On this day, four hundred and forty one years ago, the Regent Morton was executed.

2 June 1581: The ex-Regent, James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, was executed for his alleged involvement in the murder of Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, Duke of Albany, second husband of Mary Queen of Scots and father of James VI, fourteen years earlier following accusations made by Mary Queen of Scot’s half-brother Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Orkney.

The Regents during the minority of King James VI

There were no less than four regents during the minority of King James VI, which lasted from 22 August 1567 until March 1578 when the Regent Morton resigned. On 10 March 1578 the eleven year old King issued a proclamation declaring that he would accept the burden of the administration personally and in September 1579 James VI was formally declared to have reached his majority and began his personal rule.

All four regents met with untimely ends. Two were shot, one died of natural causes, although some claimed he was poisoned, and the fourth was executed on a predecessor of the guillotine.

James Stuart, 1st Earl of Moray (Regent 22 August 1567–23 January 1570)

James Stuart, 1st Earl of Moray was the half-uncle of the King. Mary, Queen of Scots was forced into abdication at Loch Leven Castle on 24 July 1567, where she was imprisoned for more than nine months. Her half.brother, James Earl of Moray returned to Edinburgh from his exile in France on 11 August 1567 by way of Berwick-upon-Tweed. William Cecil, the English Secretary of State, had arranged his transport from Dieppe in an English ship.

The Earl of Moray was appointed as Regent of Scotland on 22 August for his half-nephew the infant King James VI (born 19 June 1566), son of Queen Mary and Henry, Lord Darnley, Duke of Albany & Earl of Ross. The appointment was confirmed by Parliament in December. To raise money, Moray sent his agent Nicolas Elphinstone to London to sell Mary’s jewels and pearls.

Mary, Queen of Scots escaped from Loch Leven on 02 May 1568, and the Duke of Chatelherault and other loyal nobles rallied to her standard. Moray gathered his allies and defeated her forces at the Battle of Langside, near Glasgow, on 13 May 1568. Mary was compelled to flee and decided to seek refuge in England. She could have departed for France, had she preferred, where she retained the status of a Queen Dowager, however her brother-in-law Charles IX, like his elder brother before him, was under the influence of his mother, Marie de’ Medici. When Mary had been Queen of France, her husband, François II‘s official acts all began with the words: “This being the good pleasure of the Queen, my lady-mother, and I also approving of every opinion that she holdeth, am content and command that …”.

For the subsequent management of the kingdom without Mary as Queen of Scots, the Regent Moray secured both civil and ecclesiastical peace and earned the title of “The Gude Regent“.

The Regent Moray was assassinated in Linlithgow on 23 January 1570 by James Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh, a supporter of Mary Queen of Scot. As the Earl of Moray was passing in a cavalcade in the main street below, Hamilton fatally wounded him with a carbine shot from a window of his uncle Archbishop Hamilton’s house.

The Earl of Moray was the first head of government to be assassinated by a firearm.

Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox (Regent 1570–04 September 1571)

Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox was the father of Lord Darnley and grandfather of the King. In May 1570, the Earl of Lennox returned to Scotland to assist the English in an attempt to recapture Edinburgh Castle, which was being held on Mary Queen of Scot’s behalf by William Kirkcaldy of Grange.

With the Regent Moray having been assassinated, the Earl of Lennox’s wife, Lady Margaret Douglas was pressing her cousin Queen Elizabeth of England to back Lennox as Regent for his grandson, James. Elizabeth reasoned that she could manipulate Lennox, who relied on his wife to handle all his negotiations with the English Government. He may not have proved politically astute, and the Earl of Morton to took effective control, but no one doubted his bravery. With Edinburgh Castle well defended, the Regent Lennox turned his attention to Dumbarton, which fell to him on 02 April 1571.

