Humiliation of sitting on the stool, being punished and publicly repenting sins drove some victims to suicide. In the case of pregnant women of such parishes who had not conceived with their husbands, they would often elaborately conceal their pregnancy or attempt infanticide rather than face the congregation then Kirk Session.

Stool of repentance

Scottish Indexes Conference XI

The latest Scottish Indexes conference on Saturday 10th July 2021 revealed a potential family mystery that has yet to be solved!

On Saturday, Scottish Indexes held their eleventh in their series of excellent and informative online conferences, which this time included a talk by Kirsty Wilkinson entitled:

TRACING SCOTTISH WOMEN

“We’re delighted to announce that Kirsty Wilkinson will be joining us at our conference in July to present ‘Tracing Scottish Women’. Traditionally, genealogies followed the male surname line with little attention paid to female ancestors. Although that is less the case with family history today, the fact that women typically generated fewer records than men means they can often be more difficult to research. This presentation will look at some of the challenges of tracing women in Scotland, as well as highlighting some of the records that can shed light on their lives and bring their individual stories to life. Kirsty F. Wilkinson has worked as a professional genealogist since 2006 and holds an MSc in Genealogical, Palaeographical and Heraldic Studies from the University of Strathclyde. After successfully running her own family history research business for over ten years, Kirsty joined AncestryProGenealogists, the research division of Ancestry.com, in 2017 where she continues to specialise in Scottish research. Kirsty’s first book, ‘Finding Your Scottish Ancestors: Techniques for Solving Genealogy Problems’ was published by Robert Hale in 2020.”

