Dunbar has been inhabited for at least 6,000 years.

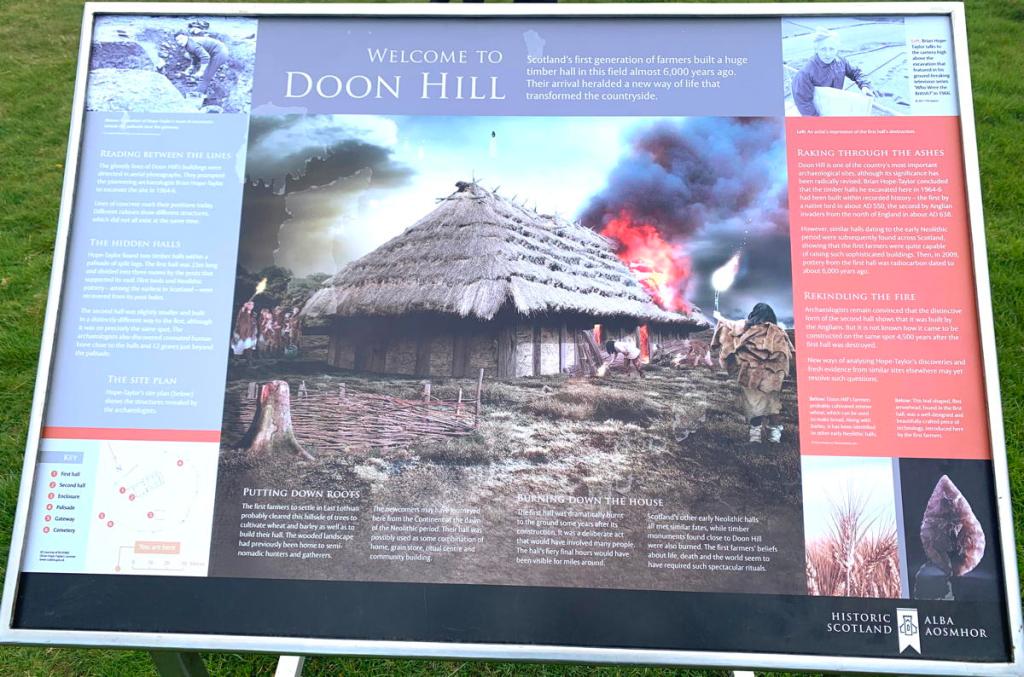

Doon Hill Neolithic Fort

Doon Hill, which is located about 500 metres east of Spott, and 3 kilometres south of Dunbar was the site of a pair of wooden halls which were first excavated between 1964 and 1966 by Brian Hope-Taylor. The later hall is believed to have been built by Anglo-Saxons around the year 640 while the older hall was originally thought to have been built by pre-Anglo-Saxon Britons. However, recent radiocarbon dating has shown the first hall to have been considerably older, dating to around 4000 BCE in the neolithic period.

Dunbar in the Bronze and Iron Ages

Human remains from the later Bronze Age/early Iron Age (800–540 BC) have been found at Dunbar, while the remains of an Iron Age promontory fort was found at Castle Park.

The Votadini and the Romans

Dunbar was a principal centre of the people known to the Romans as Votadini and may have grown in importance when the great hillfort of Traprain Law was abandoned at the end of the 5th century AD.

Annexed by the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria

Dunbar was subsumed into Anglian Northumbria as that kingdom expanded in the 6th century and is believed to be synonymous with the Dynbaer of Eddius around 680, the first time that it appears in the written record.

Part of the Kingdom of the Scotland

Dunbar was burnt by Kenneth MacAlpin in the 9th century. Scottish control was consolidated in the next century and when Lothian was ceded to Malcolm II after the battle of Carham in 1018, Dunbar was finally an acknowledged as part of Scotland.

The town became successively a Baronial Burgh and was created a Royal Burgh in 1370 by King David II. The town grew slowly under the shadow of the great Castle of the Earls of Dunbar which was slighted (deliberately ruined) in 1568 after Mary Queen of Scots was abducted and taken there by her third husband the Earl of Bothwell.

Two major battles were fought at Doon Hill, by Dunbar, in 1296 and 1650. The first Battle of Dunbar was a cavalry encounter fought by the village of Spott and resulted in a decisive victory for the English. The second was fought during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms between a Scottish Covenanter army and English Parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell. The Scots were routed, leading to the overthrow of the monarchy and the occupation of Scotland.

