DNA testing is a powerful and relatively new way to confirm family relationships with a number of companies offering various services including ethnicity estimates, health and traits and cousin matching.

Collaborations

We are happy to collaborate with DNA matches to attempt to work out where we share common ancestry. (If you are a match on Ancestry DNA you will first need to send an invite to user: iainold)

Reports

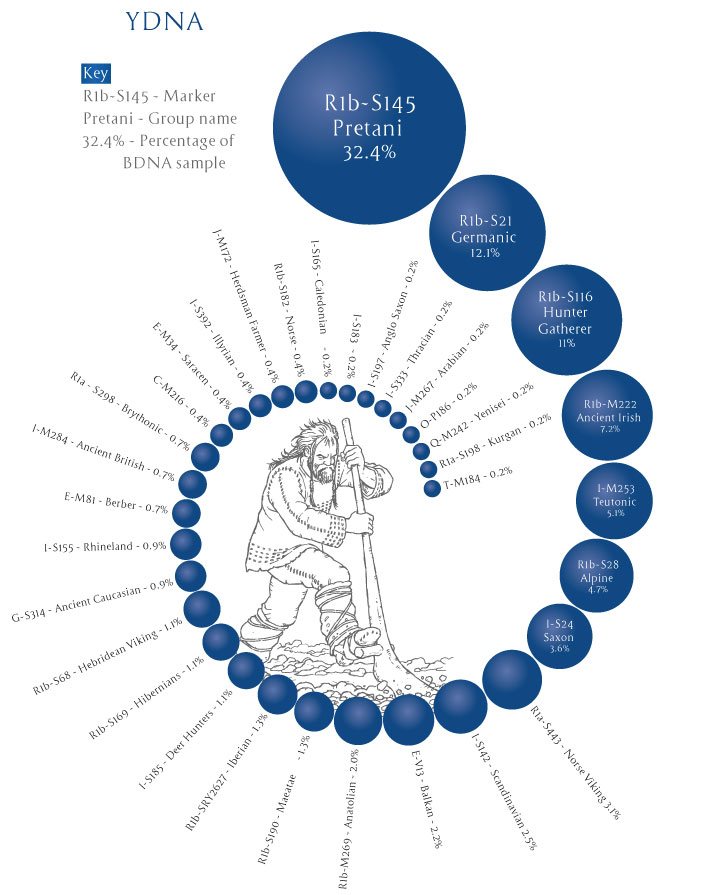

The various companies offer a vast array of different reports, some examples of which are given below.