The Regent Lennox then faced a Hamilton-inspired rebellion with Mary’s supporters seeking her restoration. On 04 September, a raid on Stirling was led by the George Gordon, 5th Earl of Huntly, Claude Hamilton, and the lairds of Buccleuch and Ferniehurst. The Regent Lennox was shot in the skirmish and died of his wounds four hours later. His bleeding corpse was said to have made a lasting impression on his six-year-old grandson. Early reports reported that Lennox had been killed by his own party. William Kirkcaldy of Grange said the shot was fired by the Queen’s party, and another account named David Bochinant as the assassin.

John Erskine, 18th & 1st Earl of Mar (Regent September 1571-29 October 1572)

John Erskine, Earl of Mar (1571–1572) was a son of John, 5th Lord Erskine, who was guardian of King James V and afterwards of Mary, Queen of Scots. He was the maternal uncle of the Regent Moray despite being some twenty years younger than his nephew. He is regarded as both the 18th Earl of Mar (in the 1st creation) and the 1st Earl of Mar (in the 7th). He succeeded his father as 6th Lord Erskine in 1552 and in 1565 he was granted the earldom of Mar when Mary Queen of Scots restored the charter to him and his heirs “all and hail the said earldom of Mar.“

In September 1571 the Earl of Mar was chosen as Regent of Scotland, but like his predecessor, he was overshadowed and perhaps slighted by James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton.

The Regent Mar died at Stirling on 29 October 1572 after a short illness, widely agreed to have been natural causes. However, some sources indicate that he may have been poisoned at the behest of the Earl of Morton. Mar’s illness, according to James Melville, followed a banquet at Dalkeith Palace given by the Earl of Morton.

James VI continued to regard Mar’s widow Annabella Murray with affection and wrote to her as “Minnie“. She was the governess of his son Prince Henry at Stirling.

James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton (Regent 24 November 1572-March 1578)

James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton (1572–1581) was the last of the four regents of Scotland during the minority of King James VI. He was in some ways the most successful of the four, since he won the civil war that had been dragging on with the supporters of the exiled Mary, Queen of Scots. However, he came to an unfortunate end, executed by means of the Maiden, a predecessor of the guillotine.

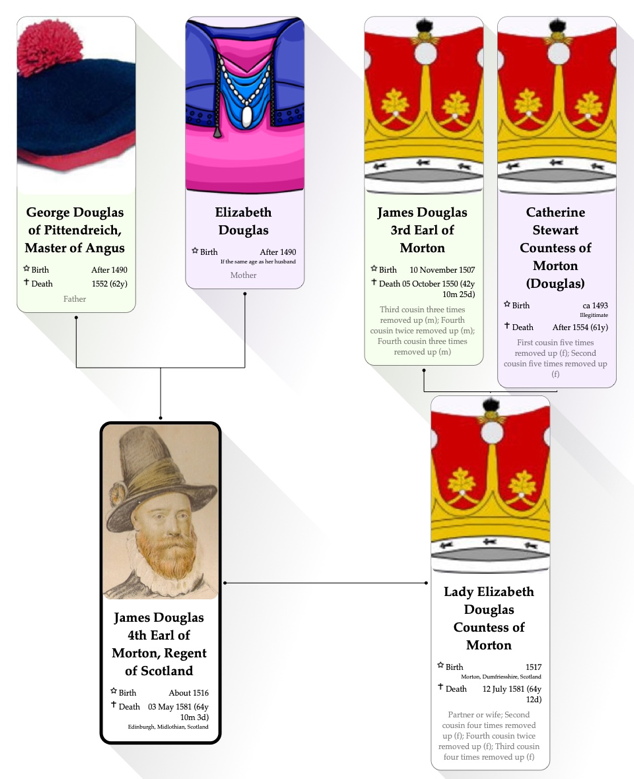

James Douglas was born the second son of Sir George Douglas of Pittendreich, Master of Angus, and Elizabeth Douglas, daughter of David Douglas of Pittendreich. He wrote that he was over 61 years old in March 1578, so was probably born around 1516.

Before 1543 he married Elizabeth, daughter of James Douglas, 3rd Earl of Morton. In 1553 James Douglas succeeded to the title and estates of his father-in-law, including Dalkeith House in Midlothian and Aberdour Castle in Fife. Elizabeth Douglas suffered from mental illness, as did her two elder sisters, who were married to Regent Arran and Lord Maxwell. James and Elizabeth’s children did not survive to adulthood, except three daughters who were declared legally incompetent in 1581. James also had five illegitimate children.

