We are very grateful to Dr Yulia Anya Guthrie, one of several contributors to this blog, for the following guest article regarding the royal imagery used in Peter McAuslane’s arms.

Heraldry

The Encyclopaedia Britannica noted that: “Heraldry originated when most people were illiterate but could easily recognise a bold, striking, and simple design. The use of heraldry in medieval warfare enabled combatants to distinguish one mail-clad knight from another and thus to distinguish between friend and foe. Thus, simplicity was the principal characteristic of medieval heraldry. In the tournament there was a more elaborate form of heraldic design. When heraldry was no longer used on body armour and heraldic devices had become a part of civilian life, intricate designs evolved with esoteric significance utterly at variance with heraldry’s original purpose. In modern times heraldry has often been regarded as mysterious and a matter for experts only. Indeed, over the centuries its language has become intricate and pedantic. Such intricacy appears ridiculous when it is remembered that in the earlier periods swift recognition of a coat of arms or badge could mean the difference between safety and death, and some medieval battles were lost through a mistake over the similarity of two devices of opposing sides.“

“Like all other human creations, heraldic art has reflected the changes of fashion. As heraldry advanced from its utilitarian usages, its artistic quality declined. In the 18th century, for example, heraldry described new arms in an absurdly obtuse manner and rendered them in an overly intricate style. Much of the heraldic art of the 17th to 19th centuries has earned that period the designation “the Decadence.” It was not until the 20th century that heraldic art recovered a feeling for aesthetic beauty. There are still, however, a few drawings of poor quality emanating from official sources.”

The four McAusland Grants of Arms between 1863 and 1965

The Arms Referred to in the McAusland Arms

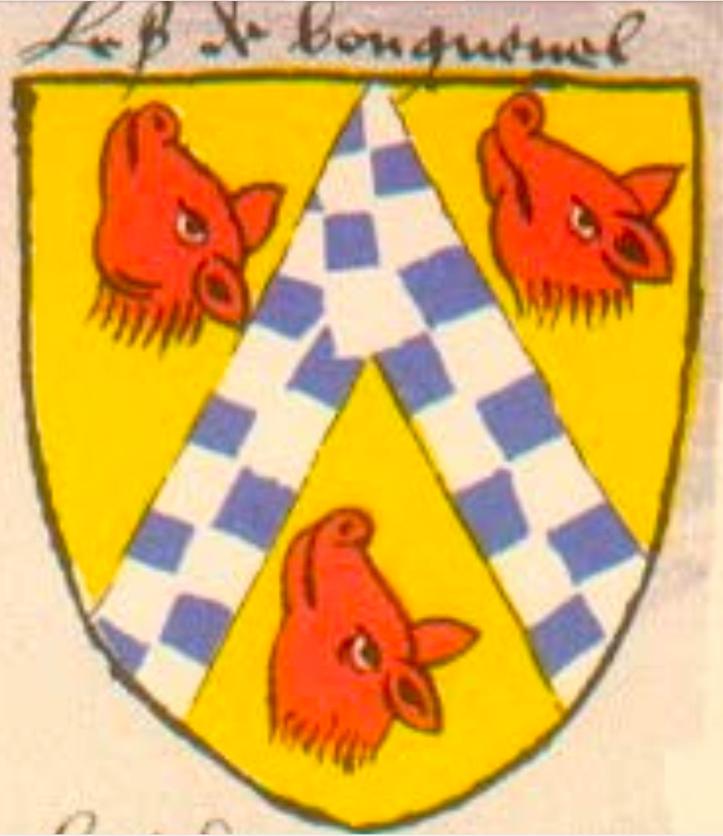

In the Scottish section of the French Armorial de Berry, published around 1445, the arms of Buchanan (Le sire de bouguenal) are Or (gold/yellow), chevron checky of Azure (Blue) and Argent (silver/white), and the three boars heads erased and erect of Gules (red).

However, ten years later, in 1455, The Scots Roll describes a completely different set of arms for the Buchanan (Bachanane) chief, which now clearly resembled those of the royal arms of Scotland (compare the two images below).

How can these two different version be reconciled? It is thought that three events led to a total transformation in the Buchanan Chief’s arms. These events were:

Firstly in 1421, when Sir Alexander (McAuslane) of Buchanan, son of Sir Walter Buchanan of that Ilk, 11th Chief of Clan Buchanan, killed the Duke of Clarence (second son of King Henry IV of England) at the Battle of Baugé in France.

Secondly, the 1425 execution, ordered by King James I of Scotland, of his first-cousin, Murdoch Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany, along with Murdoch’s two older sons, and his father-in-law the Earl of Lennox, for treason.

Thirdly, the 1443 marriage of Sir Walter Buchanan of that Ilk, 12th Chief of Clan Buchanan and his second wife, Lady Isobel Stewart, a daughter of the executed Murdoch Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany.

