16 June 1338: On this day, 683 years ago, the English under William Montague, Earl of Salisbury gave up their five month siege of Dunbar Castle, whose defence was commanded by Agnes Randolph, Countess of Dunbar.

“Of Scotland’s King I haud my house,

I pay him meat and fee,

And I will keep my gude auld house,

while my house will keep me.“

“She kept a stir in tower and trench,

That brawling, boisterous Scottish wench,

Came I early, came I late,

I found Agnes at the gate.“

Grand Siege of the Castle

The story of Black Agnes was told in James Miller’s 1830 book: The History of Dunbar: From the Earliest Records to the Present Period: with a Description of the Ancient Castles and Picturesque Scenery on the Borders of East Lothian. By James Miller 1830

Chapter VI: Grand Siege of the Castle

At this period the castle of Dunbar was a great annoyance to the English subjects in the Scottish territory. The excursions of the garrison along the fruitful coast, rendered the public road betwixt Berwick and Edinburgh unsafe to travellers, while its port of Lamer Haven, under the shelter of the fortress “grim rising o’er the rugged rock” afforded a safe reception for aids and supplies from France, and other places on the continent. Hence the reduction of this place became of great moment to Edward, on the certain prospect of an immediate war with France.

In January 1377, William Montague, earl of Salisbury, together with the earl or Arundel, to whom the King had left the chief command of the forces in Scotland, attempted this enterprise with a large army. At this important crisis, the earl of Dunbar was engaged with the Guardian in reducing the fortresses in the north; so that the defence of this fortress devolved upon his countess, a lady who, from the darkness of her complexion, was commonly called Black Agnes, but whose vigilant and patriotic conduct has immortalised her name.

Agnes, countess of Dunbar, was daughter to the celebrated Thomas Randolph, earl of Moray, and sister to the earl of that name who fell at Dupplin; and to his successor who was made prisoner in the affray with Count Namur, and who was at this time a prisoner in England. These circumstances inspired sentiments of resentment against the English in the breast of our heroine, which neither the stratagems of art could surprise, nor the terrors of danger dismay. The castle, which was newly fortified, from its situation on rocks nearly surrounded by the sea, was deemed impregnable. But against the natural strength of the fortress we must bring the most consummate generals of the age. Arundel was afterwards constable at the battle of Crecy, and Salisbury commanded the rear at the battle of Poitiers, while the besiegers were the chosen troops that had been victorious in the late invasions.

“‘And do they come?’ Black Agnes cried

‘Nor storm, nor midnight stops our foes;

Well then, the battle’s change be tried,

The Thistle shall out thorn the Rose.’

“She spake and started from her bed,

And cased her lovely limbs in mail;

The helmet on her coal-black head,

Sluiced o’er her eyes, – an iron veil.

“In her fair hand she grasp’d a spear,

A baldrick o’er her shoulder flung;

While loud the bugle note of war,

And Dunbar’s caverned echoes rung. – BLACK AGNES.1

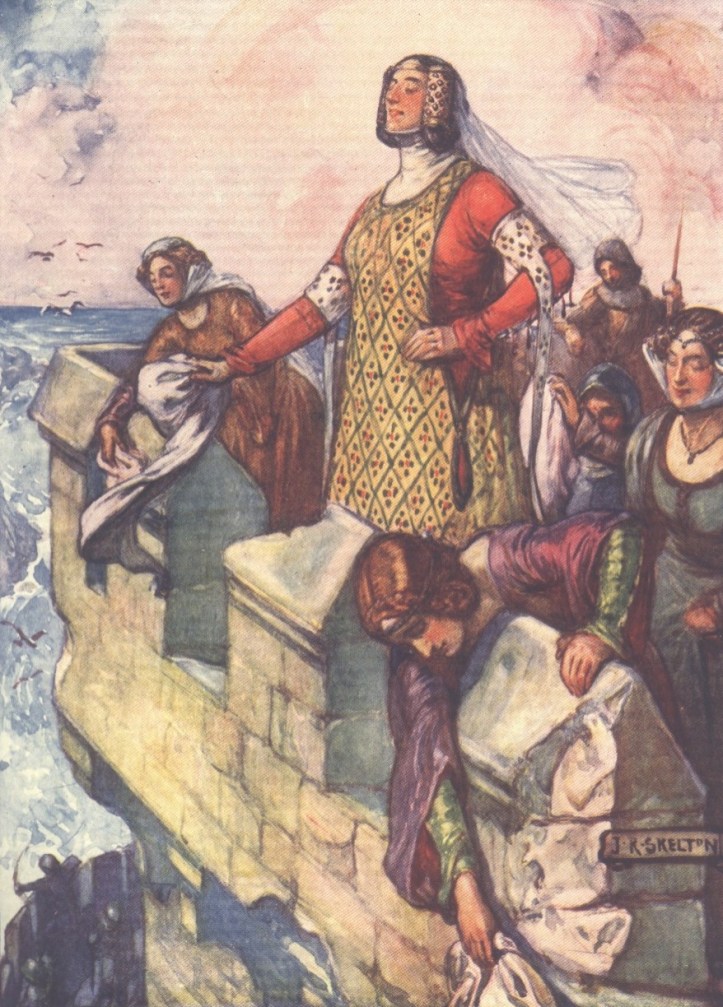

During the siege, Agnes performed all the duties of a bold and vigilant commander. When the battering engines of the English hurled stones or leaden balls against the battlements, she, as in scorn, ordered one of her maids, splendidly drest, to wipe off, with a clean white handkerchief, the marks of the stroke. The castle continued to “laugh a siege to scorn,” when the earl of Salisbury, with great labour, brought that enormous engine the sow2, to bear against the walls; but like the Roman darts at the siege of Jotapata, it rung harmless against the rock.