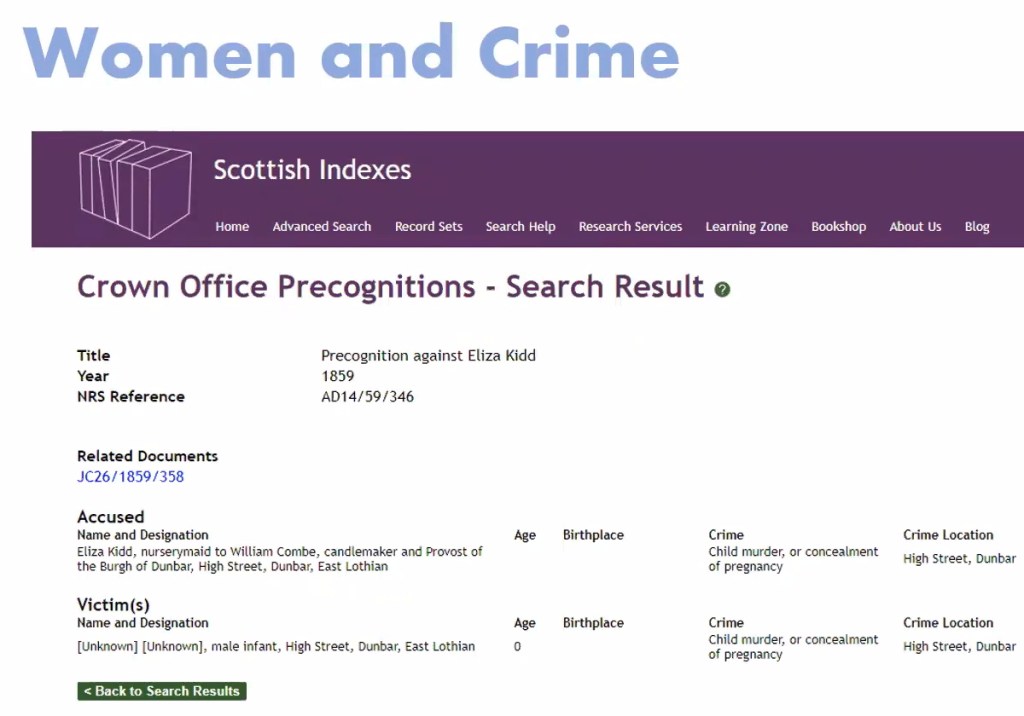

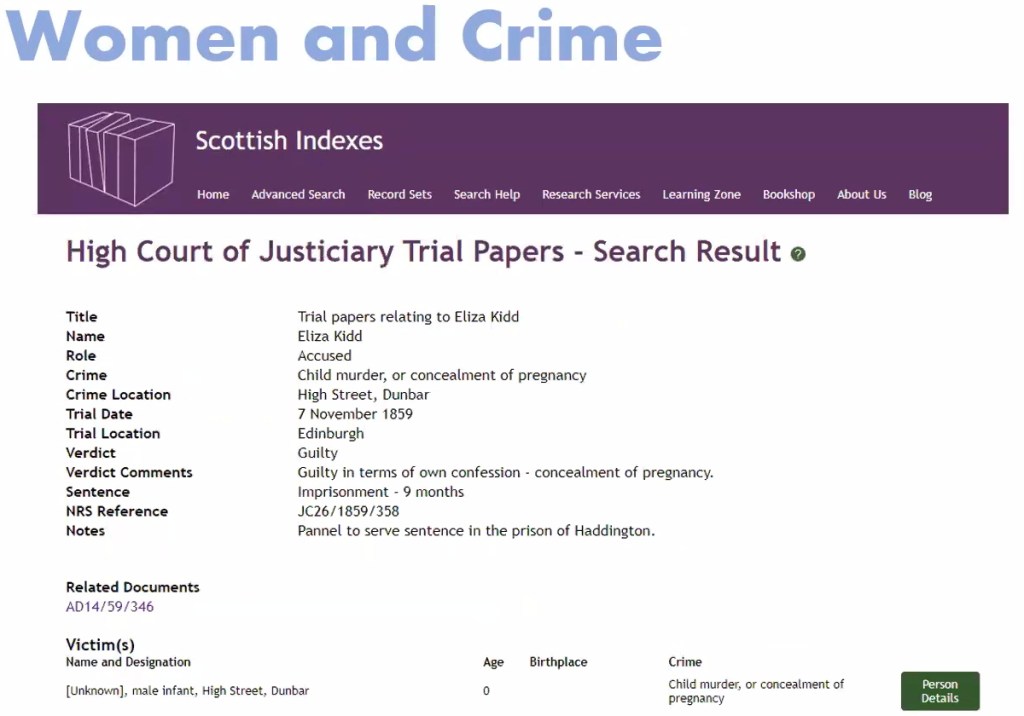

During the talk, I almost fell off my seat when Kirsty Wilkinson presented two slides detailing the trial of an Eliza Kidd from right here in the High Street in Dunbar, East Lothian, for “Child murder, or concealment of pregnancy“.

My great grandmother, Elizabeth Selkirk Kidd, was born in Haddington in 1850, so this was clearly not her, as she would have been nine at the time. But could Eliza be one of her relatives as there were other Elizabeths in the family?

I asked Kirsty Wilkinson whether she had any further details, but the National Records of Scotland had been closed and it turned out she had chosen the case simply as an example.

Order a Copy of the Precognition, Trial Papers and Trial Minutes

These records can help you trace your family tree and understand the lives of your ancestors. Order a copy of the Precognition, Trial Papers and Trial Minutes for £45.00. Watch our video to find out what you will receive. The records of the High Court are truly amazing and are one of the most comprehensive sources relating to your family you are likely to find. The witness statements are fascinating and give us a glimpse into our past. To find out more about these wonderful documents visit our Learning Zone.

There are three main sets of records relating to each trial and we can help you access these by providing high quality images for a small research fee. You can either order all three (recommended) or you can order the trial papers alone (see below). If you have any questions please contact us and we can advise you.

The precognition was made before the trial and may contain information not used at trial. The indictment is usually contained in the precognition papers and this will give you an outline of the facts of the case, but the main part of the precognition is normally made up of detailed witness statements.

The trial papers or ‘High Court of Justiciary Trial Papers’ contain some of the same information that you will find in the precognition, but you will also find additional information. Any paper evidence supplied to the court such as maps etc. will be contained in these records. You can see an example of one of the exciting items we found in our Learning Zone.

The minute book is the third record we recommend searching. Although briefer than the precognition and trial papers, this record tells you what happened on the day(s) of the trial and the outcome of the case, it completes the picture.

For the research fee of £45 we will copy all three of these records for you (please note that if the case is particularly extensive we will limit the research time to 80 minutes). By clicking ‘Add to Cart’, you will place an order for this entry in your PayPal ‘Shopping Cart’. There is a link to the Shopping Cart at the foot of each page on the site so that you can review or amend your order at any time.

Normally, these records can be ordered through Scottish Indexes, but as National Records of Scotland are only just starting to open up again Kirsty Wilkinson and Graham and Emma Maxwell of Scottish Indexes suggested searching online newspaper archives for further information.

