DNA testing is a powerful and relatively new way to confirm family relationships with a number of companies offering various services including ethnicity estimates, health and traits and cousin matching.

Collaborations

We are happy to collaborate with DNA matches to attempt to work out where we share common ancestry. (If you are a match on Ancestry DNA you will first need to send an invite to user: iainold)

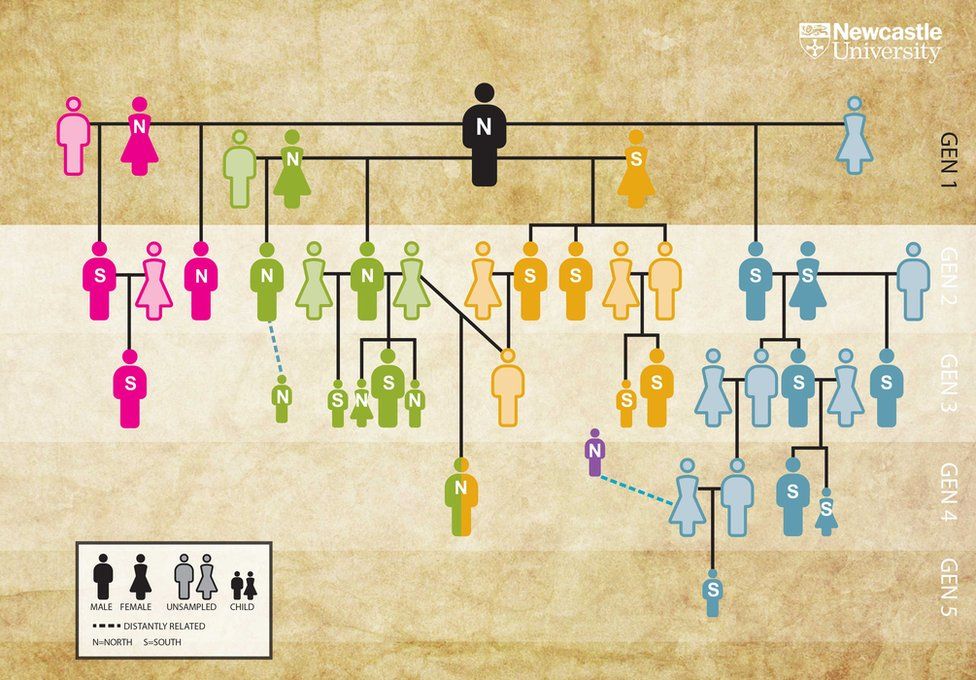

The Genetic Makeup of the Peoples of the British Isles

Due to the diverse nature of the inhabitants of these islands there can be difficulty in attempting to assign relatively modern labels such as “Scottish” or “English” to any segment of DNA. Indeed some of our DNA can be demonstrated to have rather surprising and ancient origins.

