While researching the Irish descendants of the McAusland Barons, we came across Lt. Nevill Josiah Aymler Coghill, VC, who died at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879 following Sir Henry Bartle Frere, High Commissioner for Southern Africa‘s ill-fated attempt to annex Zululand by invading the kingdom with British forces under the command of Lord Chelmsford.

Coghill was the son of the Hon. Katherine Frances Plunket whose maternal grandmother was Katherine McCausland, daughter of John MacCausland of Strabane (14 May 1735 – November 1804).

John MacCausland of Strabane was the great-great-grandson of Alexander Mccauslane of Rush & Ardstragh, third son of Patrik McCauslane, 21st (in our reckoning) Baron of Caldenoch.

Nevill Josiah Aylmer Coghill VC (25 January 1852 – 22 January 1879) was a British Army officer and recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Family and early life

Born in Drumcondra, Dublin, Coghill was the eldest son of Sir John Joscelyn Coghill (1826–1905), 4th Baronet, JP, DL, of Drumcondra, County Dublin (see Coghill baronets), and his wife, the Hon. Katherine Frances Plunket, daughter of John Plunket, 3rd Baron Plunket. He was a nephew of David Plunket, 1st Baron Rathmore and William Plunket, 4th Baron Plunket. The painter Sir Egerton Coghill, 5th Baronet (who had a son also called Nevill named in his honour) was his younger brother.

Coghill was educated at Haileybury College from 1865 to 1869.[1] In 1876 he set sail with the 24th Regiment of Foot to Cape.

Coghill’s brother named his son, Nevill Coghill after him. Coghill’s nephew became a writer and a member of the Inklings with CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien.[2]

Battle of Isandlwana

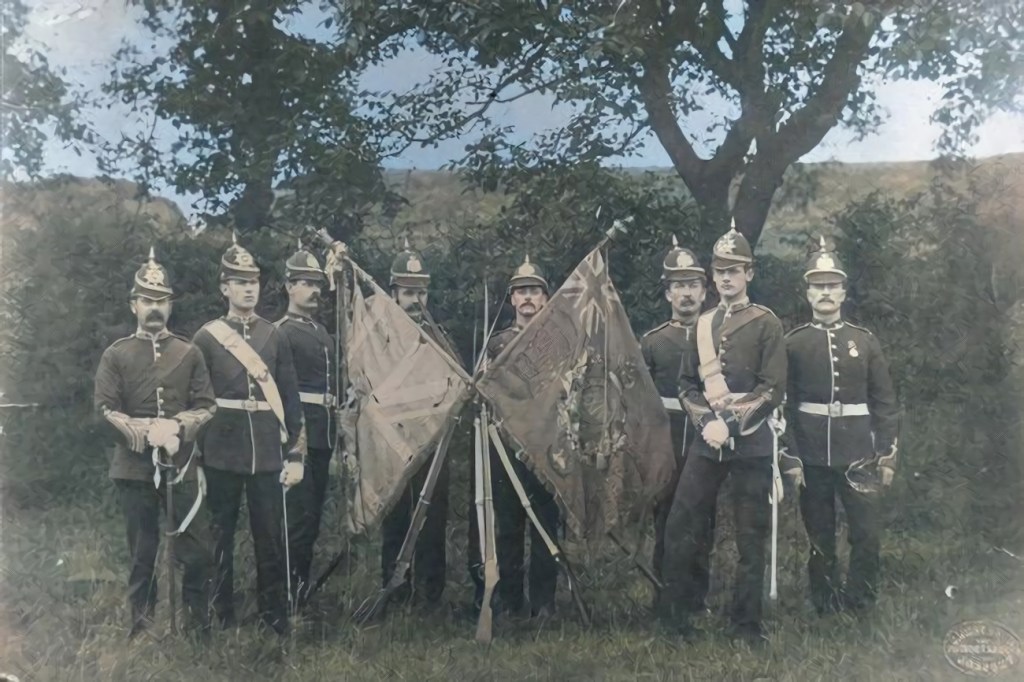

Coghill was twenty-six years old and a lieutenant in the 1st Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot (2nd Warwickshires), British Army, during the Zulu War, when the following deed took place for which he was awarded the VC. He was an orderly officer to Colonel R. T. Glyn, who allegedly regarded him as his favourite officer and the son he never had.

On 22 January 1879, after the disaster of the Battle of Isandhlwana, South Africa, Lieutenant Coghill joined Lieutenant Teignmouth Melvill[3] who was trying to save the Queen’s Colour of the Regiment. They were pursued by Zulu warriors, and while crossing the swollen River Buffalo, Lieutenant Coghill (despite his injured knee) went to the rescue of his brother officer, who had lost his horse and was in great danger.

Although Coghill’s horse was shot by a Zulu warrior, the valiant soldier swam on to rescue Melvill. After some time, the Colour was swept from their grasp and floated down the bank. After reaching the bank, the two men were eventually overtaken by the Zulu warriors and, following a short struggle, both were killed.[4][5] Lieutenant Walter Higginson, who was persuaded to escape, heard and witnessed their final actions when they fought to the last.

