The Guthries and the Mitfords

Mention the Mitford sisters to a millennial and you will most likely receive a blank stare, but in their day the six daughters of David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford, 2nd Baron Redesdale and his wife Sydney Bowles were as notorious as they were famous for their stylish and controversial lives, and for their public political divisions between communism and fascism. Nancy and Jessica became well-known writers: Nancy wrote The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, and Jessica The American Way of Death (1963). Deborah married Andrew Cavendish, the future 11th Duke of Devonshire, managed Chatsworth, one of the most successful stately homes in England and was also a prolific author.

Jessica and Deborah married nephews of prime ministers Winston Churchill and Harold Macmillan, respectively. Deborah and Diana both married wealthy aristocrats. Unity and Diana were well known during the 1930s for being close to Adolf Hitler. Jessica turned her back on her inherited privileges and ran away to become a communist. Jessica’s memoir, Hons and Rebels, describes their upbringing, and Nancy obviously drew upon her family members for characters in her novels.

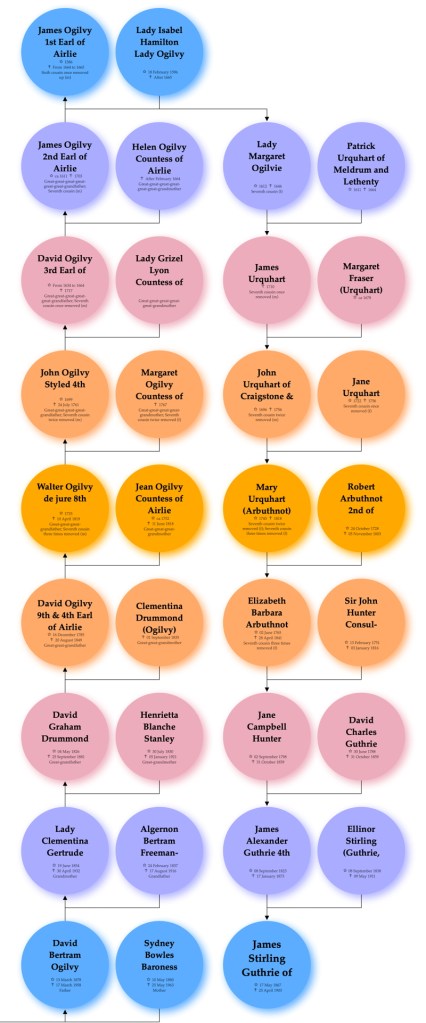

The blood connection between the Guthries and the Mitfords was distant – David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford, 2nd Baron Reedsdale was the seventh cousin of James Stirling Guthrie.

However, by marriage, the ties were much closer – Nancy Mitford, the eldest of the Mitford sibings, married Peter Murray Rennell Rodd, the son of Lilias Georgina Guthrie.

And thus the Guthries were connected to the six Mitford sisters: Nancy, the famous author; the retiring and private Pamela; Diana, a notorious fascist; Unity, the close friend of Adolph Hitler; Jessica the communist and Deborah, the duchess. (There was also a brother, Major Tom, but he died during the Second World War, and people tend to remember only the six sisters.)

So many column inches have been devoted to the Mitford sisters and so many letters and books written both by and about them that we need only touch here on a few more personal and less well known stories.

Deborah Vivien Freeman-Mitford, Duchess and Dowager Duchess of Devonshire (31 March 1920 – 24 September 2014)

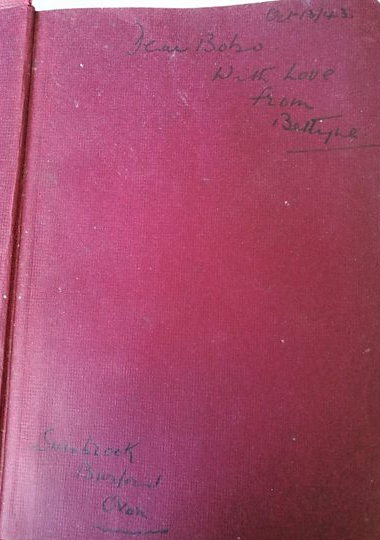

I had a French friend who was an avid reader of books in English and who was fascinated by the story of the Mitfords, so when I was at Chatsworth, I managed to get the then Dowager Duchess of Devonshire to sign copies of her many books, which made ideal gifts. She was very active in running the estate and would sometime even work the tills at the entrance. I also kept several signed copies of her books for myself.

When she passed away on 24 September 2014, we raised a glass or two to her memory.

