred to as “Dame” Jean Hamilton, and outlived not just her first husband, Sir Humphrey Colquhoun, but also her second, Sir John Campbell, 7th of Ardkinglass, being alive in 26 July 1625. (Chiefs of Colquhoun and their country by Sir William Fraser (1869) Vol1 p 163).

Secondly, the Agnes Colquhoun who married Patrick McAusland was not the daughter of Sir Humphrey and Dame Jean Hamilton. The latter couple had three daughters, Jean, Margaret, and Annas, but no sons. During the attack on Bannachra Castle, it was reported that the MacGregors and their allies “brutally violated the person of Jean Colquhoun, the fair and helpless daughter of Sir Humphrey” and she is believed to have died son after 17 January 1593 (Chiefs of Colquhoun and their country Vol1). Meanwhile, Anna, “Youngest of the lawful bairns and daughters of the decessed Sir Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss” who was also known as Annas and Agnes, married Colin Campbell, son of Duncan Campbell of Carrick in 1610.

John McCauslane of Caldenoch, flourished 1657 to before 1664

A County Valuation Roll in 1657 put the value of Baron McCauslan’s holdings in the Parish of Luss at £80, out of a parish total of £2234.

Mentioned in an 1664 Sasine of £8 land of Caldenoch, Prestellach, Innerquhonlanes and Craigfad, in Dunbartonshire, to Alexander McCauslane as eldest lawful son and heir of the late John McCauslane of Caldenoch, on a precept of clare constat by Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, 20 May 1664. (Campbell: Abstract of Argyll Sasines).

Alexander McCauslane of Caldenoch, flourished 1664

Mentioned in a 1664 Sasine of £8 land of Caldenoch, Prestellach, Innerquhonlanes and Craigfad, in Dunbartonshire, to Alexander McCauslane as eldest lawful son and heir of the late John McCauslane of Caldenoch, on a precept of clare constat by Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, 20 May 1664. (Campbell: Abstract of Argyll Sasines).

The fortunes of the McAuslands appeared to go into decline under this last Baron.

Alexander McAusland, last Baron of Caldenoch, Prestilloch, Innerquhonlanes & Craigfad, flourished before 1718

Janet McAusland, heiress of Caldenoch, Prestilloch, Innerquhonlanes & Craigfad, flourished before 1718

The McAusand ownership of these lands came to an end some time between 1694 and 1718 when Janet McAusland, daughter of Alexander McAusland, last Baron of Caldenoch, Prestilloch, Innerquhonlanes & Craigfad, sold the lands to Sir Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss (1688-1718).

The sale of the Barony would appear to have happened prior to 1707, as there is a Register of tailzie, referring to Ann Colquhoun, or Grant, and listing a large number of properties, including “Couldenoch” (Fraser; Chiefs of Colquhoun).

Peter McAuslan, descendant of the McAuslan Barons?

Peter McAuslan believed that his grandfather or great grandfather was a son of the last Baron McAusland, who lost his lands to the Colquhouns of Luss.

References:

Mormon Convert, Mormon Defector: A Scottish Immigrant in the American West, 1848–1861 Hardcover – Illustrated, 30 Jun. 2009 Available for purchase on Amazon and other good booksellers.

Loch Lomond Clan Battles and Viking Raids.

[…] at Lammermoor entitled “The McAusland Barons of Caldenoch, Prestilloch, Innerquhonlanes and Craigfad”. Includes a nice chronological history of the barons […]

LikeLike