Neanderthals, Denisovans and other Hominins

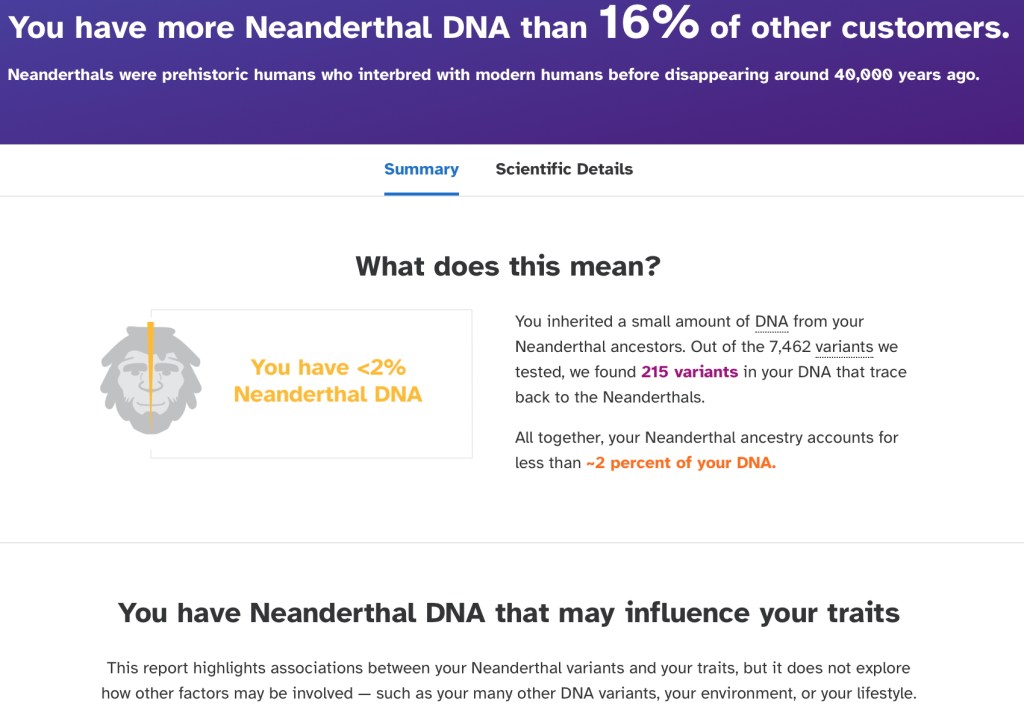

In May 2010, the Neanderthal genome project released a draft of their report on the sequenced Neanderthal genome which demonstrated a range of Neanderthal genetic contribution to non-African modern humans ranging from 1% to 4%. There is now evidence for interbreeding between archaic and modern humans during the Middle Paleolithic and early Upper Paleolithic. This interbreeding occurred in several independent events and included not just Neanderthals but also Denisovans and various as yet unidentified hominins.

In Eurasia, interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans with modern humans took place several times. The introgression events into modern humans are estimated to have happened about 47,000–65,000 years ago with Neanderthals and about 44,000–54,000 years ago with Denisovans.

Neanderthal-derived DNA has been found in the genomes of most or possibly all contemporary populations, varying noticeably by region. It accounts for 1–4% of modern genomes for people outside Sub-Saharan Africa.

Denisovan-derived ancestry is largely absent from modern populations in Africa and Western Eurasia. The highest rates of Denisovan admixture have been found in Oceanian and some Southeast Asian populations. An estimated 4–6% of the genome of modern Melanesians is derived from Denisovans, but the highest amounts detected thus far are found in the Negrito populations of the Philippines.

If we go back in time, several species of humans have intermittently occupied Great Britain for almost a million years. The earliest evidence of human occupation around 900,000 years ago is at Happisburgh on the Norfolk coast, with stone tools and footprints probably made by Homo antecessor. The oldest human fossils, around 500,000 years old, are of Homo heidelbergensis at Boxgrove in Sussex. Until this time Britain had been permanently connected to the Continent by a chalk ridge between South East England and northern France called the Weald-Artois Anticline, but during the Anglian Glaciation around 425,000 years ago a megaflood broke through the ridge, and Britain became an island when sea levels rose during the following Hoxnian interglacial.

Fossils of very early Neanderthals dating to around 400,000 years ago have been found at Swanscombe in Kent, and of classic Neanderthals about 225,000 years old at Pontnewydd in Wales. Britain was unoccupied by humans between 180,000 and 60,000 years ago, when Neanderthals returned.

Hunter-Gatherers

By 40,000 years bp (before present) the Neanderthals had become extinct and modern humans had reached Britain. But even their occupations were brief and intermittent due to a climate which swung between low temperatures with a tundra habitat and severe ice ages which made Britain uninhabitable for long periods. The last of these, the Younger Dryas, ended around 11,700 years ago, and since then Britain has been continuously occupied.

The Neolithic Farmers

Located at the fringes of Europe, Britain received European technological and cultural developments much later than Southern Europe and the Mediterranean region did during prehistory. By around 4000 BC, the island was populated by people with a Neolithic culture. This neolithic population had significant ancestry from the earliest farming communities in Anatolia, indicating that a major migration accompanied farming.

The Bronze & Iron Ages and the Beaker people

The beginning of the Bronze Age and the Bell Beaker culture was marked by an even greater population turnover, this time displacing more than 90% of Britain’s neolithic ancestry in the process. This is documented by recent ancient DNA studies which demonstrate that the immigrants had large amounts of Bronze-Age Eurasian Steppe ancestry, associated with the spread of Indo-European languages and the Yamnaya culture.

The Romans

The first Roman invasion of Great Britain was led by Julius Caesar in 55 BC; the second, a year later in 54 BC. The Romans had many supporters among the Celtic tribal leaders, who agreed to pay tribute to Rome in return for Roman protection. The Romans returned in AD 43, led by the Emperor Claudius, this time establishing control, and establishing the province of Britannia.

Initially an oppressive rule, gradually the new leaders gained a firmer hold on their new territory which at one point stretched from the south coast of England to Wales and northwards into Scotland. Hadrian’s Wall (constructed from 122 to 130 AD) and the slightly later Antonine Wall (constructed from 142 to 144 AD) are well known Roman frontiers. However an earlier and less well known Roman frontier was marked by the Gask Ridge system of forts, which was constructed sometime between 70 and 80 AD.

