A lockdown walk to explore the area where my great (x3) grandparents Nicol Selkirk and Elizabeth Hume Wood lived and worked.

Nicol Selkirk and Elizabeth Hume Wood

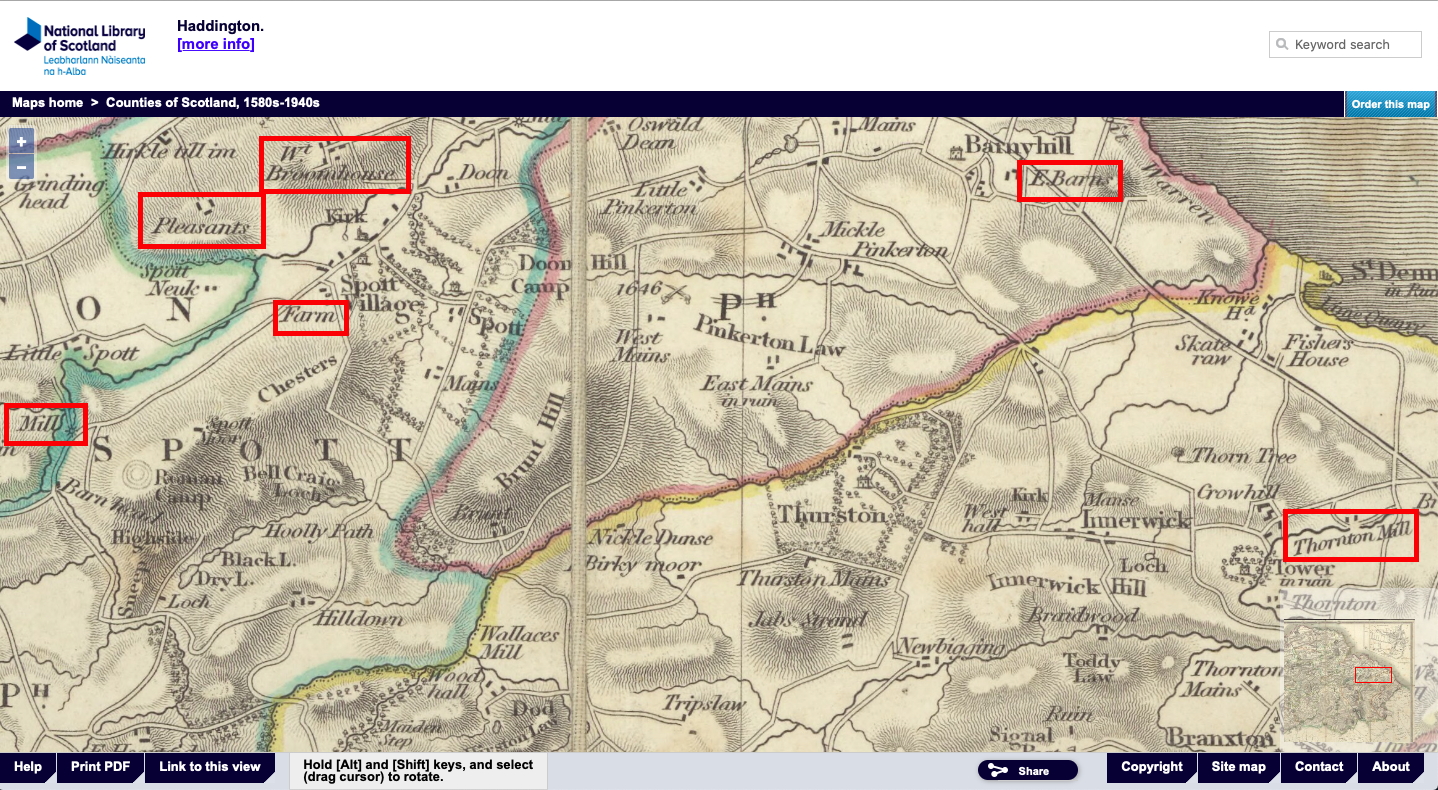

When we first moved to Dunbar in 1974, I had no idea that my father’s family had local roots. His ancestors the Woods lived at East Barns, to the east of Dunbar from at least 1788. Meanwhile, the Selkirks were from Prestonpans and Tranent mining stock, but before 1809 they left the mines and became farm workers in places around Dunbar including East Barns, Wester Broomhouse, Pleasance, Spott, Spott Mill and Thornton Mill.