A permanent military presence was established in the town with the completion of Castle Park Barracks in 1855 and Dunbar remained a garrison town for a full 100 years until the barracks were decommissioned in 1955.

Over the years, a number of notable people have visited Dunbar including:

Mary, Queen of Scots, 1566 & 1567

oil on panel, inscribed 1578. Used with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery.

Mary, Queen of Scots connection with Dunbar is very extremely powerful as Dunbar castle is associated with some of the most dramatic periods in what was a very dramatic life of the woman who was Queen regnant of Scotland, Queen consort of France, and who, had she lived, could also have been Queen regnant of England. On the 9th of March 1566, the Lords of the Congregation murdered Mary’s private secretary, David Rizzio. Even more shocking was that the murder was carried out in the presence of the heavily pregnant Queen at Holyrood Palace, with Mary’s husband Lord Darnley as one of the conspirators. However, Mary held her nerve and a mere two days after the murder she managed to detach Darnley from the cabal and escape her imprisonment. However Lord Darnley feared the consequences of his betrayal of the Lords of the Congregation and rode on ahead showing little concern for Mary’s welfare. The pregnant Queen’s flight by horse to Dunbar castle took five hours. The unborn child would soon become James VI of Scotland, and some believe the shock experienced by his mother may have contributed to James’ at times nervous character. The Queen was able to rally her supporters at Dunbar and she made a triumphant return to Edinburgh a week later with the murderers fled to safety in Elizabeth Tudor’s England. (Although Mary was Elizabeth’s first cousin once removed, perhaps more importantly, Catholic Mary was Protestant’s Elizabeth’s heir presumptive and therefore seen as a danger rather than a relative and ally.) Mary felt secure enough to undertake a Progress in the autumn of 1566, and Dunbar Castle was one of the places visited.

A year later, following the murder of Mary’s second husband Darnley at Kirk o’ Field, James Hepburn 4th Earl of Bothwell abducted Mary on 24th April 1567 while the Queen was returning from Stirling Castle where she had visited her infant son, Prince James, later King James VI. Bothwell took her to Dunbar Castle, where he is said to have raped the Queen in order to force her into a situation where she would have no choice but to marry him in order to save her honour. It was at Dunbar Castle that the Queen is said to have miscarried the twins who were fathered by Bothwell. Whatever the motivation, Queen Mary created Bothwell Duke of Orkney and Marquis of Fife on the 12th May and the couple were married on the 15th at Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

On 11th of June 1567, Bothwell and Mary were at Borthwick Castle when they were surrounded by one thousand horsed troops led by Morton, Mar, Hume, and Lindsay. Bothwell escaped and fled to Dunbar Castle, where Mary was later able to join him. They mustered troops which confronted the nobles at Carberry Hill on 15th June 1567, resulting not in the reinstatement of Mary, but in her forced abdication and imprisonment for almost a year at Lochleven Castle.

Oliver Cromwell, 1650

Much has been written about Oliver Cromwell’s dramatic defeat of the Scots at the second Battle of Dunbar on 3rd September 1650, shortly after his successful Irish campaign and exactly a year to the day before the final defeat of the Royalist army at Worcester. Cromwell is still very much a marmite figure, worshipped by some and seen as a tyrant and war criminal by many others as detailed in the following extract:

“There are historic links to my constituency in this institution, and not just through those who have been elected Members. When I first arrived here last month, I came across a statue of Oliver Cromwell, who is well known in my constituency, in the town of Dunbar. He is not viewed as the Lord Protector; far from it. He may not have been as brutal there as he was at Drogheda, but people still suffered at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, when his English army killed thousands of Scottish soldiers and captured thousands more. Those who were captured were marched south, with many dying en route. They were taken to Durham cathedral, where thankfully a memorial now recognises what they suffered. Many died in incarceration there. Of those who were released thereafter, some were given by the Lord Protector to the army of France. Others were sent to do drainage work in the area of the Wash in southern England. Others still were transported to Barbados and to the Americas.

“But some good did come from this, because in 1657, seven years after serving their penal servitude, some of those Scottish soldiers banded together to form the Scots Charitable Society of what is now Boston, which is argued to be the one of the oldest such charitable organisations not just in the United States but in the western hemisphere. They keep contacts with the community in Dunbar, as indeed did the Scottish Prisoners of War Society—because such an organisation does exist, with many American members, and they had a re-enactment of the battle last year.“

From the Maiden Speech of Kenny MacAskill, Member of Parliament for East Lothian, 15th January 2020.