The permanent sites are complemented by a series of large marching camps (large camps date to the 3rd century) from the Scottish Lowlands into Aberdeenshire and Moray. In the first century the Roman Legions also established a chain of forts at Ardoch, Strageath, Inchtuthil, Battledykes (which is unlikely to date from the same period as the Gask sites), Stracathro and Raedykes, taking the Elsick Mounth on the way to Normandykes, before going north to Glenmaillen and Auchinhove. Unconfirmed sites of possible Roman forts have also been found at Bellie, Balnageithand Cawdor.

During the 367 years of Roman occupation of Britain, many settlers were soldiers garrisoned on the mainland. It was with constant contact with Rome and the rest of Romanised Europe through trade and industry that the elite native Britons themselves adopted Roman culture and customs, such as the Latin language, though the majority in the countryside were little affected.

The “Scotti”

During the 5th century, Irish settlers known as the Scotti started raiding north-western Britain from their base in north-east Ireland. After the Roman withdrawal they established the kingdom of Dál Riata, roughly equivalent to Argyll. This migration is traditionally held to be the means by which Primitive Irish was introduced into what is now Scotland. However, it has been posited that the language may already have been spoken in this region for centuries, having developed as part of a larger Goidelic language zone, and that there was little Irish settlement in this period. Similar proposals have been made for areas of western Wales, where an Irish language presence is evident. Others have argued that the traditional narrative of significant migration, particularly in the case of Dál Riata, is likely correct.

“Angles, Saxons & Jutes”

Germanic (Frankish) mercenaries were employed in Gaul by the Roman Empire and it is speculated that in a similar manner, the first Germanic immigrants to Britain arrived at the invitation of the British ruling classes at the end of the Roman period. Though the (probably mythical) landing of Hengist and Horsa in Kent in 449 is traditionally considered to be the start of the Anglo-Saxon migrations, archaeological evidence has shown that significant settlement in East Anglia predated this by nearly half a century.

The key area of large-scale migration was southeastern Britain; in this region, place names of Celtic and Latin origin are extremely few. Genetic and isotope evidence has demonstrated that the settlers included both men and women, many of whom were of a low socioeconomic status, and that migration continued over an extended period, possibly more than two hundred years. The varied dialects spoken by the new arrivals eventually coalesced into Old English, the ancestor of the modern English language.

In the Post-Roman period the traditional division of the Anglo-Saxons into Angles, Saxons and Jutes is first seen in the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum by Bede; however, historical and archaeological research has shown that a wider range of Germanic peoples from Frisia, Lower Saxony, Jutland and possibly southern Sweden moved to Britain during this period. Scholars have stressed that the adoption of specifically Anglian, Saxon and Jutish identities was the result of a later period of ethnogenesis.

Following the settlement period, Anglo-Saxon elites and kingdoms began to emerge; these are traditionally grouped together as the Heptarchy. Their formation has been linked to a second stage of Anglo-Saxon expansion in which the kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria each began periods of conquest of British territory. It is likely that these kingdoms housed significant numbers of Britons, particularly on their western margins. That this was the case is demonstrated by the late seventh century laws of King Ine, which made specific provisions for Britons who lived in Wessex.

The “Vikings”

The earliest date given for a Viking raid of Britain is 789 when, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Portland was attacked. A more exact report dates from 8 June 793, when the cloister at Lindisfarne was pillaged by foreign seafarers. These raiders, whose expeditions extended well into the 9th century, were gradually followed by armies and settlers who brought a new culture and tradition markedly different from that of the prevalent Anglo-Saxon society of southern Britain. The Danelaw, established through the Viking conquest of large parts of the Anglo-Saxon cultural sphere, was formed as a result of the Treaty of Wedmore in the late 9th century, after Alfred the Great had defeated the Viking Guthrum at the Battle of Ethandun. Between 1016 and 1042 England was ruled by Danish kings. Following this, the Anglo-Saxons regained control until 1066.

Though located formally within the Danelaw, counties such as Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, and Essex do not seem to have experienced much Danish settlement, which was more concentrated in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, as demonstrated by toponymic evidence. The Scandinavians who settled along the coast of the Irish sea were mainly of Norwegian origin, though many had arrived via Ireland.

Most of the Vikings arriving in the northern parts of Britain also originated in Norway. Settlement was densest in the Shetland and Orkney islands and Caithness, where Norn, a language descended from Old Norse, was historically spoken, but a Viking presence has also been identified in the Hebrides and the western Scottish Highlands.