The Birth and of Nicol Selkirk in Tranent parish

Nicol Selkirk was born in the parish of Tranent in the county of East Lothian in Scotland on 02 May 1783 and baptised there on 11 May 1783. The witnesses to the baptism were Robert Kinly (most likely his paternal grandfather or possibly his maternal uncle) and a Mr Turcan. The second witness was John Turcan (1718-1799), the son of the Rev Alexander Turcan and Anne Robertson. He was schoolmaster at Tranent for half a century, and also a kirk elder and precentor. He married his cousin, Beatrice Turcan, the daughter of another John, who had succeeded his father, the above William Turcan, as a farmer at Tulliallan. Our John Turcan’s aunt, Mary Robertson was married to William Adam the foremost Scottish architect of his time, and their son (and John’s cousin) was Robert Adam, the celebrated neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer.

The Birth of Elizabeth Hume Wood at East Barns in Dunbar parish

Elizabeth Hume Wood was born at East Barns, in the parish of Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland on 09 May 1791 and she was baptised on 15 May 1791 with witnesses John Cowe (her maternal grandmother’s brother-in-law) and James Wilson Amily (her maternal grandfather). She appears to have been named “Hume” in honour of her father’s employer, Mr Robert Hume who became tenant of East Barns in 1781 when he inherited the tack of his brother, William Hume.

Marriage in Dunbar

On 22 December 1809, Nicol Selkirk and Elizabeth Hume Wood were married in the town of Dunbar, in the parish of Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland. While Nicol Selkirk had moved around East Lothian, Elizabeth Hume Wood may have lived at East Barns for all of her life until then. When Nicol Selkirk married Elizabeth Hume Wood on 22 December 1809, he was working as a Labourer at an unstated place in Dunbar parish.

East Barns, Dunbar parish

According to the 1855 entry in the Old Parish Register of Births & Baptisms, on 09 October 1813, when their son Robert was born, on 24 January 1814 at the birth of their son John and on 14 January 1816 at the birth of their son James, Nicol Selkirk was working as a Hynd at East Barns, in parish Dunbar. A Hynd was a married, skilled farm worker who occupied a cottage on the farm and was granted certain perquisites in addition to his wages.

The Selkirks seem to have remained at East Barns until at least 19 March 1820 when their son William was baptised.

The Pleasance (or Pleasants), Spott parish

By 08 September 1823 when their daughter Margaret was baptised, they were living at The Pleasance (then known as Pleasants), in the Church of Scotland’s parish of Spott. They were still living at the Pleasance on 24 March 1833 when their tenth and final known child, Elizabeth was born.

Wester Broomhouse, Spott parish

At the census of 06 June 1841, Nicol Selkirk was recorded as being aged 50 (actually 58), working as a Agricultural Labourer, and living at Wester Broomhouse, in the parish of Spott. Living with him was his wife Elizabeth and his children James, Nicholas (Nichol), Margaret, Alison and Elizabeth.

Spott Mill, Spott parish

At the census of 30 March 1851, Nicol Selkirk was recorded as aged 67, working as an Agricultural Labourer and living at Spott Mill in Spott parish, East Lothian, Scotland. He was living with his daughter, Elizabeth, aged 20 (actually 18) and a farm servant. Nicol’s wife Elizabeth was visiting their son Robert and his family at Broadwoodside in Yester parish at the date of the 1851 census.

On 22 April 1855, Nicol Selkirk’s wife Elizabeth Hume Wood died at Spott Mill in Spott parish. This was the first year of Statutory Registration and a large amount of information was collected in that year only. She was recorded as being a Labourer’s wife, aged 64, having been born in the parish of Dunbar, and having lived in the current district for 12 years. Her parents were recorded as John Wood, Farm Servant and Alison Cockburn, also a Farm Servant. Alison Cockburn was actually Elizabeth’s step mother and had married Elizabeth’s father on 14 November 1794. Elizabeth’s mother, was Susan Emily, the daughter of Joshua Amler, a soldier and Agnes Bell. Susan had died after giving birth to a son, John Wood on 21 November 1792, and was buried at Spott kirkyard on 23 November 1792.