Newspaper Reports of the Trial

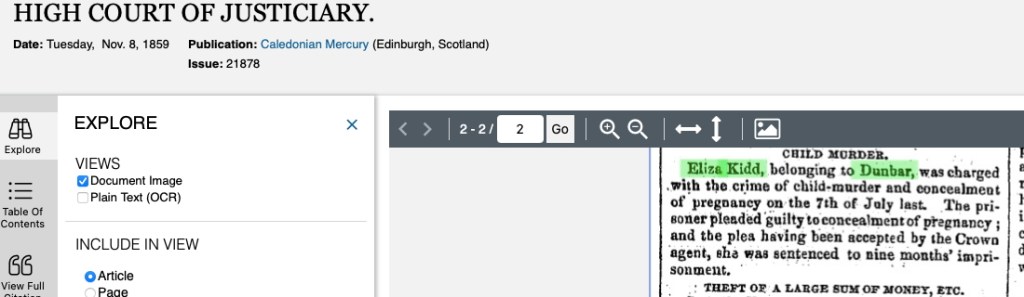

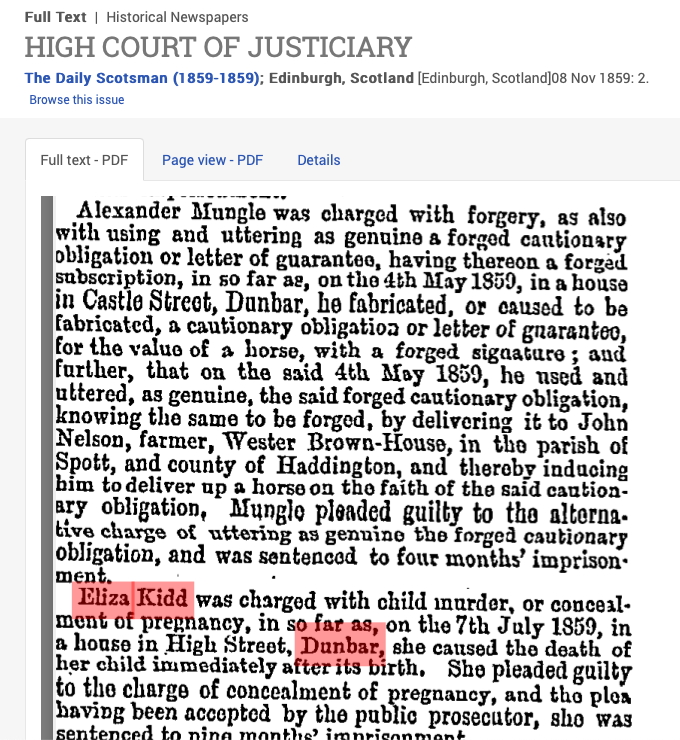

I found a couple of brief reports in the Caledonian Mercury and in the Scotsman dated 8th November 1859.

These reports did not add a great deal to the information given in the indexes, but revealed that the crime had been committed on 7th July 1859.

The best bet seemed to be the local newspaper, the East Lothian Courier.

According to the John Gray Centre‘s index, a report on the trial appeared in the index for the East Lothian (then Haddingtonshire) Courier of 11th November 1859 under “Kidd, Eliza: Murder Charge: Dunbar, Page 3, Column 1“.

Unfortunately, I was unable to locate this issue in the British Newspaper Archive.

The John Gray centre archive does include back issues of the Courier, so a visit to Haddington seems to be called for.

The Employer: William Combe, Provost of Dunbar

Eliza Kidd was described as “nurserymaid to William Combe, candlemaker and Provost of the Burgh of Dunbar, High Street, Dunbar, East Lothian.“

The John Gray Centre in Haddington has a biography of William Combe included in their excellent Provosts of Dunbar series:

“William Combe (1810 – 1898) was the son of Dunbar’s tobacconist & chandler George Combe and Agnes Hewit his spouse. William followed his father into chandlery (the supply of equipment for ships and boats) but concentrated on the family’s other venture – candlemaking. His works were just behind the High Street on the west side (a building later used by Aitken’s lemonade factory).William became provost in the mid 1850s having served some years as bailie (magistrate). The early part of his provostship was dominated by attempts to secure funding for improvements to Victoria Harbour and the militia question. In early 1855 Dunbar had been chosen as HQ for the newly raised artillery militia of several counties. Dunbar protested because ‘billeting in a town like Dunbar would be a severe tax on the inhabitants’. The case for a barracks was made and won: in December 1855 Dunbar Barracks was ’at present being prepared’. The militia only required full use of their site in the summer months, consequently William was able to report in 1857 that, having written to Government, he was pleased to report that Lord Panmure wrote back ‘making over the park to the Magistrates and Corporation for the use of the inhabitants’ as a ‘recreation ground’ – Dunbar’s first public park (except in the summer months when the militias were embodied).The end of William’s spell as provost coincided with the rise of the ‘Young Coach’ party on the council. For some years prior to 1861, elections ‘had been very severe, but this year more so than others’. Each faction put forward five candidates and the ‘Young Coach’ swept the board, trouncing two sitting candidates of the ‘Old Coach’ and their three aspirants. Charles Lorimer Sawers became provost instead of William.“