The countess, who awaited the arrival of this new engine of destruction, being full of taunts, proclaimed:

“Beware Montagow

For farrow shall thy sow.”3

(meaning the men within it) when a large fragment of the rock was hurled from the battlements and crushed the cover to pieces, with the poor little pigs (as Major calls them), who were lurking under it. And although their (sic) is no royal road to poetry, upon the authority of this couplet, Ritsen has admitted Agnes into the company of the Scottish Poets.

Few of the assailants were able to return to their trenches. Finding the arts of forcible and open assault unavailing, Salisbury next attempted to gain access to the castle by treachery. Means were employed to bribe the porter who had charge of the gate. This he agreed to do, but disclosed the transaction to the Countess. Salisbury, at the head of a chosen party, commanded this enterprise in person, and found the gates open to receive him. The officiousness of John Copeland, one of his attendants, saved the general from the snare. Copeland hastily passed before the Earl, the portcullis was let down, and the trusty squire, mistaken for his lord, remained a prisoner. Agnes, who from the souther tower observed the event, cried to Montague jeeringly “Adieu, Monsieur Montague; I intended that you should have supped with us, and assisted in defending this castle against the robbers from England.”

Thus unsuccessful in their efforts, the assailants turned the siege into a blockade and closely environed the castle by sea and land. Amongst the ships were two large Genoese gallies, commanded by John Doria and Nicolas Fiesca. But famine was threatening to effect what force and art could not achieve. In consequence of the protracted siege, the garrison was reduced to the utmost extremities for want of provisions; this intelligence reached Sir Alexander Ramsay, a bold and enterprising officer, who having procured a light vessel with a supply of provisions and military stores, sailed in a dark night, with forty chosen companions from the Bass, and, eluding the vigilance of the enemy, he entered the castle by a postern next to the sea, and brought relief and refreshment to the desponding soldiers. Next morning, Ramsay made a smart sortie on the besiegers, killing and surprising them at their posts, and taking many prisoners; and the same night he completed the glory of his stratagem by passing from the castle in the same manner, and with the same safety, with which he had entered.

The English having vigorously prosecuted the siege for six weeks, were compelled to abandon this hopeless enterprise.3 Besides the commanders of the army, there were present on this occasion, the Earl of Gloucester, Lords Percy and Neville. Holinshed asserts that Edward was present himself. At all accounts, he spent some days at Berwick at that period, and if he was not present, at least gave orders to abandon the siege of Dunbar.

While the Countess thus gallantly defended her husband’s “strong house4 at Dunbar, he was employed along with the Guardian, Sir William Douglas, and other loyal nobles, in reducing the fortresses on the other side of the Forth. After defeating a great body of Englishmen at Panmure, they took the castles of St Andrews and Leuchars, and the tower of Falkland, and destroyed them: the castle of Cupar alone resisted their utmost efforts. In March they reduced the castle of Bothwell, while this extraordinary success is ascribed to machines sent over from France, accompanied by French engineers.5

The failure of the English at Dunbar led to important consequences. It encouraged Sir Andrew Moray to lay siege to Stirling, and essentially contributed to animate the courage, improve the union, and augment the numbers of the Brucian party.

1This poem I picked up at York, at a bookseller’s shop, near the venerable Minister, on the tower of which I spent an agreeable hour, gazing on those vast ridings, as vast as some of the German principalities.

2The sow was a military engine, resembling the Roman testudo. It was formed of wood covered with hides, and mounted on wheels, so that being rolled forwards to the foot of the besieges wall, it served as a shed, or cover, to defend the miners, or those who wrought the battering ram, from the stones and arrows of the defenders. Border Min. i. 40.

3Salisbury even consented to a cessation of arms, and departing into the south, intrusted the care of the Borders to Robert Manners, William Heron, and other Northumbrian barons.

4Often so called in Records of times. – Ridpath.

5Fordun says, that the Governor prevailed in the siege of the fortresses mentioned, by the dread of a certain engine called Boustour. – Ridpath.

Other people associated with Dunbar Castle

Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scots, wife of King James I of Scotland, who served as the Regent of Scotland in the immediate aftermath of his death and during the minority of her son James II of Scotland, before being engulfed in a power struggle with members of the nobility. In desperation she took refuge in Dunbar Castle where she was subsequently besieged by her opponents, in which place and circumstances she died in the year 1445.

Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany, second son of King James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders, was Duke of Albany, Earl of March, Lord of Annandale and Isle of Man and the Warden of the Marches, which altogether gave him an impressive power base in the east and west borders, centred on Dunbar Castle which he owned and lived in. He attempted to seize control of Scotland from his brother King James III of Scotland, but was ultimately unsuccessful.

John Stewart, Duke of Albany, de facto ruler of Scotland and important soldier, diplomat and politician in a Scottish and continental European context, was the only son of the above Duke of Albany, and managed where his father had failed and became Regent of Scotland, while he also became Count of Auvergne and Lauraguais in France and, lastly, inherited from his father the position of Earl of March, which allowed him to likewise use Dunbar Castle as his centre of power in Scotland

James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, notorious third and last husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, and owner of Dunbar Castle. He took Mary to Dunbar Castle after their marriage and there she was delivered of stillborn twins.

Further Reading

Watch Arte’s À Dunbar, n’énervez pas la comtesse !Invitation au voyage. (In French or German).

Dunbar Castle has had a very complex history involving Britons, Scots, French, Angles, etc. The Victoria Harbour entrance was blasted through the castle rocks and the Cromwell Harbour lies next to the now blocked old entrance. The Tide Gauge stands at the side of the present harbour entrance.