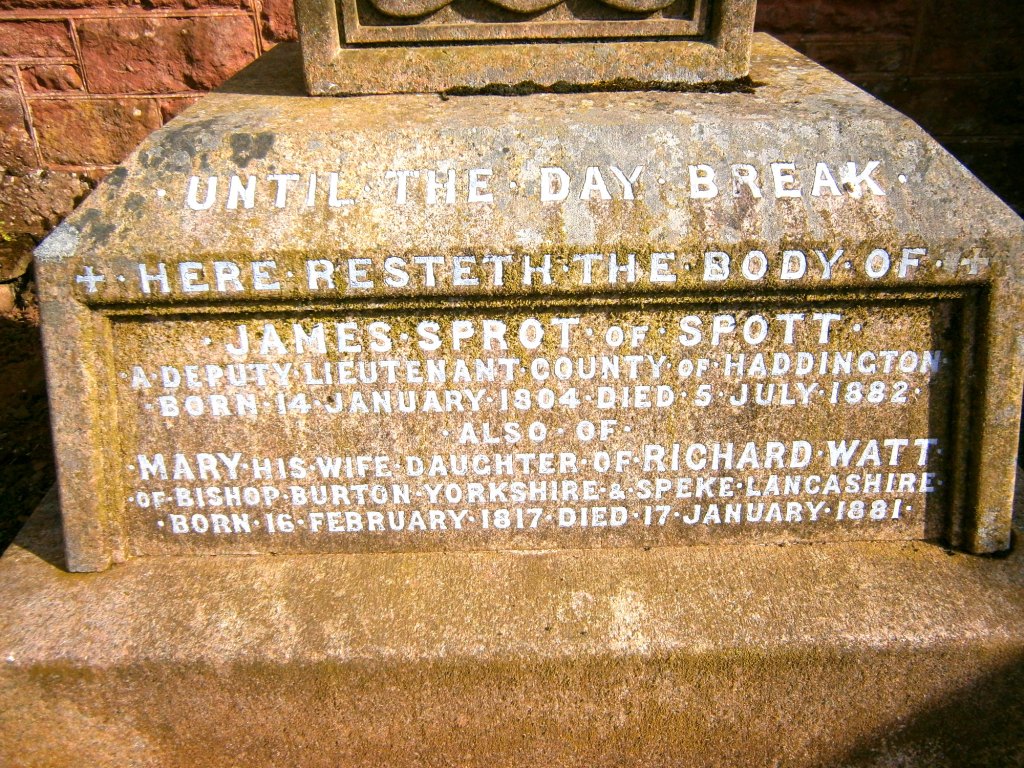

On Elizabeth Hume Wood’s death register entry, her children were listed as Robert aged 43, John aged 41, James aged 39, Susan aged 35, William aged 33, Margaret aged 31, Alison aged 27 and Elizabeth aged 24. The cause of death was given as Palsy, for 10 days, with the death certified by John Turnbull, Surgeon, who saw the deceased on 21st April 1855. She was buried in the churchyard of Spott (where her gravestone can still be seen) as certified by John Burnside, undertaker. The death was registered by her eldest son, Robert. Robert Selkirk had started off as a farm labourer but went on to become a Farm Steward and he managed the Home Farm for the Marquis of Tweeddale at Gifford. So, unusually for a family of farm labourers, he could afford to pay for a memorial stone.

Thornton Mill, Innerwick parish

At the census of 07 April 1861, Nicol Selkirk ws recorded as aged 76, formerly a Ploughman, and living at Thornton Mill, in the parish of Innerwick, East Lothian. He was living with his daughter Elizabeth, aged 26 (actually 28) and a farm labourer.

Spott Village, Spott parish

On 01 December 1868, Nicol Selkirk died in the village of Spott, in Spott parish, where he was buried beside his wife. He was recorded as being aged 86 years old, a ploughman and the widower of Elizabeth Wood, and the son of Robert Selkirk, ploughman and Catherine McKinlay. The cause of death was recorded as age and infirmity, as certified by James Dunlop F.R.C.S.E., Dunbar. The death was registered by his eldest son, Robert Selkirk.