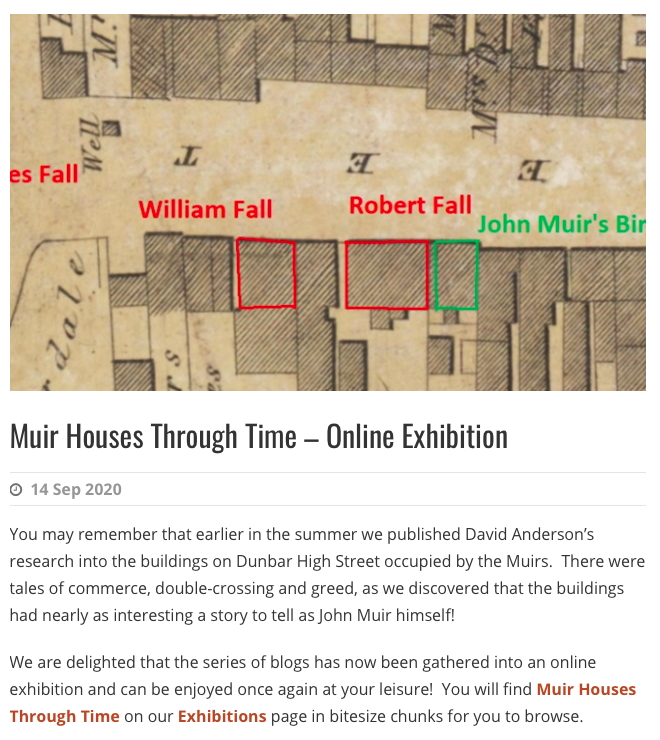

The Location: 140 High Street?

According to the reports, the crime was committed in the High Street and Eliza Kidd was described as nurserymaid to William Combe, candlemaker and Provost of the Burgh of Dunbar.

In 1861, William Combe’s address is simply given as “High Street”. However, in 1881 he was living at 140 High Street.

His works were described by the John Gray centre as “just behind the High Street on the west side (a building later used by Aitken’s lemonade factory)” which would tie in with this address.

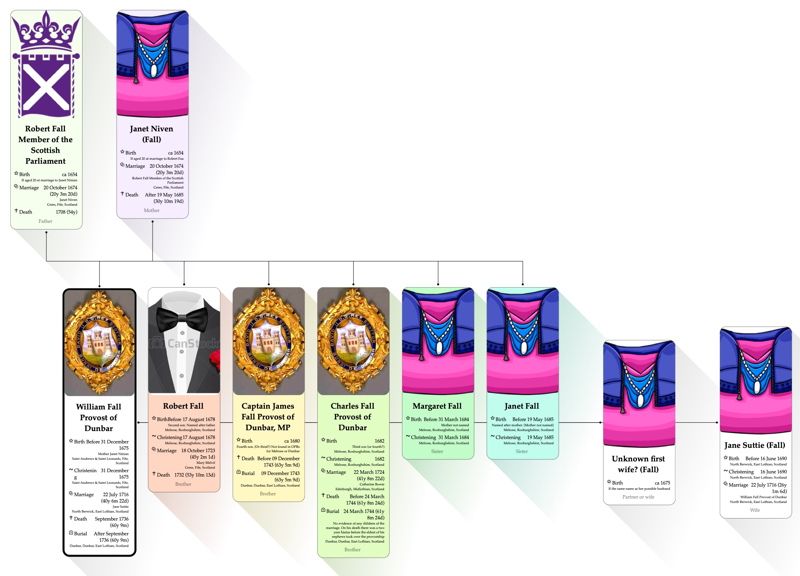

The Rise and Fall of the House of Fall, Uncrowned Kings of Dunbar

The Fall dynasty were powerful merchants who provided the Provosts of Dunbar continually from 1730 until 1789 with the exception of two years when no member of the family was old enough to hold the office.

Local historian, David Anderson has done a considerable amount of research into the houses occupied by the family of John Muir and of the Falls, early Provosts of Dunbar. This has been published by John Muir’s Birthplace.

140 High Street, where William Combe was living in 1881 – and perhaps also in 1869 – was once owned by William Fall, one of the all-powerful family who were practically hereditary Provosts of Dunbar.

According to the John Gray Centre:

“All good things come to an end. Deaths left Robert as the sole representative of the family still in business and when banking prudence overcame family ties he was forced to liquidate many of his ventures. In 1788 the earl of Lauderdale bought many of the Dunbar assets – but not all; Robert retired and died in 1796. However, before then activity went on under his wife’s name and land reclamation schemes, a spinning school and a textile factory at Belhaven continued until her death in the early part of the nineteenth century.“

1830: Owned by Mrs Miller

By the time of John Wood’s 1830 town plan of Dunbar, William Fall’s house was owned by a Mrs Miller.

1855: Possibly owned by William Comb

The Valuation Rolls for 1855 reveal that William Comb Esquire was the proprietor and occupier of a house, shop, garden and Candle Work at High Street Dunbar.