The Normans

The Normans were a small but highly elite population who, as revealed by the 1086 Domesday Book, almost entirely replaced the Anglo-Saxon ruling classes in England. While there was no Norman conquest of Scotland, several nobles moved north to Scotland at the invitation of King David I. The Normans were experts at marrying local heiresses, which led to number Norman families coming to prominence in Scotland including the Balliols, the Bruces and the FitzAlans (later known as Stewarts and Stuarts). These three families would be monarchs of Scotland (and from 1603 the whole of Britain) almost continuously from 1292 to 1714.

However, although the Normans formed a powerful elite, they contributed little to the overall genetic makeup of these islands. It has been estimated that they represented only 2% of the population of England, and much less in Scotland.

Flemings

Often overlooked, the later middle ages saw substantial Flemish migration to England, Wales and Scotland. It should be noted that the generic term “Fleming” was used to refer to natives of the Low Countries overall rather than Flanders specifically.

The first wave of Flemings arrived in England following floods in their low-lying homelands during the reign of Henry I. Eventually, the migrants were planted in Pembrokeshire in Wales. According to the Brut y Tywysogyon, the native inhabitants were driven from the area, with the Flemish replacing them. This region, in which Flemish and English were spoken from an early date, came to be known as Little England beyond Wales.

Many of the early Flemish settlers in England were weavers, and established themselves in the larger English towns and cities. In Scotland, Flemish incomers contributed to the burgeoning wool trade in the southeastern part of the country.

In 1778, the minister of Wemyss Parish, Rev. Dr Harry Spens, wrote of his own flock at Buckhaven, ‘… the original inhabitants of Buckhaven were from the Netherlands about the time of Philip II of Spain (died 1598). Their vessel had been stranded on the shore. They proposed to settle and remain. The family of Wemyss gave them permission. They accordingly settled at Buckhaven. By degrees they acquired our language and adopted our dress, and for these threescore years past have had the character of a sober and sensible, an industrious and honest people. The only singularity in their ancient customs that I remember to have heard of was that of a richly ornamented girdle or belt, wore by the brides of good condition and character at their marriage, and then laid aside and given in like manner to the next bride that should be deemed worthy of such an honour. The village consists at present of about 140 families, 60 of which are fishers, the rest land-labourers, weavers and other mechanics.’ (OSA 790–1).

“Some estimates suggest that up to a third of the current Scottish population may have had Flemish ancestors. While this is almost certainly an exaggeration, many Flemish emigrés did settle in Scotland over a 600 year period between the 11th and 17th centuries.” For more information, see the Scotland and the Flemish People project at the University of Saint Andrews.

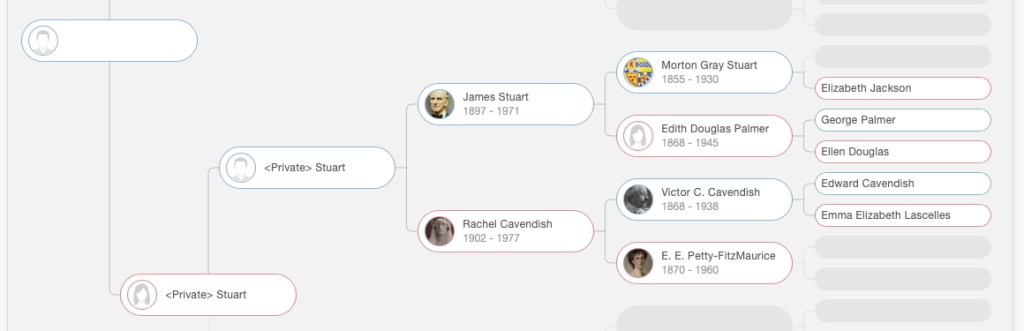

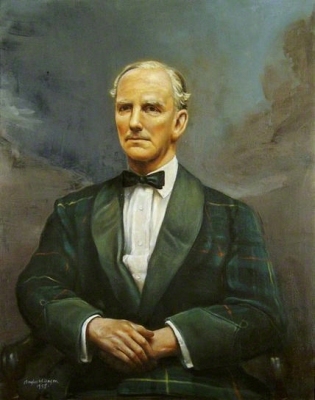

Surprising DNA Matches

Finally, there can also be the odd intriguing and fun DNA match. We were surprised to find a DNA match with a great grandson of James Gray Stuart, 1st Viscount Stuart of Findhorn, CH, MVO, MC*, PC (9 February 1897 – 20 February 1971). He served as Secretary of State for Scotland under Churchill and then Sir Anthony Eden from 1951 to 1957. However, the Viscount is on the match’s maternal side and we suspect strongly that our connection is actually on his paternal side.