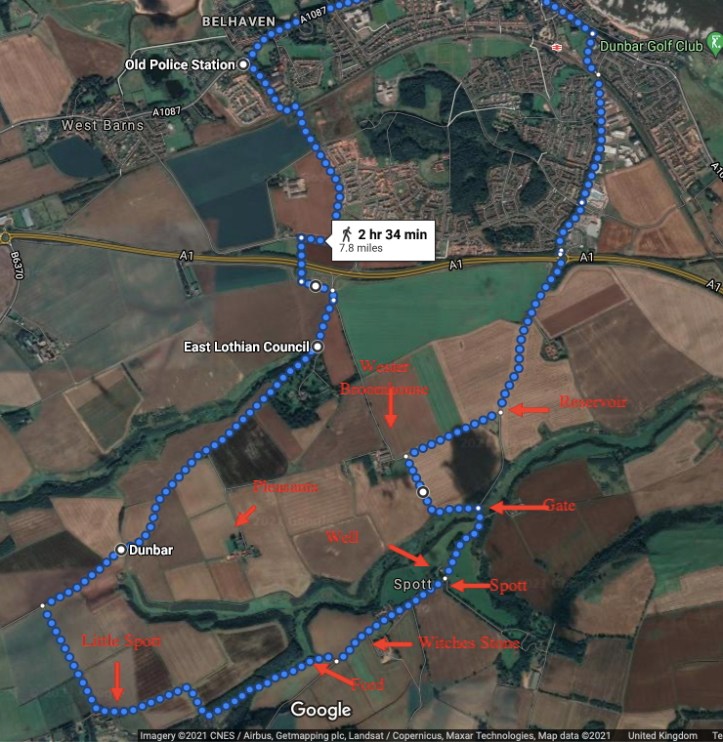

The Circular Walk

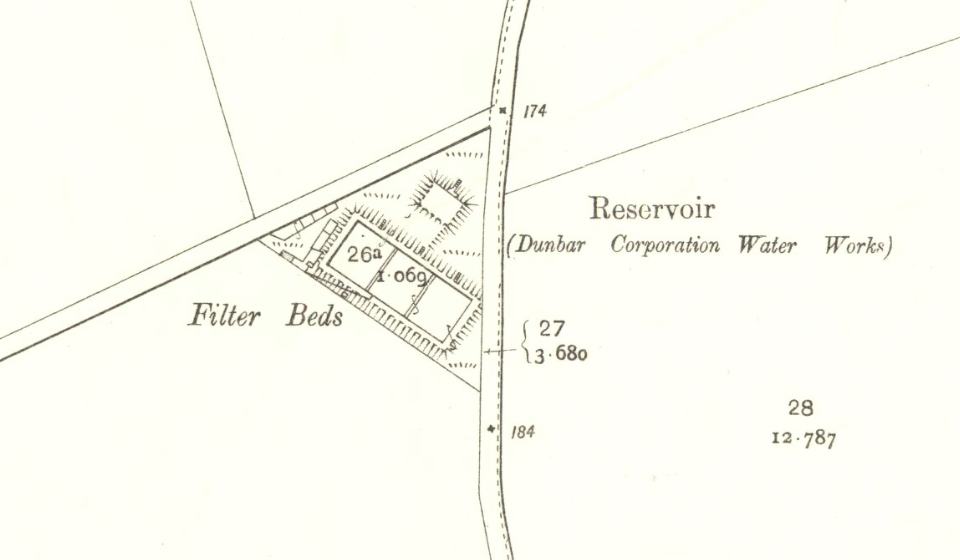

In Dunbar, I turned right just after the parish church, along Spott Road, crossed the A1 at the roundabout, and up the road to Spott, stopping the reservoir.

Dunbar’s Water Supply – The Filter Beds and Reservoir.

The reservoir provides an excellent viewpoint back to Dunbar. Dunbar received its first piped water supply in 1766 or 1767 when water from the spring at Saint John’s Well by Spott (see later) was brought to Dunbar.