While not proven, as the address is not given in the index, it is assumed that these are the premises at 140 High Street where the crime of 1869 took place.

| COMB | WILLIAM | ESQUIRE | Proprietor Occupier | HOUSE SHOP GARDEN AND CANDLE WORK HIGH STREET DUNBAR | DUNBAR | 1855 | VR002500001 |

The Accused: Eliza Kidd

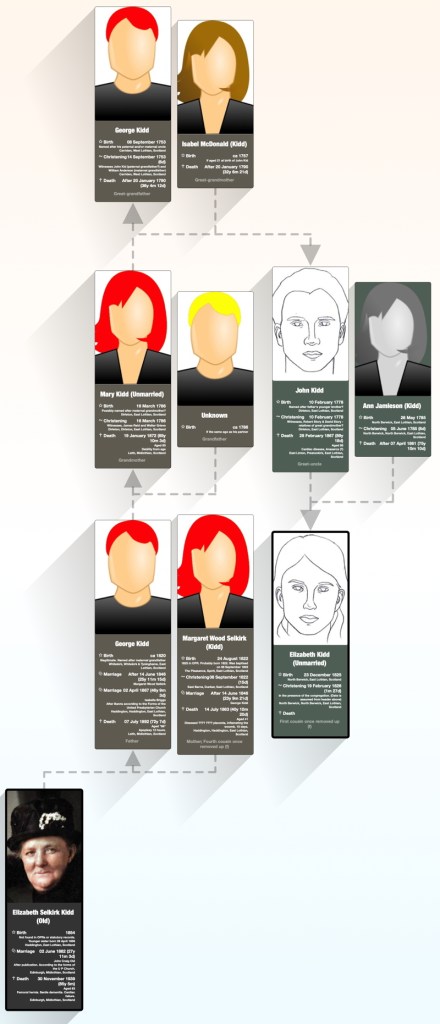

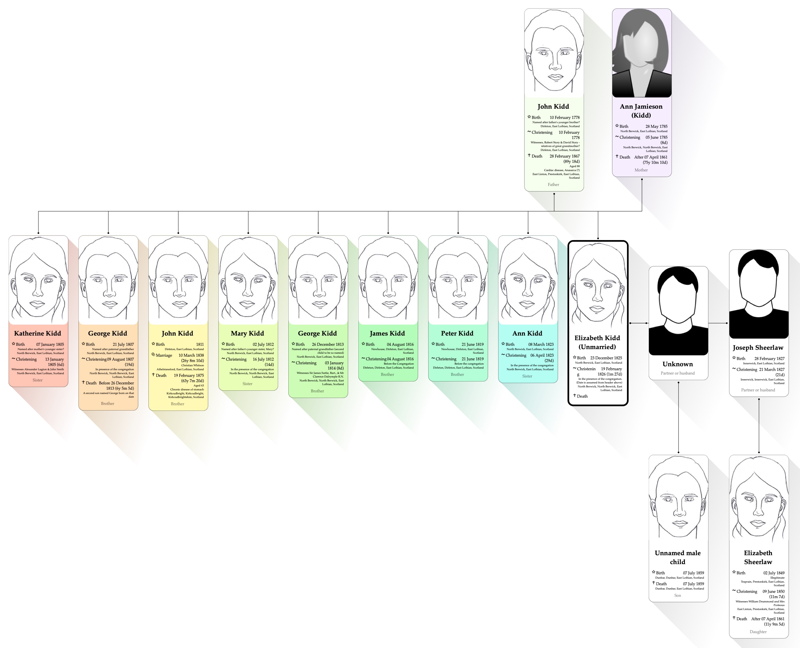

Who exactly was Eliza Kidd? Without being able to see the trial documents, it is difficult to be sure, but one possibility might be the Elisabeth Kid who was born in North Berwick parish on 23 December 1825, the first cousin once removed of our great grandmother Elizabeth Selkirk Kidd.

There were a considerable number of illegitimate births in the Kidd family over several generations: Our great grandmother’s paternal grandfather is still a mystery man – although this is being investigated using DNA – while she herself had two illegitimate children before she married our great grandfather and went on to have ten children with him!

23 December 1825: Birth, Parents and Siblings

Elisabeth Kid was born in North Berwick parish in East Lothian on 23 December 1825 and baptised on 19 February 1826 in presence of the congregation.

She was the ninth and last known child of John Kidd (aka Kid and Kyd), an agricultural labourer and his wife Anne Jamieson.

She had eight elder siblings:

- Katherine Kid, born 07 January 1805 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on 13 January 1805 with witnesses Alexander Lugton & John Smith.

- George Kyd, born 21 July 1807 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on 09 August 1807 in presence of the congregation. He is assumed to have died before 26 December 1813 as a second son named George was born on that date.

- John Kidd. Born circa 1811 in North Berwick parish. No trace of his birth or baptism has been found in the OPRs. He married Christina Whitson on 10 March 1838 in Athelstanesford, had nine children and died on 19 February 1875 aged 63 at Town end in the town of Kirkcudbright in Kirkcudbrightshire.

- Mary Kidd, born 02 July 1812 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on 16 July 1812 in presence of the congregation. It is not known whether she survived infancy and went on to marry and have children.