Unity Valkyrie Freeman-Mitford (8 August 1914 – 28 May 1948)

More recently, a friend mentioned that one of his retired neighbours, Margaret Laidlaw, who had been made an MBE for her fundraising for the children’s charity UNICEF, had come to visit to enquire about his mother. While there, Mrs Laidlaw told him in considerable detail that when she was a young girl, Unity Mitford had lived with her family. I assumed that he was pulling my leg, but it turned that the story was true!

Unity Mitford, the fourth sister, was, like her elder sister Diana an active fascist and great admirer of Adolf Hitler. However, the Mitfords were far from being alone. In the 1920s and 1930s, especially during the time of appeasement, many aristocrats feared a repeat of the Russian Revolution in the United Kingdom and as the enemies of communists, they believed that the fascists were their friends and allies.

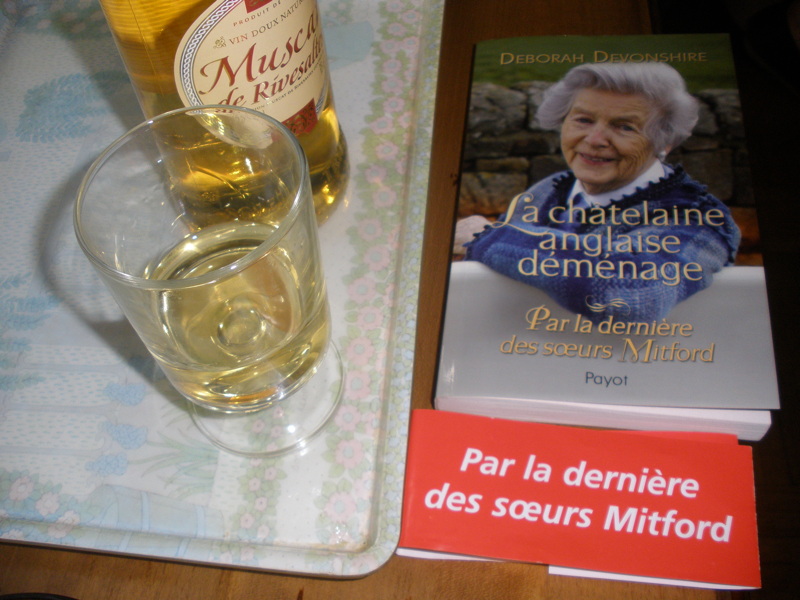

In January 1934, Viscount Rothermere wrote an article for the Daily Mail entitled “Hurrah for the Blackshirts” celebrating Diana Mitford’s husband Sir Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Three years after “Hurrah for the Blackshirts“, in October 1937, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor visited Nazi Germany, against the advice of the British government, and met Adolf Hitler at his Berghof retreat in Bavaria. The visit was much publicised by the German media. During the visit the Duke gave full Nazi salutes. In Germany, “they were treated like royalty … members of the aristocracy would bow and curtsy towards her, and she was treated with all the dignity and status that the duke always wanted“, according to royal biographer Andrew Morton in a 2016 BBC interview.

Diana and Unity Mitford spent a great deal of their time in Germany and after engaging in what would now be known as stalking, Unity met Adolf Hitler and they became close friends. Hitler was fascinated by Unity’s middle name, Valkyrie; he was a great admirer of Richard Wagner whose operas included Die Walküre (The Valkyrie). In 1939, some time before the Second World War started, Diana and her husband Sir Oswald Mosely moved back to Britain, but Unity decided to stay in Germany. When war broke out between Britain and Germany, Unity was so conflicted that she decided to commit suicide in the English Gardens in Munich using a pearl pistol, which was a gift from the Führer himself.

She told me that if there was a war, which of course we all terribly hoped there might not be, that she would kill herself because she couldn’t bear to live and see these two countries tearing each other to pieces, both of which she loved.

Diana Mitford in 1999.

Although Unity Mitford shot herself in the head and the bullet lodged in her brain, she did not die and was taken to hospital in Munich. Hitler himself frequently visited her, paid her medical expenses and arranged for her to be taken to Bern, in neutral Switzerland.

We were not prepared for what we found – the person lying in bed was desperately ill. She had lost two stone, was all huge eyes and matted hair, untouched since the bullet went through her skull. The bullet was still in her head, inoperable the doctor said. She could not walk, talked with difficulty and was a changed personality like one who had had a stroke. Not only was her appearance shocking, she was a stranger, someone we did not know. We brought her back to England in an ambulance coach attached to a train. Every jolt was agony to her.

Deborah Mitford In a 2002 letter to The Guardian.

Stating she could remember nothing of the incident, Mitford returned to England with her mother and sister in January 1940 amid a flurry of press interest.

“I’m glad to be in England, even if I’m not on your side.”