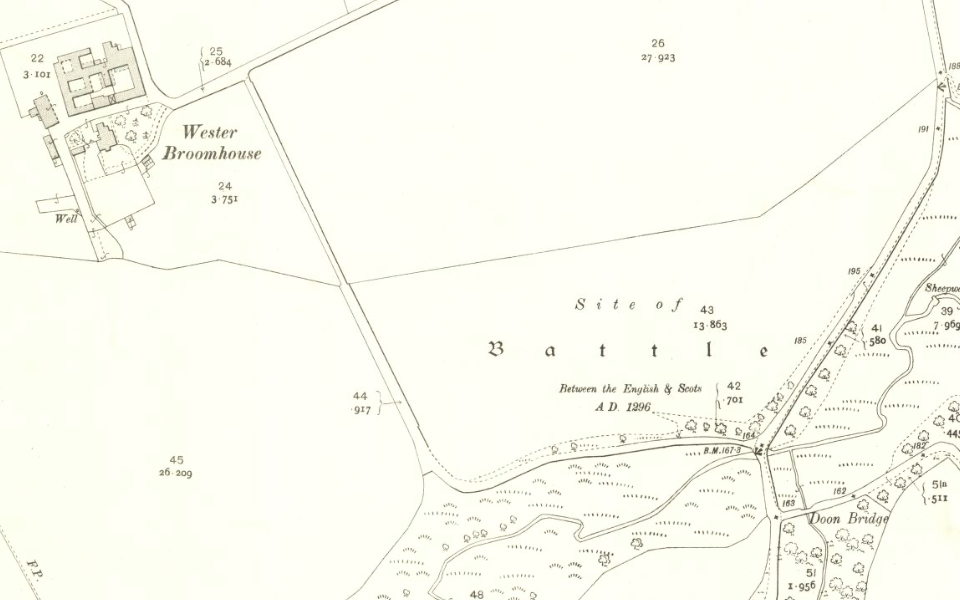

From Wester Broomhouse to Doon Bridge

At the reservoir, the road splits with the left hand branch heading to the farm of Western Broomhouse, where Nicol Selkirk worked, and the left hand branch going directly to Spott. I took the road to Wester Broomhouse, turning left just before the farm to head down the narrow lane towards Doon Bridge.

Several years ago, my father and I, following a route recommended by Google maps, drove down this road only to find our route blocked by a narrow and locked gate. As it proved impossible to turn the car – we even tried to lift the car – my father had to reverse all the way back up this hill!

The first Battle of Dunbar, 27 April 1296

The lane from Wester Broomhouse to Doon Bridge lies beside the site of the 1296 first Battle of Dunbar – see map above.

According to Sinclair, Robert (2013). The Sinclairs of Scotland. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9781481796231:

“There is little evidence to suggest that Dunbar was anything other than an action between two bodies of mounted men-at-arms (armoured cavalry). Surrey’s force seems to have comprised one formation (out of four) of the English cavalry; the Scots force led in part by Comyns probably represented the greater part of their cavalry element.

The two forces came in sight of each other on 27 April. The Scots occupied a strong position on some high ground to the west. To meet them, Surrey’s cavalry had to cross a gully intersected by the Spott Burn. As they did so their ranks broke up, and the Scots, deluded into thinking the English were leaving the field, abandoned their position in a disorderly downhill charge, only to find that Surrey’s forces had reformed on Spottsmuir and were advancing in perfect order. The English routed the disorganised Scots in a single charge.

The action was brief and probably not very bloody, since the only casualty of any note was a minor Lothian knight, Sir Patrick Graham, though about 100 Scottish lords, knights and men-at-arms were taken prisoner. According to one English source over ten thousand Scots died at the battle of Dunbar, however this is probably a confusion with the casualties incurred at the storming of Berwick.

The survivors fled westwards to the safety of the Ettrick Forest. The following day King Edward appeared in person and Dunbar castle surrendered. Some important prisoners were taken: John Comyn, Earl of Buchan, and the earls of Atholl, Ross and Menteith, together with 130 knights and esquires. All were sent into captivity in England.”