General Sir John Cope, 1745

“Sir John Cope trode the north right far,

Yet ne’er a rebel he cam naur,

Until he landed at Dunbar

Right early in a morning.“

Sir John Cope (July 1688 – 28 July 1760) was the Commander in Chief of the Hanoverian forces in Scotland in 1745 and is now mostly remembered for his defeat at the Battle of Prestonpans, which was commemorated by the tune “Hey, Johnnie Cope, Are Ye Waking Yet?“. Cope was arguably the last man to invade the town of Dunbar at the head of a hostile army – at least from the Jacobite, if perhaps not the Hanoverian point of view!

Image: Copyright The Battle of Prestonpans [1745] Heritage Trust.

Image: Copyright The Battle of Prestonpans [1745] Heritage Trust.

Queen Victoria, 1878

Queen Victoria was the great (x3) granddaughter of Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover. Though both England and Scotland had recognised Anne Stuart as their legitimate monarch, only the Parliament of England had nominated Georg’s mother, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, as the heir presumptive. The Parliament of Scotland (the Estates) had not formally settled the succession question for the Scottish throne and the contested succession of Georg Ludwig (Electress Sophia having predeceased Queen Anne) led to many years of military conflict between those who supported the House of Hanover and the Jacobites.

Although the Stuarts continued to retain significant support, when the last of the Stuart direct line, Henry Benedict died childless in 1807, the Jacobite claim was then notionally inherited by Henry’s nearest relative (a second cousin, twice removed), and then passed through a number of European royal and ducal families. Although the line of succession can continue to be traced, none of these subsequent heirs ever claimed the British throne, or the crowns of England, Scotland, or Ireland, leaving Queen Victoria, and her successors secure on their thrones.

Queen Victoria spent several days in and around Dunbar in 1878 when she stayed with the Duke and Duchess of Roxburgh at Broxmouth. She recorded the visit in her diary, and was seemingly, at least initially, not amused!

“Saturday, August 24, 1878; Morning. Had not a very good night, and was suffering from a stiff shoulder. It was a very wet morning at Dunbar, which we reached at a quarter to nine where the station was very prettily decorated, were the Duke and Duchess of Roxburghe, the Grant-Sutties, the Provost, and Lord Haddington, Lord Lieutenant of the county.

“We got into one of my closed landaus – Beatrice, Leopold, the Duchess of Roxburghe and I – the others following, and drove through a small portion of Dunbar, Lord Haddington riding to Broxmouth, about a mile and a quarter from Dunbar. People all along the road, arches and decorations on the few cottages, and very loyal greetings.

“The park is fine with noble trees and avenues. It is only a quarter mile from the sea, which we could see dimly as we drove from Dunbar.”

And after a couple of days to recover from her journey, the Queen wrote: “Monday, August 26th, 1878, Mid-Morning, Broxmouth Park. Walked out at half past ten with Beatrice and the Duchess to the very fine kitchen garden, and to the splendid hothouse, where they have magnificent grapes. The peaches are also beautiful.

“From here we walked again along the burn side to the sea. The duchess’s pretty and very amiable collie (smaller than Noble, but with a very handsome head), Rex, going with us. We looked at the Lord Warden (Captain Freemantle), which arrived yesterday from Spithead, where we saw her in the Fleet. She had been guardship last year.

“There is a pretty view from this walk to the sea over a small lake, with trees beyond which is Dunbar seen in the distance. Then I sat out in the garden and wrote. After that, when Beatrice returned from a walk near the sea with the Duchess, I went to look at the gravestone of Sir William Douglas, which is quite concealed amongst the bushes near the lawn.“