Unity Mitford, January 1940.

Unity Mitford’s support for the Nazis and her outspoken comments led to public calls for her internment as a traitor. Due to the intervention by Home Secretary John Anderson, at the behest of her father, she was permitted to stay with her mother at the family home at Swinbrook, Oxfordshire. Under the care of Professor Hugh Cairns, neurosurgeon at the Nuffield Hospital in Oxford, “She learned to walk again, but never fully recovered. She was incontinent and childish.” Her mental age was likened to that of a 10 year old, or a “sophisticated child” as James Lees-Milne called her (although he added that she was “still very amusing in that Mitford manner“). She had a tendency to talk incessantly, had trouble concentrating her mind, and showed an unusually large appetite with sloppy table manners. Lees-Milne observed her to be “rather plain and fat, and says she weighs 13+1⁄2 stone“. She did however, retain at least some of her devotion to the Nazi party; her family friend Billa Harrod recalled Unity stating that she wished to have children and name the eldest Adolf!

Up until 11 September 1941, Unity Mitford was reported to have had an affair with RAF Pilot Officer John Andrews, a test pilot, who was stationed at the nearby RAF Brize Norton. MI5 learned of this and reported it to Home Secretary Herbert Morrison in October. He had heard that she “drives about the countryside … and picks up airmen, etc, and … interrogates them.” Andrews, a former bank clerk and a married father, was “removed as far away as the limited extent of the British Isles permits.” He was re-posted to the far north of Scotland where he died in a Spitfire crash in 1945. By then, the authorities had concluded that Unity Mitford did not pose a significant threat.

In the spring of 1948, Unity Mitford became seriously ill on a visit to the family-owned island of Inch Kenneth, off the west coast of the Isle of Mull, at the entrance of Loch na Keal, to the south of Ulva. She was taken to the local hospital at Oban. Doctors had decided it was too dangerous to remove the bullet in her head and on 28 May 1948, Unity Mitford died of meningitis caused by the cerebral swelling around the bullet.

Unity Mitford was buried at Swinbrook Churchyard between her sisters Nancy and Diana. The inscription on her gravestone reads: “Say not the struggle naught availeth.“

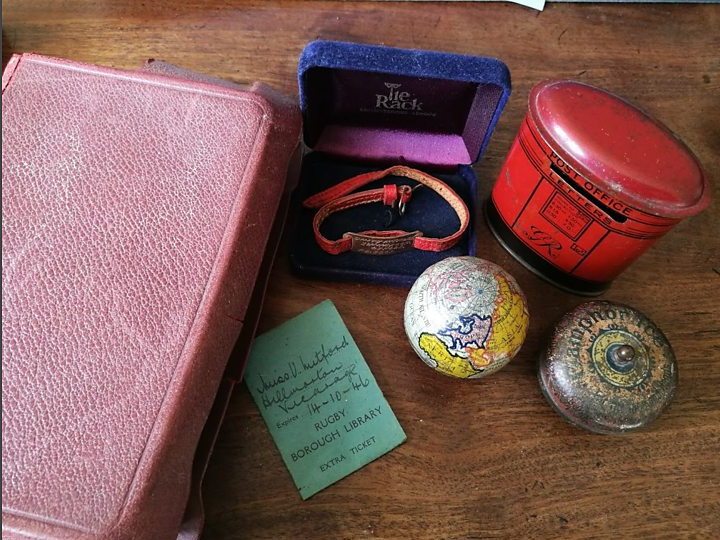

A Nazi at the Vicarage

But that was not the full story, there was another chapter that until recently was not widely known. From 1943, Unity Mitford also spent long periods at the Vicarage in Hillmorton, an area of Rugby in Warwickshire, staying with the wife of the local vicar, and his family- Margaret Laidlaw’s parents and sisters.

“It was decided the vicarage in Hillmorton was a safe enough haven for Unity – a place where she could receive the care she needed and live a less troublesome existence.

“Lady Redesdale, Unity’s mother, was a client of Margaret’s mother, a chiropodist, and it was agreed Mrs Sewell-Corby could act as Unity’s nurse.

“The vicarage was always open to everyone,” Margaret said. “People that were down-and-outs came and asked us for a cup of coffee.

“My mother obviously thought it would be kind to have her. No doubt there was a lot of government correspondence going on.

“I think [my father] found it very, very difficult. He was doing his wartime effort, which was to look after a potentially dangerous person.