- George Kid, born 26 December 1813 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on 03 January 1814. The witnesses to the baptism were two of the local gentry, “Sir James Suttie, Bart., & Mr Clarence Dalrymple R.N.” (Sir James was the grand nephew of Jane Suttie, second wife of William Fall, Provost of Dunbar, mentioned above.) This baptism is perhaps worthy of an article of its own. It is not known whether he survived infancy and went on to marry and have children.

- James Kid, born on 04 August 1816 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on an unspecified later date in presence of the congregation. It is not known whether he survived infancy and went on to marry and have children.

- Peter Kidd was born on 21 June 1819 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on an unspecified later date in presence of the congregation. It is not known whether he survived infancy and went on to marry and have children.

- Ann Kid was born on 08 March 1823 in North Berwick parish in East Lothian and baptised on 06 April 1823 in presence of the congregation. It is not known whether she survived infancy and went on to marry and have children.

02 July 1849: Birth of an illegitimate daughter, Elizabeth Shearlaw

After her birth, Elisabeth Kid’s next appearance in the records was on 02 July 1849 when, as Elizabeth Kid, she gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, Elizabeth Sheerlaw at Traprain in Prestonkirk parish.

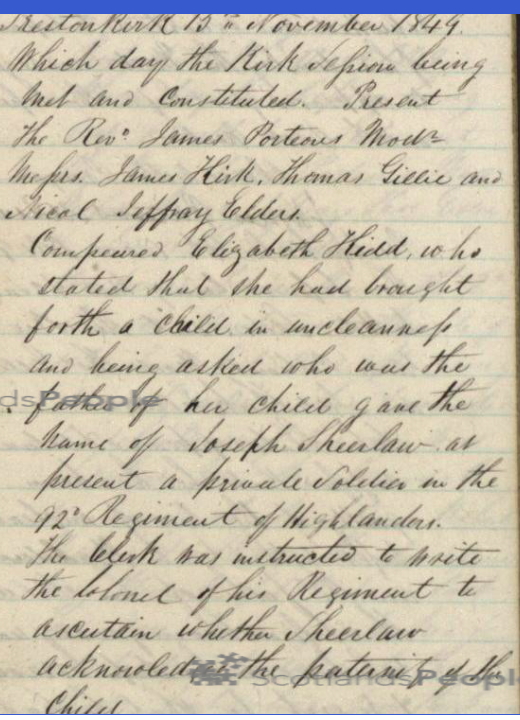

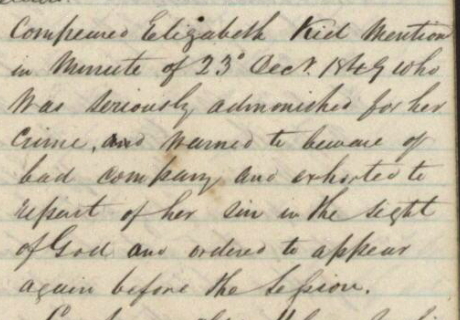

15 November 1849: Compeared Before the Prestonkirk Kirk Session

The original church is said to have been founded by Saint Baldred of Tyninghame, also known as Saint Baldred of the Bass, in the 6th century. The tower of the present church dates from 1631, and the main building from 1770. It was enlarged in 1824 and the interior was redesigned in 1892. The Saint Baldred window was installed in 1959.

The recent publication of the Kirk Session records on ScotlandsPeople has allowed further research to be carried out.

As might be expected, Elizabeth Kidd had been ordered to appear before the Kirk Session at Prestonkirk in East Linton before the Reverend James Porteous, Moderator of the Kirk Session along with Messrs. James Kirk, Thomas Gillie, and Nicol Jeffray, Elders.

According to the official record, Elizabeth Kidd “stated that she had brought forth a child in uncleanness!”

When asked the name of the father of the child, she “gave the name of Joseph Sheerlaw, at present a private soldier in the 92nd Regiment of Highlanders.“

“The Clerk was instructed to write the Colonel of his Regiment to ascertain whether Sheerlaw acknowledged the paternity of the child.“

Note: the 92nd Regiment of Highlanders is better known as the Gordon Highlanders.

From 1842 until 1855, the Colonel of the Regiment was Lt-Gen. Sir William Macbean, KCB.

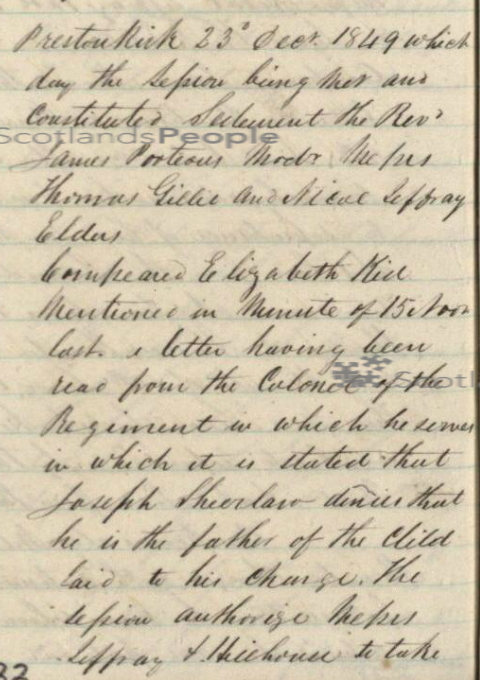

23 December 1849: James Sheerlaw Denies Paternity

Elizabeth Kid was recalled before the Kirk Session on 23rd December 1849 before the Reverend James Porteous, Moderator of the Kirk Session along with Messrs. Thomas Gillie, and Nicol Jeffray, Elders.