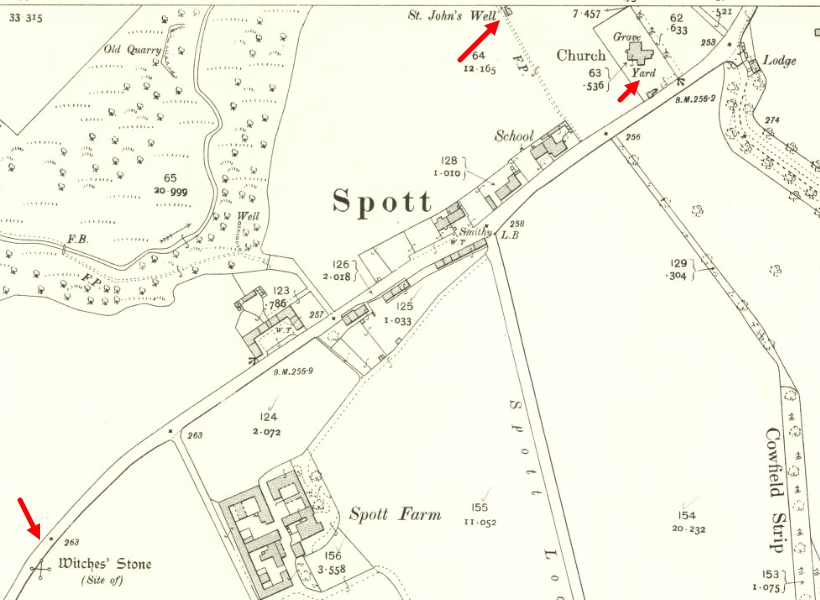

Spott and its Church

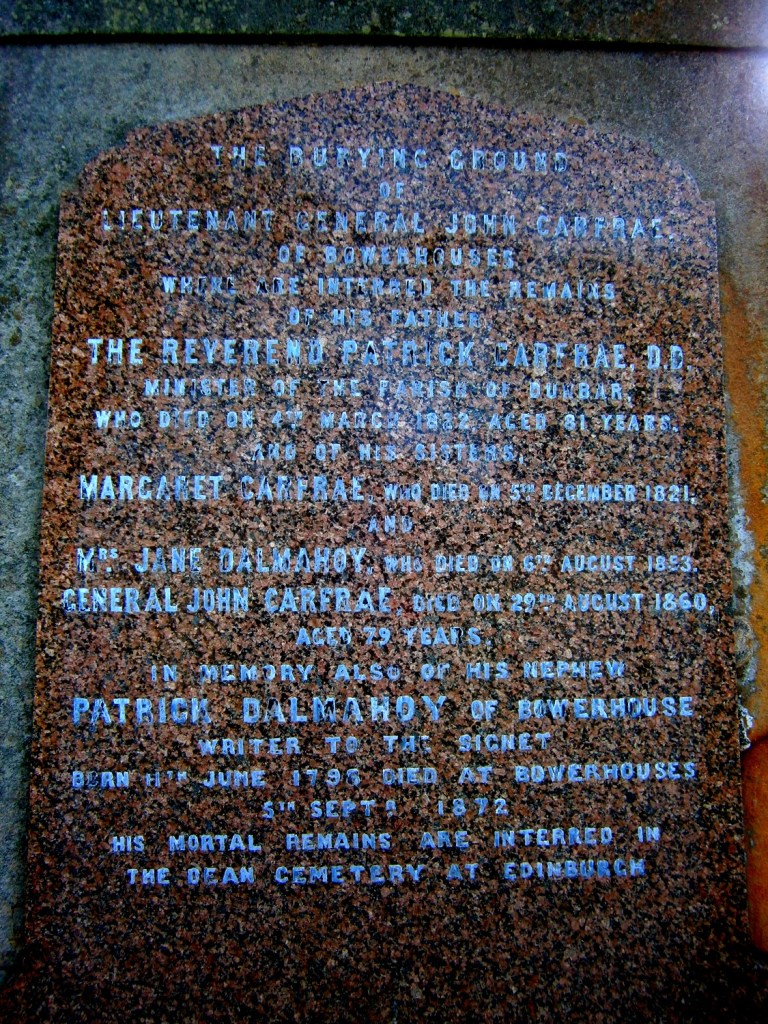

By foot, the gate, this time open, proved no obstacle to progress and I turned right up the Canongate and into the village of Spott. The origins of the current church are somewhat vague, but it is certain there was a church here before the Reformation, when Spott Kirk was a prebendary of the Collegiate Church of Dunbar. Major repairs were carried out on the church in 1790 and again the following century giving its present cruciform shape. One arm of the church is an ancient burial vault. In 1570 the minister, John Kelloe, strangled his wife in the manse before delivering ‘a more than usually eloquent sermon‘. He was executed on October 4 at Edinburgh at the Gallow Lee on Leith Walk for the crime. Patrick Simson, the Greek language expert, whose father was minister in Dunbar, preached here.

Spott graveyard

Spott House was originally a tower house, constructed in 1640, the family home of the Hays of Yester. It is reputed to have housed Oliver Cromwell during the Battle of Dunbar (1650). In 1830, it was purchased by James Sprot, who had the house remodelled by William Burn, the pioneer of the Scots Baronial style. The estate remained in the Sprot family until 1947, when it was sold to Sir James Hope. It was eventually sold to the Lawrie family, who sold it to the Danish-born Lars Foghsgaard in 2000.