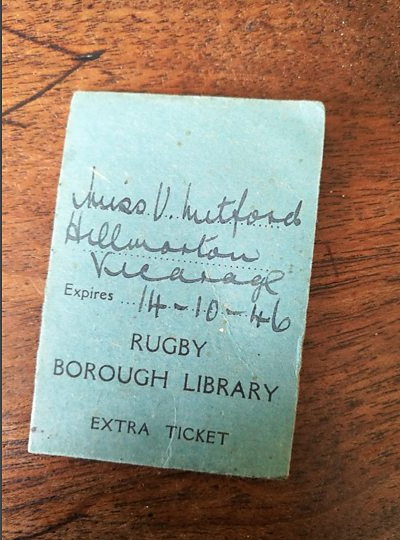

“Unity had no money, she had no passport, she had no writing paper. She was allowed absolutely nothing at all. For a while, she wasn’t even allowed a library ticket.”

The first memory Margaret Laidlaw has of Unity Mitford is of her standing under a chestnut tree in Leamington Spa with Margaret’s mother.

Margaret, who was eight years old, remembers the most notorious of the Mitford sisters looked like nobody she had ever seen before.

“She was very tall with a lovely ruby brooch at her neck – she always wore that. She had fair hair. That’s my first real memory of her,” Margaret said.

“My mother said, ‘This is Auntie Unity and she may be coming to stay with us’. I remember feeling confused – I had never heard any mention of an Auntie Unity.'”

“A few weeks after that first introduction, Unity was installed as a permanent house guest at the vicarage in Hillmorton, Warwickshire, where Margaret lived with her father the Rev Frederick Sewell-Corby, her mother Bettyne and her younger sister.

“Margaret remembers watching bewildered as her father’s clothes and books were removed from her parents’ bedroom.

“Margaret’s mother had to sleep in the same room as Unity and nurse her through the night.

“Unity was incontinent – I knew this from the sheets galore that were hung out on the line each morning,” Margaret said. “And she had a leg that was paralysed and swung like a log when she walked.”

“Margaret’s father went to sleep in his dressing room and locks and bars went on all the vicarage doors and windows.

“I think Unity was under what you and I would call house arrest,” Margaret said. “She was never, ever alone.”

“But unbeknown to the little girl, “Auntie Unity” was no relative and her reputation was notorious.

“She had been discussed in the House of Commons. Her whereabouts was considered to be a matter of national security.

“For she was rumoured to be the girlfriend of Adolf Hitler himself.

“She was always very cheerful, very jolly,” Margaret Laidlaw said. “She was a very good artist. We used to pick ragged robin and dog roses on the country lanes and we would come back and she would show us how to paint them.

“I don’t remember being in the room with her for any length of time on our own. Mother was always there, knitting or playing the piano.

“My memory is that Unity liked Bavarian marching songs and would stride around singing. I remember she had a record player and a lot of 78 records. She was a very good singer – a bit loud and very spontaneous.”

Margaret now believes she and her sister were protected by their mother and father from some of Unity’s more extreme views.

“I’m sure our parents were very careful,” she said. “There was great emphasis on the fact that the Jews were as good as anybody else.

“In later life, I was horrified to discover Unity was anti-Semitic. I think my parents did a very good job in keeping that one away from us.”

Margaret clearly remembers the final days of the war in Europe, as word of Hitler’s suicide in a bunker in Berlin reached the breakfast tables of Britain.

“My sister said, ‘Morning Auntie Unity. I’m so sorry your boyfriend’s died’ and she said, ‘Oh, you are such a sweet child’,” Margaret recalls.

“And I said, ‘Oh – that man’. And she went for me – she went to kick me and I fled under the dining room table to get out of her reach.”

Later that year Margaret was sent to boarding school. She believes Unity continued to live with the family during term-times but in the holidays travelled to the Scottish island of Inch Kenneth, where she lived with Lady Redesdale.

“Latterly Mother went up there to nurse her because Lady Redesdale knew she could trust my mother implicitly not to say anything to anybody,” Margaret said.

Unity died in 1948 in Oban at the age of 33 as a result of meningitis caused by swelling around the bullet lodged in her brain.

“We came home from school and Mother was upstairs in the bathroom crying,” Margaret remembered.

“I looked at Daddy and he said, ‘Thank God it’s all over.'”

Unity Mitford documentary. 48 minutes, 34 seconds.

Germans stand around Sam’s piano as they sing “Wacht am Rhein”, a German patriotic song about conflicts with France. Laszlo takes command of Rick’s band and has them play “La Marseillaise”, the French National Anthem. The counterpoint of the two is a stunning contrast and bit by bit the crowd gathered in the bar joins in drowning out the Germans. One of the most moving scenes in all of film and especially if you realise that a number of the cast you are watching had actually fled Europe from Nazi occupation and were refugees in America at the time this was filmed.