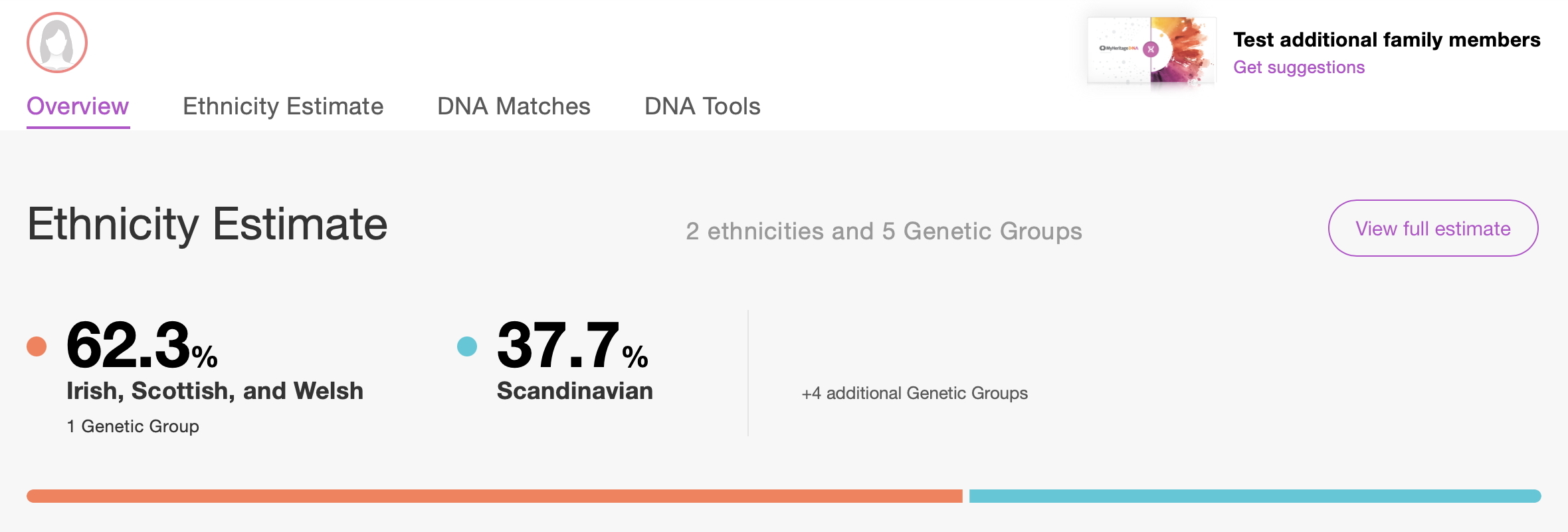

Ethnicity reports

Ethnicity estimates are popular with customers, but are only as accurate as the reference population used by the company in question. In the past, when having Viking ancestry was desirable, it is suggested that in some cases reports were produced that provided the customers with exactly what they wanted. In the case of the male individual above, the ethnicity estimate was not incoherent with the individual’s documentary research which suggested mostly Scottish recent ancestry. However, this is not always the case.

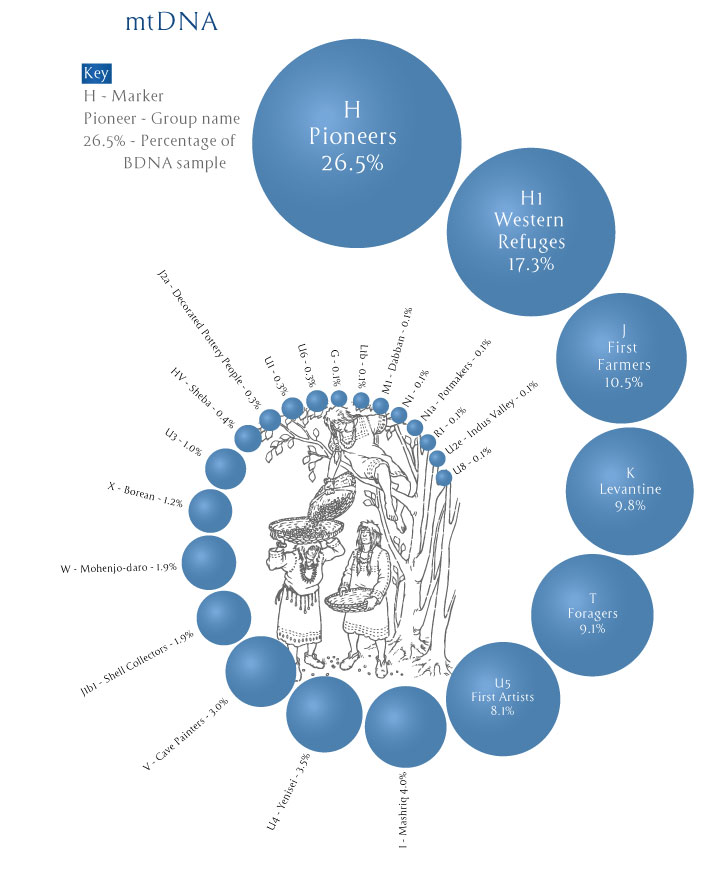

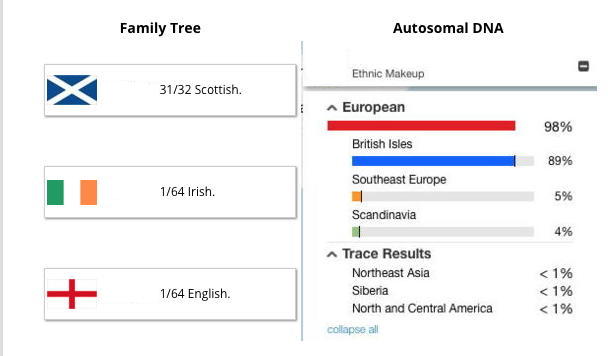

The individual’s mother was tested at several different companies – see detailed results below – with the raw DNA file from FamilyTreeDNA being uploaded to MyHeritage. As can be seen above, the four companies are in general agreement that her genetic heritage is 93.2%-100% British and Irish.