Source: Memories of Forty-Eight Years’ Service Page 12 by General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (1 January 1925).

The Colour was retrieved from the river ten days later by a mounted party under Major Wilsone Black.[6]

Legacy and award of Victoria Cross

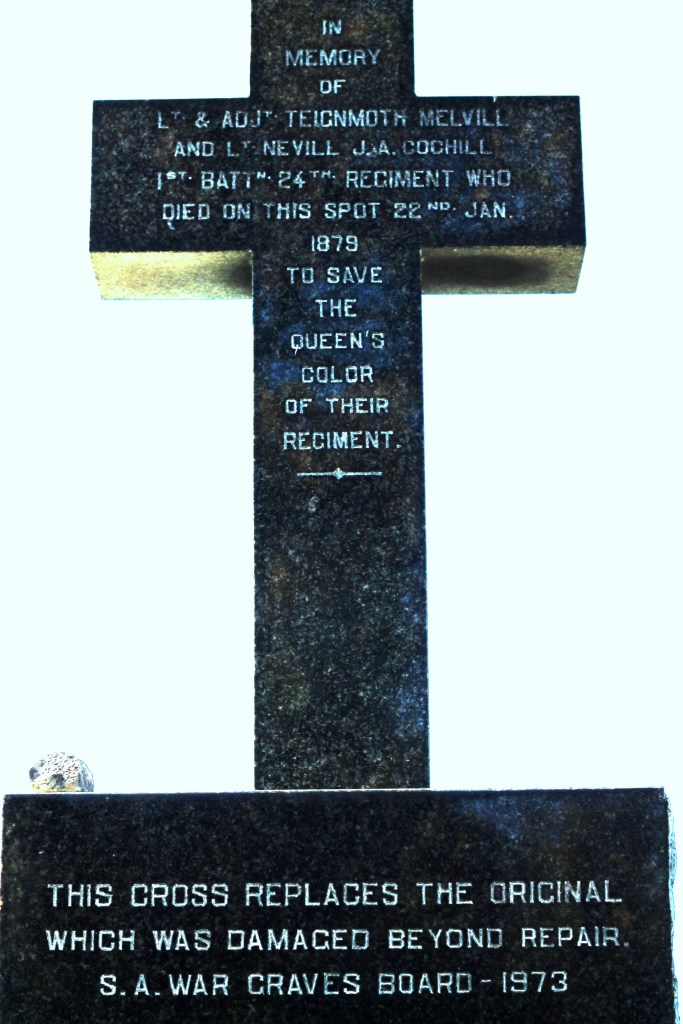

CC BY-SA 3.0 Location: 28° 22′ 59″ S, 30° 34′ 59″ E

Two weeks after the battle, Coghill and Melvill’s bodies were found by a search party[7] and both buried at Fugitive’s Drift.[8]Major-General Dillon informed Coghill’s father in a letter, that had it not been for the valour of his son, the Colour would have fallen to Zulu hands. Coghill’s father donated his son’s trophies including a Zulu shield to the Museum of Science and Art, now the National Museum of Ireland.[9] Coghill and Melvill were amongst the first soldiers to receive the VC posthumously in 1907. Initially The London Gazette mentioned that had they survived they would have been awarded the VC.[10]

Chromolithograph after Alphonse de Neuville, 1881.

Lieutenant Nevill Coghill and Lieutenant Teignmouth Melvill of the 1st Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot, were killed attempting to defend their unit’s Queen’s Colour (rather than the Regimental Colour as depicted here) in the aftermath of the British defeat at Isandlwana on 22 January 1879. They were caught by the Zulus as they attempted to carry the colour across the Buffalo River. Despite their brave efforts they were eventually overwhelmed. Although 23 Victoria Crosses were won during the Zulu War (1879), Coghill and his fellow officer had to wait until January 1907 to receive their posthumous awards.

A few months after the Battle of Isandlwana, a French battle artist, Alphonse de Neuville painted Coghill and Melvill’s actions when they were pursued by Zulu warriors.[11]

The attempted escape of Melvill and Nevill Coghill was depicted in the 1918 silent film Symbol of Sacrifice.[12] Coghill was portrayed by Christopher Cazenove in the 1979 film Zulu Dawn as a polite and humorous officer.[13][14][15] In the film, he is friends with Melvill; their heroic actions when they crossed the Buffalo River in a desperate attempt to return the Queen’s Colour back to Natal was depicted in the film.

Coghill’s great-great-great grand-niece, Jane Mann, in 2014, passed a painting (of her ancestor and Melvill pursued by Zulus) by contemporary military artist Jason Askew to the Victoria Cross Museum.[16]

Lieutenants Melvill and Coghill were among the first British soldiers to be posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, and both these medals now form part of the Museum’s permanent collection.

The Colour which Coghill and Melvill tried to save was recovered and is on display at Brecon Cathedral in remembrance of their valour as well as other soldiers killed during the battle. Coghill’s Victoria Cross is permanently displayed at the Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh in Brecon, Powys, Wales.[8] At Haileybury College, a leadership programme for pupils in Removes is named in his honour.[8]

Saving The Colours (Full) | Zulu Dawn | HD.