It seems likely that the fess chequy azure and argent in the 1445 version of the Buchanan arms was a very recent addition that made a clear statement of the connection of the Buchanan chiefly line to that of the Scottish royal Stewart line following the 1443 marriage of Sir Walter Buchanan of that Ilk, 12th Chief of Clan Buchanan, and his second wife, Lady Isobel Stewart, daughter of Murdoch Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany and Isobel Countess of Lennox suo jure (in her own right).

This second marriage produced no children, and it seems possible that this radical change to adopt a clear variant of the royal arms of Scotland as the Buchanan chief’s arms was a dramatic and rather unsubtle way of reminding people of the Buchanan’s connections, even if it had not resulted in any heirs, to the Scottish kings, via the Albany branch of the Stewarts, who had been so close to inheriting the Scots crown and who, as Regents and Governors for Kings Robert II, Robert III and James I, were the de facto rulers of Scotland almost continuously between 1388 and 1424. The only exception was when David, Duke of Rothesay was appointed by parliament as “Lieutenant” of the kingdom on behalf his father, King Robert III, in January 1399 until his arrest in late February 1402 by his uncle, Robert 1st Duke of Albany.

Isobel Stewart’s father, Murdoch Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany, succeeded his father to become Governor of Scotland while King James I was still held captive in England, from the death of his formidable father, Robert Stewart, 1st Duke of Albany in 1420. However, King James I was finally released, after an enormous ransom of 60,000 marks was agreed at Durham on 28 March 1424. Then King then proceeded to Melrose Abbey, and on 5th April 1424, he met his cousin Murdoch, 2nd Duke of Albany who was obliged to submit his Seal of Office as Governor of Scotland.

The Albany Stewarts had almost certainly been complicit in the death of King James’ elder brother, David, Duke of Rothesay, who had been arrested by his uncle, Robert, 1st Duke of Albany, and who had subsequently died, allegedly starved to death, at their castle of Falkland. From then on, only Robert’s elderly and frail brother John (who reigned as King Robert III) and his young son James, Duke of Rothesay, stood between the Albany Stewarts and the Crown of Scots. During the winter of 1405–6, the decision was made to send James to the safety France to put him out of Albany’s reach. After a failed attempt by the Douglases to prevent this, James escaped to the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth. After several weeks, they boarded the Danzig ship Maryenknyght, which was bound for France. However, on 22th March 1406, the ship was captured by the English. King Robert III was at Rothesay Castle when he heard that his only son and heir had been captured. On 4th April 1406, King Robert III died and only ten days into his 18 year long captivity, James, Duke of Rothesay became King James I.

The Albany Stewarts, Robert and later his son Murdoch, had been content for James to remain as a captive in France as this allowed them to rule Scotland as kings in all but name. Perhaps unsurprisingly, after his 18 year captivity, when King James I felt strong enough, he arrested his cousin Murdoch and his family. On 18 May 1425, at a parliament in the presence of the King at Stirling Castle, Murdoch Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany was tried in a court attended by seven earls and fourteen other nobles – including Murdoch of Albany’s half-uncle Walter Stewart Earl of Atholl, first cousin Alexander Stewart, Earl of Mar, first cousins once removed Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Douglas, and Alexander, Earl of Ross & Lord of the Isles. Murdoch, 2nd Duke of Albany, his sons Walter and Alexander, and his father-in-law, Duncan, Earl of Lennox, were found to be guilty of treason. They were attainted, their peerage titles were forfeited and they were beheaded at “Heading Hill” in Stirling.

In these circumstances, the 1443 marriage of Sir Walter Buchanan of that Ilk, 12th Chief of Clan Buchanan, and his second wife, Lady Isobel Stewart could be seen as both dangerous, linking the Buchanans to the forfeited Albany Stewarts, but also advantageous, given their royal connections.

Summary

The 1863 grant of arms to Robert McCasland of Newlandmuir is a clear homage to the McAuslands being related to Clan Buchanan being the Black Buchanan Lion on a gold field, with the addition of two stars, a sword and arrowhead – the sword perhaps being a reference to the fact that he was a Captain (later Major) in Her Majesty’s Royal Regiment of Lanarkshire Militia.

Meanwhile, the three later grants to members of the McAuslands of Prestilloch line – in 1891 to James McAuslane; in 1945 to his first cousin, once removed, Peter McAuslane; and in 1963 to Peter’s daughter “Baroness” Helen McAuslane “of Caldenoch” – are rather different. They contain the Black Buchanan Lion on a gold field topped with the blue and white chequy from the Stewart arms. This is clearly a reference to the recent members of the Prestilloch line of McAuslands being descended from Isabel Stewart, daughter of Alexander Stewart, 4th Laird of Ballachullish, and via him back to King Robert II, the first Stewart King of Scots.

The well-known motto of Clan Gregor is ‘S Rioghal mo dhream (Royal is my race), but to those few who understand heraldic symbology, the McAuslane arms also cry out:

“Look at Me! I am a descendant of the Royal House of Stewart!”.

Julie Guthrie, 5th January 2024

To Prince Michael in The Prisoner of Zenda:

There are moments in your presence, Your Highness, when I feel myself an amateur.