A letter from the Colonel of Regiment in which James Sheerlaw served (92nd Regiment of Highlanders) was read in which “it is stated that Jospeh Sheerlaw denied that he is the father of the child laid to his charge.”

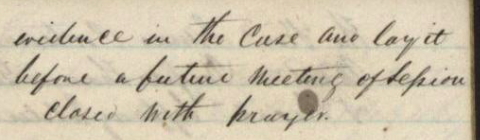

“The Session authorised Messrs Jeffray and Hillhouse to take evidence in the case and lay it before a future meeting of Session.”

31 March 1850 Admonished by the Kirk Session

Elizabeth Kid appeared for the third time before the Kirk Session of Prestonkirk in East Linton at a meeting of 31 March 1850 which was Moderated by the Reverend James Porteous with Messrs. Nicol Jaffrey and Thomas Gillie, Elders also attending.

Elizabeth Kid “was seriously admonished for her crime and warned to beware of bad company and exhorted to repent of her sin in the sight of God and ordered to appear again before the Session.“

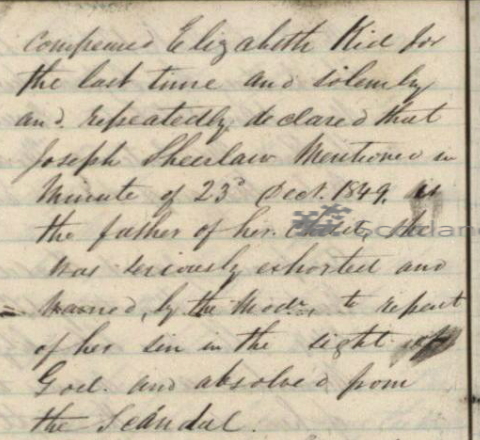

19 May 1850: Repeatedly Declared That Joseph Sheerlaw Was the Father Of Her Child

On 19th May 1850, Elizabeth Kid was summoned before the Kirk Session of Prestonkirk at East Linton for the fourth and final time. The meeting was Moderated by the Rev. Mr Porteeous with Messrs Thomas Gillie, James Kirk and Nicol Jeffray, Elders.

Elizabeth Kid “solemnly and repeatedly declared that Joseph Sheerlaw … was the father of her child.”

“She was seriously exhorted and warned by the Moderator to repent of her sin in the sight of God and absolved from the Scandal.“

09 June 1850 Baptism of daughter Elizabeth Sheerlaw

We believe that Joseph Sheerlaw, the father of Elizabeth Sheerlaw, was born on 28 February 1827 at Innerwick parish in East Lothian to Joseph Sheerlaw senior, an agricultural labourer and his wife Rebecca Douglas.

Before the Kirk Session records were consulted, it had been believed that although he did not marry Elisabeth Kid, James Sheerlaw had acknowledged his paternity.

However, from Elizabeth Kid’s various appearances before the Prestonkirk Kirk Session. it is clear that James Sheerlaw, then a private soldier in the Gordon Highlanders, had denied that he was the father of the child.

Despite James Sheerlaw’s denials, on 09 June 1850, Elizabeth Kidd’s daughter was finally baptised, almost a year after her birth, as Elizabeth Sheerlaw, with witnesses William Drummond and Mrs Porteous.

30 March 1851 Living at Traprain with her parents

At the census of 30 March 1851, Elisabeth Kid was recorded at Traprain in the parish of Prestonkirk as Elizabeth Kidd, aged 24, an agricultural labourer, born North Berwick parish.

She was living with her parents, John and Ann Kidd, then aged 72 and 66 respectively.

Also in the household was Ann’s mother, Elizabeth Dobie, who seemingly had reached the grand old age of 96!

There was also a Fanney Kidd, aged 13 and an agricultural labourer. She was listed as John Kidd’s “daughter” but was more likely to be an illegitimate granddaughter. It is possible that she was one of two daughter of Elizabeth’s eldest sister, Katherine.

After 1851?

At the census of 07 April 1861, Elisabeth Kid’s daughter Elisabeth Sheerlaw was aged 11 and living with her maternal grandparents John and Ann Kidd, then aged 82 and 75 respectively at Eastside on Linton Road in Prestonkirk parish.