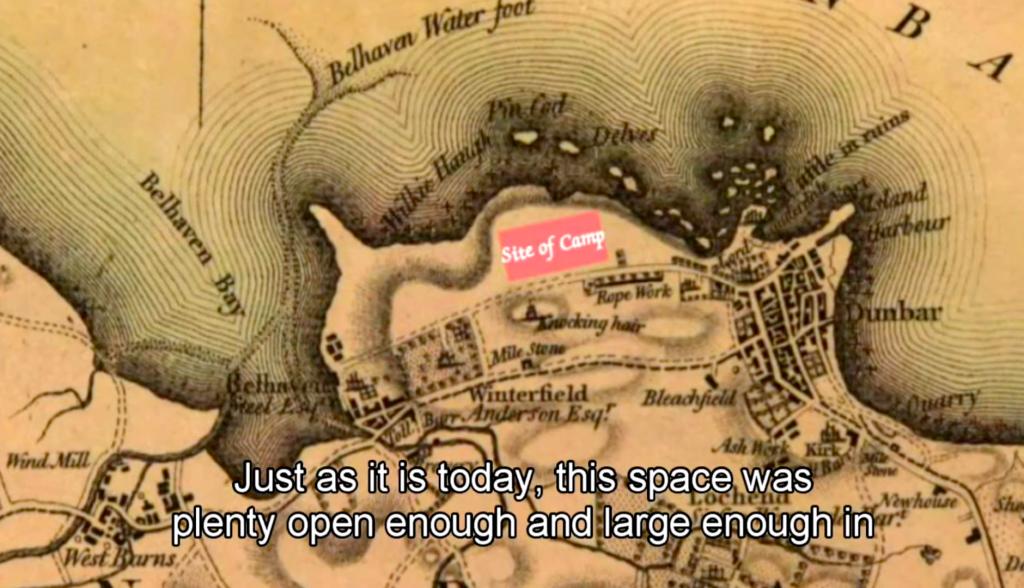

“The Battle of Dunbar took place (September 3rd, 1650) close to Broxmouth, and Sir Walter Scott says Cromwell’s camp was in the park; but this is doubtful, as it is described as on the north of the Broxburn. Leslie’s camp was on the Doune[Doon] hill, conspicuous for miles around.

“When the Scottish army left their strong positions on the hill, they came to the low ground near the park wall. Cromwell is said to have stood on the hillock, where the tower in the grounds has been built, and the battle must have been fought close to the present park gate. I afterwards planted a deodar (Himalayan cedar) on the lawn in the presence of the Duke and Duchess.”

Rikki Fulton & Jack Milroy, 1969

The old swimming pool at Dunbar no longer exists, but in the days before foreign holidays became widely available, Dunbar open air pool was a real visitor attraction with events hosted by big Scottish stars such as Francie and Josie (Jack Milroy and Rikki Fulton).

Sir Peter Heatley, 1979

Front row, left to right: Phyllis, Susan Jamieson, Elaine Gray, ?, Elaine Kerr.

Colourised version of an old black and white photo in the author’s possession – the T shirts were actually red.

Sir Peter Heatley formally re-opened Dunbar Swimming Pool in 1979 when its management was taken over from the council by the local trader’s association. Sir Peter Heatly, CBEDL (09 June 1924 – 17 September 2015) was a Scottish diver and Chairman of the Commonwealth Games Federation. He competed in the 3 metre springboard and 10 metre platform at the 1948 and 1952 Olympics, at the 1950, 1954 and 1958 British Empire Games, and at the 1954 European Championships. He won five British Empire Games medals and one European medal, while his best Olympic result was fifth place in 1948. Heatly was knighted in 1990, before being inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame in 2002, the Scottish Swimming Hall of Fame in 2010 and the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 2016.

Ally McLeod

Well-kent faces have been seen in Dunbar for many years. At the town’s renowned Battleblent Hotel, run by Jim and Faye Ferguson and their sons Martin and Kevin (pictured on left) visitors might have been served a pint by Scotland Football Manager, Ally McLeod.

Kylie Minogue

Some like Caroline Smith (now Williams) may have been surprised to encounter Neighbours star and singer Kylie Minogue at the Battleblent.

The late Queen Elizabeth, 1986

Magnum Magnusson, 1997

David Hayman, 2015

Famous faces can still be seen visiting Dunbar: David Hayman was in the High Street by John Muir’s Statue for an episode of Hayman’s Way, his tribute to Weir’s Way, in 2015.

Judy Murray, 2015

In 2015, Judy Murray, the mother of professional tennis players Jamie and Sir Andy Murray started the day at Dunbar Primary School and kicked off the first of nine Tennis on the Road sessions as part of a four day roadshow across East Lothian.

The Duke of Kent, 2019

Walkers in Winterfield Park might have bumped into the Queen’s cousin, the Duke of Kent in 2019.

Susan Calman, 2020

Michael Portillo, 2021

And most recently Michael Portillo alighted at Dunbar station before visiting Siccar Point in Berwickshire, famous in the history of geology for Hutton’s Unconformity, found in 1788, which James Hutton regarded as conclusive proof of his uniformitarian theory of geological development.

Other notable people with Dunbar Connections

Although no longer the massively popular holiday destination that it once was, with its excellent transport links to Edinburgh and coastal location, Dunbar is one of Scotland’s fastest growing towns. New, and old residents however might be surprised at some of the famous past residents of the town, who include:

- Saint Wilfrid, (c. 633 – 709 or 710). Seventh to early eighth century English bishop and saint was imprisoned for a time in Dunbar.