However, attempting to break down this genetic heritage from the British Isles using modern national boundaries produced some vastly different results. In the most extreme example, MyHeritage predicted that she had 46.6% English heritage while Ancestry predicted only 3% (and in Ancestry’s case England was grouped along with Northwestern Europe).

Decades of extensive research had suggested that the individual in question had entirely Scottish ancestry, at least as far back as could be researched using the Old Parish Registers. The exception was her direct maternal line where her great (x2) grandmother was born in England to an Irish mother and a father whose exact identity is yet to be confirmed, but seems likely to have been either Irish or English.

Meanwhile, MyHeritage’s ethnicity estimates for two of the woman’s biological children suggested that they had no English ethnicity whatsoever, not even in the additional minor genetic groups – which are not shown in the summary.

A similar scenario was seen when the BBC’s Watchdog program investigated DNA kits from 23andMe, MyHeritage and Ancestry, stating:

“The results differed for each service.

• MyHeritage told Nikki that her Ethnicity Estimate was 80% English, 20% Iberian (Spain/Portugal).

• 23andMe told Nikki that her Ancestry Composition was 99.9% European (including 61.8% British & Irish, 19.4% French & German) with Trace Ancestry of Broadly Sub-Saharan African.

• Ancestry.co.uk told Nikki that her Ethnicity Estimate was 82% England, Wales and NorthWestern Europe, 15% Ireland and Scotland, 3% Norway.

While there were some similarities, we couldn’t explain why, for example, only MyHeritage identified Iberia in the results; only 23andMe identified Sub-Saharan Africa, and only Ancestry identified Norway.“

Clearly ethnicity estimates are exactly that, estimates, which often need to be taken with a rather large pinch of salt.

Biological ancestors and DNA ancestors

It should be kept in mind that even the most accurate ethnicity test will only be able to supply information about those ancestors from whom we have actually inherited DNA. We inherit approximately half (50%) of our DNA from our father and half (50%) from our mother, in the form of one of the two copies of each of their 22 autosomal chromosomes. (Recombination and crossover means that these chromosomes are not stable and static entities, but possible of evolution and they are made up of a mixture of segments from many different ancestors).

Sex chromosomes are also inherited from each parent – with one X chromosome coming from the mother and either an X chromosome (daughters) or a Y chromosome (sons) coming from the father.

Thus we will inherit on average:

- about 50% of our autosomal DNA from each of our two parents;

- about 25% of our autosomal DNA from each of our four grandparents;

- about 12.5% of our autosomal DNA from each of our eight great grandparents;

- about 6.25% of our autosomal DNA from each of our 16 great (x2) grandparents;

- about 3.125% of our autosomal DNA from each of our 32 great (x3) grandparent and;

- about 1.5625% of our autosomal DNA from each of our 64 great (x4) grandparents.

However, as we go back even further in time and have more and more ancestors, the size of the segments and total amount of DNA inherited from any given distant ancestor will decrease and can vary a great deal.

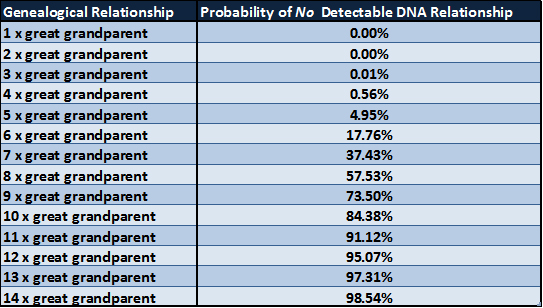

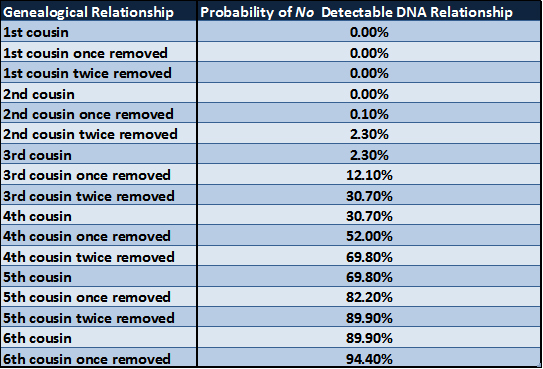

Within a few generations, we will come across some biological ancestors from whom we have inherited no DNA whatsoever. e.g. there is a probability of around 5% that we will share no DNA whatsoever with each of our 128 great (x5) grandparents. Put another way, there could be six great (x5) grandparents from whom we will have inherited no genetic material whatsoever. The number and percentage of ancestors from whom we have inherited no DNA increases sharply as we go further back in time.