Farming

Saint John’s Well

Saint John’s Well is described on Canmore: (NT 6727 7561) St John’s Well (NAT)

“There is a fine old holy well, dedicated to St John, 100 yds below Spott church.

J R Walker 1883; Trans E Lothian Antiq Fld Natur Soc 1929

St John’s Well: An excellent spring well from which the town of Dunbar is supplied with water by means of lead pipes. The waterworks were constructed in 1767 at a cost of £1,700.

Name Book 1853

The well, which is within a stone building, has been piped, and now issues about 20m to the N. There is a local tradition that the monks of Coldingham Priory (12th century: NT96NW 11) made an annual pilgrimage to this well (Rev D M Turner, Innerwick Manse).”

The well contains two vaulted chambers, one straight ahead and a second, pictured above, to the right.

The Old Statistical Account for the parish of Spott states: “On the banks of all the burns are excellent springs. St John’s Well in the neighbourhood of the village of Spott is the most remarkable. It is carried in pipes 2 miles to Dunbar, for the supply of water to the inhabitants.”

The second Battle of Dunbar, 3 September 1650

The Old Statistical Account for the parish of Spott also includes details of the second Battle of Dunbar in 1650: “Downhill, about 500 feet above the sea, is remarkable for being the place on which General Leslie had his camp before (what is sometimes called) the Battle of Dunbar, but in general over this county, the Battle of Downhill, fought on the east side and neighbourhood of the hill, between Oliver Cromwell, and the Scotch army under Leslie’s command. from this strong entrenchment Leslie was persuaded, contrary to his own opinion, to come down, and was defeated by Cromwell, who was just about to embark his troops at Dunbar for want of provisions, and pursued with great slaughter. Musket bullets, swords, human bones, and pieces of scarlet cloth are still found in the neighbouring fields; many of the killed were buried in and around Spott dean.”

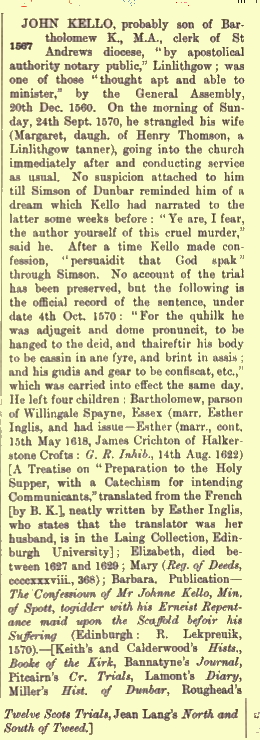

The Rev. John Kello.

One person who seems to have slipped the attention of the author of the Statistical account was the Rev. John Kello who was appointed Minister of Spott parish in 1567. On 24 September 1570, he strangled his wife then calmly proceeded to church and conducted a service. On 4th October 1570 at the Gallow Lee on Leith Walk he was executed for the crime in a similar way to those convicted of witchcraft: he was hanged until death and then his body was cast into a fire and burnt. His “goods and gear” were also confiscated.

Witchcraft

The Old Statistical Account for the parish of Spott stated: “1698: The session, after a long examination of witnesses, refer the case of Marion Lillie, for imprecations and supposed witchcraft, to the presbytery, who refer her for trail to the civil magistrate. Said Marion generally called The Rigwoody Witch.

Oct 1705, Many Witches burned at the top of Spott loan. The Presbytery meet at Spott, as a committee of censure on the minister, elders, heritors, schoolmaster, precentor, beadle and heads of families. According to usual form they were all severally removed, try’d, and approved. The minister particularly interrogated concerning the church, pulpit, bell, church utensils, manse, offices, stipend, schoolmaster’s salary. Everything necessary immediately ordered by the heritors. Lord Alexander Hay, son of the Marquis of Tweeddale, being for the first time present, as proprietor of Spott.“