- Saint Cuthbert, (c. 634 – 20 March 687). Early saint and evangelist of the Northumbrian church, Bishop of Lindisfarne, at a time when Northumbria was a leader in promoting and spreading the message of Christianity in a British and wider European context and, he was, according to some authors, born in and initially brought up in Dunbar to a local noble family, before being fostered in the Melrose area with a related or allied family as per the traditions of his class and time.

- Black Agnes, (c. 1312 – 1369). Countess of Dunbar, and daughter of Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, nephew and companion-in-arms of Robert the Bruce, and Moray’s wife, Isabel Stewart, herself a daughter of John Stewart of Bonkyll Renowned for her heroic defence of Dunbar Castle against an English siege led by William Montagu, 1st Earl of Salisbury, which began on 13 January 1338 and ended on 10 June the same year during the Second War of Scottish Independence from 1331 to 1341.

- Joan Beaufort, (c. 1404 – 15 July 1445). Queen of Scots, wife of King James I of Scotland, who served as the Regent of Scotland in the immediate aftermath of his death and during the minority of her son James II of Scotland, before being engulfed in a power struggle with members of the nobility. In desperation she took refuge in Dunbar Castle where she was subsequently besieged by her opponents, in which place and circumstances she died in the year 1445.

- Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany, (c. 1454 – 07 August 1485). Second son of King James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders, was Duke of Albany, Earl of March, Lord of Annandale and Isle of Man and the Warden of the Marches, which altogether gave him an impressive power base in the east and west borders, centred on Dunbar Castle which he owned and lived in. He attempted to seize control of Scotland from his brother King James III of Scotland, but was ultimately unsuccessful.

- John Stewart, Duke of Albany, (08 July 1482 – 02 July 1536). de facto ruler of Scotland and important soldier, diplomat and politician in a Scottish and continental European context, was the only son of the above Duke of Albany, and managed where his father had failed and became Regent of Scotland, while he also became Count of Auvergne and Lauraguais in France and, lastly, inherited from his father the position of Earl of March, which allowed him to likewise use Dunbar Castle as his centre of power in Scotland.

- James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, (c. 1534 – 14 April 1578). Notorious third and last husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, and owner of Dunbar Castle.

- Alexander Dow, (1735/6, Perthshire, Scotland – 31 July 1779, Bhagalpur). Influential Orientalist, author and British East India Company army officer and resident and educated in Dunbar for part of his boyhood.

- Robert Wilson (engineer), (10 September 1803 – 28 July 1882). One of the inventors of the ship’s propeller, born and bred in Dunbar from a local family.

- Sergeant John Penn (1820–86), a survivor of the Charge of the Light Brigade. Settled in Dunbar.

- Sir Anthony Home, VC KCB, (30 November 1826 – 10 August 1914) British soldier who was notable as a recipient of the Victoria Cross and the eventual achievement of the rank of Surgeon-General of the British Armed Forces, born and bred in Dunbar from a local family.

- John Muir, (21 April 1838 – 24 December 1914). Important conservationist, geologist, environmental philosopher and pacifist; one of the founders of the United States system of National Parks and Sierra Club. Born in Dunbar.

- Walter Runciman, 1st Baron Runciman, (06 July 1847 – 13 August 1937). Major shipowner and maverick Liberal politician, born in Dunbar to parents from Dunbar where Runciman Court is named after him.

- General Sir Reginald Wingate, (25 June 1861 – 29 January 1953). 1st Baronet, GCB, GCVO, GBE, KCMG, DSO, TD, army officer and colonial governor, ‘the maker of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan‘, Governor-General of the Sudan (1899–1916), British High Commissioner in Egypt (1917–1919), commander of military operations in the Hedjaz (1916–1919), for many years the senior general of the British army, long-time resident in Dunbar.

- Jack Hobens (1880 – 1944) was a Scottish-American professional golfer.

- Dr James Wyllie Gregor FRSE (1900–1980). Botanist, born in Dunbar.

- William Alexander Bain (20 August 1905 – 24 August 1971). Pharmacologist, best known for his early work with antihistamine drugs.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper, (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003). Renowned English historian. He boarded at Belhaven Hill School.

- Maria Lyle, (born 14 February 2000). Para-sprinter, won medals at both the Commonwealth and Olympic Games.