However, of Elisabeth herself, we could find no trace and we wondered whether she might have married, emigrated or died before Statutory Registration of deaths had commenced in January 1855?

Crime and Punishment

Stool of repentance and branks, Holy Trinity Church, St. Andrews. Photo credit: Kim Traynor.

It is not known whether Elisabeth Kid’s admonishment in 1850 had included the Stool of Repentance.

Wikipedia notes that women subjected to such humiliation sometimes committed suicide, concealed their pregnancy or attempted infanticide.

“The stool of repentance in Presbyterian polity, mostly in Scotland, was an elevated seat in a church used for the public penance of persons who had offended against the morality of the time, often through fornication and adultery. At the end of the service the offender usually had to stand upon the stool to receive the rebuke of the minister. It was in use until the early 19th century.

Humiliation of sitting on the stool, being punished and publicly repenting sins drove some victims to suicide.[1] In the case of pregnant women of such parishes who had not conceived with their husbands, they would often elaborately conceal their pregnancy or attempt infanticide rather than face the congregation then Kirk Session.[1]

An alternative to, or commutation of, the stool of repentance was payment of buttock mail.[2]

A harp tune commemorates the tradition.“

It is difficult, and not always advisable, for those of us living in the modern era to pass judgement on the morals and behaviour of those who lived in different times.

However, if Elisabeth Kid and Eliza Kidd were the same person, then it is sad to think that the fear of a repeat of her previous public humiliation in 1850 for having an illegitimate child may have prompted Eliza Kidd to murder her newly born son nine years later.

The Verdict

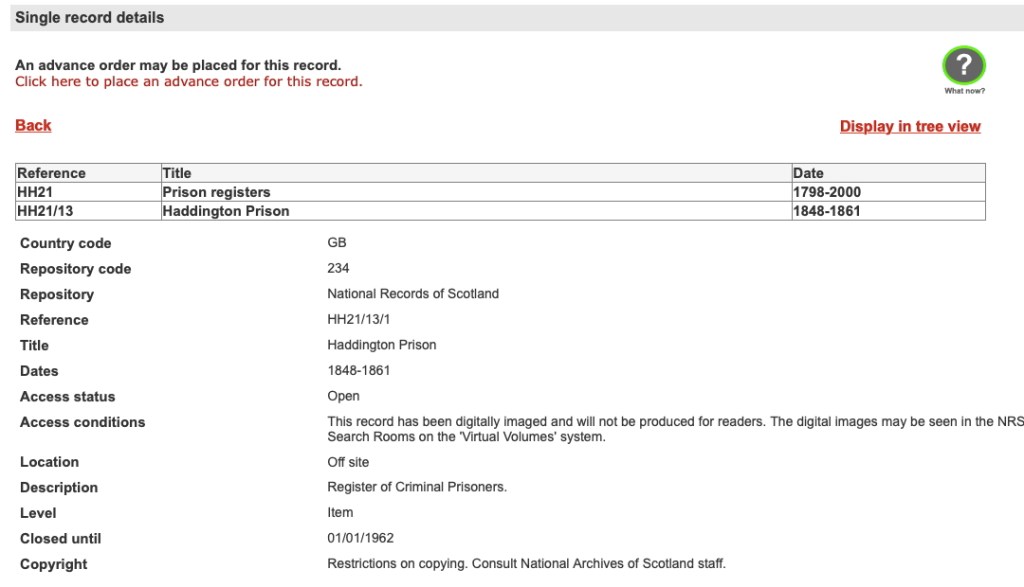

Could our Elisabeth Kid be the Eliza Kidd who was sentenced to nine months in Haddington Prison in 1859?

Would an agricultural labourer have been hired by the Provost of Dunbar to act as nurserymaid to his children?

Quite possibly, as Elisabeth’s father, John Kid, had worked as a servant at Newhouse and he obviously knew members of the local gentry well enough for them to act as sponsors at the baptism of one of his children.

However at this early stage in the investigation, we can not yet make a positive connection between our Elisabeth Kid and the Eliza Kidd in the court case.

This will require further research, which should prove to be interesting!

According to the John Gray Centre: “The prison registers have been digitised by the NRS and are available on Virtual Volumes in the Historical Search Room and via Scotland’s People.” (I have yet to find them).

Watch this space!

PS In early 2022 the records for Perth Prison became available to search on ScotlandsPeople.

If I remember correctly, Sir James Suttie was the grandson of Lord Prestongrange, of Kidnapped fame, who was the owner of Prestongrange colliery where the Prides and Selkirks worked?

Small world!

So why did two of the local toffs act as sponsors for the child of a labourer?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, in 1818, Sir James Suttie changed his surname to Grant-Suttie upon the death of his aunt, Janet Grant, Countess of Hyndburn when he succeeded inter alia to Prestongrange.

Article in preparation regarding the tangled web spun by the Kidds.

LikeLiked by 1 person