The International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) have put together incredibly useful tables (reproduced above) that are derived from Table 1 in the paper The probability that related individuals share some section of genome identical by descent by Kevin P Donnelly, Statistical Laboratory, Cambridge University, Cambridge, England. (Source: Theoretical Population Biology 1983: 23, 34-63). (A copy of the paper is available here.)

It can be seen that by the time we reach great (x10) grandparents there is an 85% chance that we will have inherited no DNA from them. For someone born in 1960 with a 30 year generation time, that would take us back to around 1660 – within the scope of some early Old Parish Registers. And for our great (x14) grandparents, who, in the example above, might have been born around 1480, there is a less than 1.5% chance that we will have inherited any DNA at all from them.

So while many people may claim descent from the likes of William the Conqueror, Charlemagne, Niall of the Nine Hostages, or Pocahontas unless they are a direct male-line descendant of the first three or direct female-line descendant of Pocahontas (who had no daughters) it is unlikely that they will have inherited any DNA from their famous ancestor.

Historical testing companies

It may come as a surprise to some that DNA testing companies have been around for more than 20 years.

oxford ancestors

Oxford Ancestors was a commercial genetic genealogy company launched in April 2000 by Professor Bryan Sykes, a Professor of Human Genetics at the University of Oxford. Oxford Ancestors was set up to meet the anticipated demand for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) tests from members of the public in response to the publication of Sykes’ book The Seven Daughters of Eve (published spring 2001) which claimed to show that almost everyone in Europe was descended on the maternal line from one of seven female ancestors. The “daughters” or clans correspond to the most common mitochondrial DNA haplogroups in Europe. For a list of the clan mother names used by Oxford Ancestors for the mtDNA haplogroups see the ISOGG Wiki list Oxford Ancestors haplogroup nicknames.

Professor Sykes was one of the first researchers to establish a link between the Y chromosome and surnames. His paper “Surnames and the Y chromosome” suggested that the surname Sykes had a single surname founder, even though written sources had predicted multiple origins. A Y chromosome test was also offered to the public on the company’s launch. Oxford Ancestors similarly assign clan names to the Y-DNA haplogroups.

Oxford Ancestors participated in producing the 2001 BBC television documentary, “Blood of the Vikings,” which claimed to show how Y-chromosome DNA testing could reveal Viking ancestry.

Professor Bryan Sykes died on 10th December 2020 and the company ceased trading on 31 December 2020.

ethnoancestry

Ethnoancestry. Ethnoancestry was formed in 2004 and was registered in Scotland and California. The primary goals of the company were to discover new Y-chromosome SNP and STR markers and to develop new tests to help genetic genealogists learn more about their deep ancestry. The company offered Y-STR, Y-SNP and mitochondrial DNA products and was the first to offer commercial testing for the M222 SNP amongst others.

Ethnoancestry’s President and Chief Scientist, was Dr. James F. Wilson, a population geneticist whose publications and credits are familiar to the genetics community. His Ph.D. is from the University of Oxford where his initial studies with David Goldstein led to the popular BBC “Blood of the Vikings” program. Having moved to the University of Edinburgh School of Medicine, he was a key researcher in the International HapMap Project and a founder of ORCADES, a genome- screening project. Jim is also an avid genealogist and a native of the Orkney Islands.

ScotlandsDNA

ScotlandsDNA was launched in November 2011 and ceased trading on 3rd July 2017. It had research at its roots and was born of an innovative project bringing together historical analysis and genetic information from ancestral DNA testing. ScotlandsDNA aimed to provide new insights into the genetic origins of the Scottish and those of Scottish descent. For example, progressive steps had been made in discovering the tremendous diversity of our DNA, from the farthest reaches of Siberia, Africa and Indonesia, to the legacy of the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Danes, and further refining haplogroups into defined subtypes. By taking a test participants not only began their own DNA journey, but also played a valuable role in research into the genetic makeup and origins of a nation. The aim was to write a people’s history of Scotland.

A book written by Alistair Moffat and James Wilson entitled The Scots: A Genetic Journey, which included findings from the company’s tests, was published in 2012.

A second book Britain: A Genetic Journey by Alistair Moffat was published in October 2013.