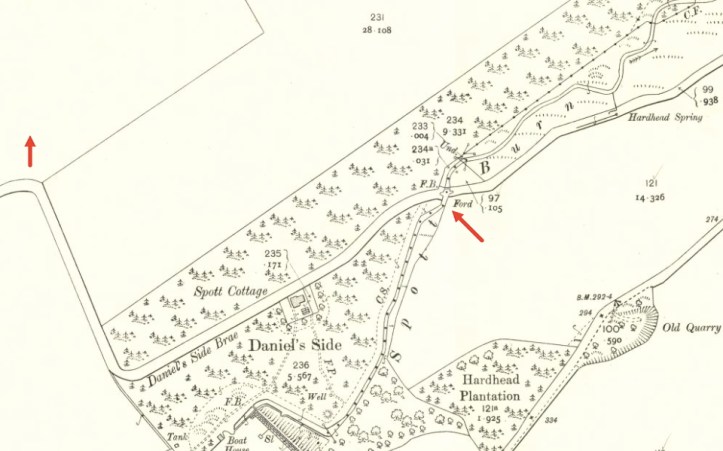

The Ford and Daniel’s Side Brae

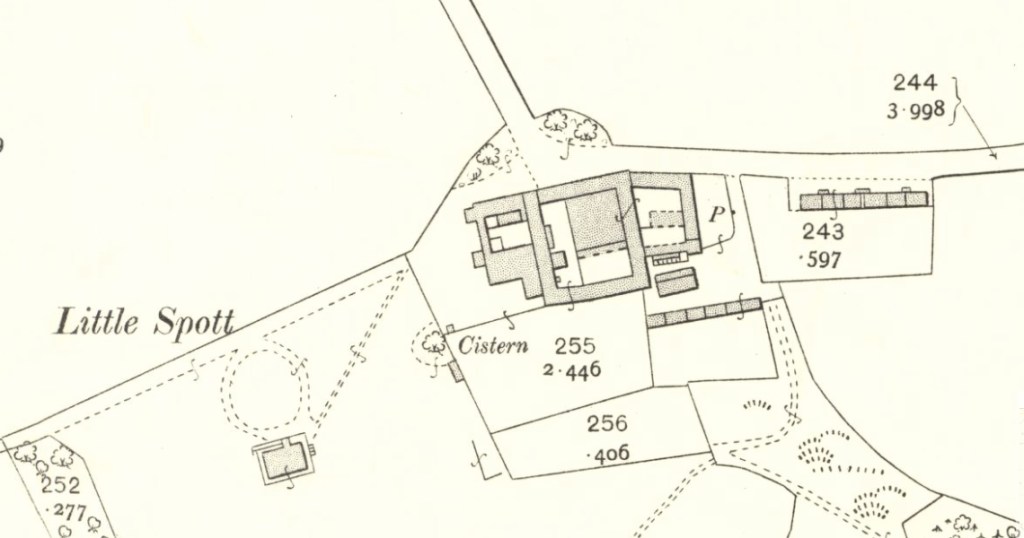

Little Spott

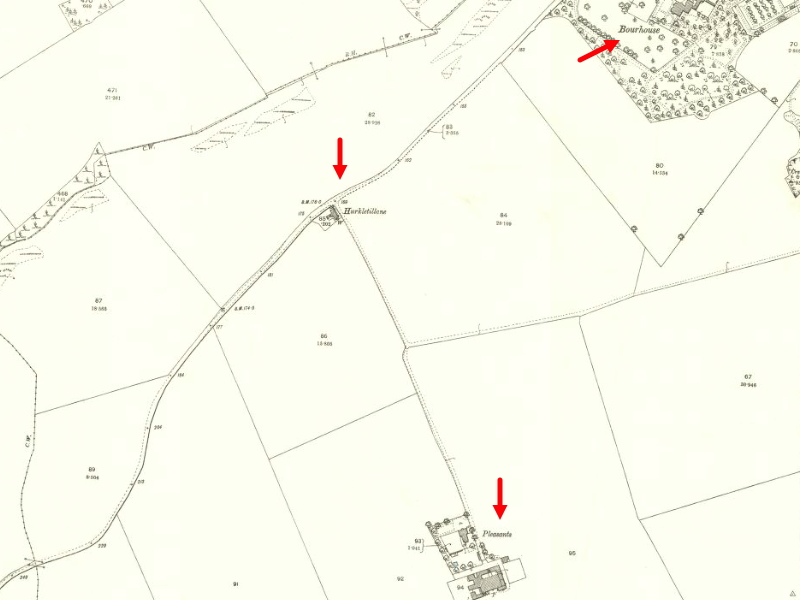

Hirkletillaine, Pleasants and Bourhouse