On 24 November 1572, a month after the death of Regent Mar, Morton, who had been the most powerful noble during Mar and Lennox’s rule, at last reached the object of his ambition by being elected regent. As Regent of Scotland, Morton expected the support of England and Elizabeth, and a week after his election, he wrote to William Cecil, Lord Burghley following his discussions with the English ambassador Henry Killigrew;

The knowledge of her Majesty’s meaning has chiefly moved me to accept the charge (the Regency), resting in assured hope of her favourable protection and maintenance, especially for the present payment of our men-of-war their bypast wages, “without the quhilk I salbe drevin in mony great inconvenientis.”

In many respects Morton was an energetic and capable ruler. His first achievement was the conclusion of the civil war in Scotland against the supporters of the exiled Mary, Queen of Scots. In February 1573 he effected a pacification with George Gordon, 5th Earl of Huntly, the Hamiltons, and other Catholic nobles who supported Mary at Perth, with the aid of Elizabeth’s envoy, Henry Killigrew. Edinburgh Castle still held out for Mary under the command of William Kirkcaldy of Grange and William Maitland of Lethington, and after a long siege the castle was taken on 27 May 1573, aided by English artillery and soldiers which finally arrived under William Drury.

The ensuing execution of the leaders of the Castle garrison men put an end to the last chance of Mary’s restoration by native support. In July 1573 Morton had the king’s chamber at Stirling Castle panelled, 60 new gold buttons made for his clothes, and gave him a football. He made efforts to recover jewels belonging to Mary which were held by Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray and others.

While all now seemed to favour Morton, under-currents combined to procure his fall. The Presbyterian clergy were alienated by his leaning to Episcopacy, and all parties in the divided Church disliked his seizure of its estates. Andrew Melville, who had taken over as leader of the Kirk from John Knox, was firmly against any departure from the Presbyterian model, and refused to be won by a place in Morton’s household. Morton rigorously pursued the collection of a third of the income from every Church benefice, a revenue that had been allocated to finance the King’s household. Morton had discretion to exempt persons and institutions from paying these thirds, and the historian George Hewitt found no striking evidence of bias in Morton’s exemptions.

In 1575 Morton obtained six “snaphaunce” musket hand guns from Flanders to serve as patterns for long guns called “calivers”. The Edinburgh gunmakers were ready to make 50 every week, they also made pistols called “dags” which equipped most of the gentlemen of Scotland. He sent a goldsmith Michael Sym to London for tools for the royal mint. Sym was also sent to buy silver plate for Morton and have some rubies cut for him.

In 1577 Morton was granted the barony of Stobo. However, over the next few months, opposition to Morton grew led by the Earl of Argyll and the Earl of Atholl, both leading Roman Catholics and members of the Queen’s party, in league with Alexander Erskine of Gogar, governor of Stirling Castle and custodian of the young James VI.

Morton was finally forced to resign as Regent in March 1578, but retained much of his power. He surrendered Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood Palace, the Great Seal and the jewels and Honours of Scotland, retiring for a while to Lochleven Castle, where he busied himself in laying out gardens. On 10 March, James VI issued a proclamation recognising that many in Scotland ‘misliked‘ the regiment of Morton, who had now resigned, and James would now accept the burden of the administration. The King was eleven years old.

On 27 April 1578, by the action of John Erskine (son of Regent Mar) and his brothers, the Commendators of Cambuskenneth and Dryburgh, Morton gained possession of Stirling Castle and the person of the king, regaining his ascendancy. On 12 August 1578, the forces of his opponents faced his army at Falkirk, but a truce was negotiated by two Edinburgh ministers, James Lawson and David Lindsay, and the English resident Robert Bowes. A nominal reconciliation was effected, and a parliament at Stirling introduced a new government. Morton, who secured an indemnity, was president of the council, but Atholl remained a privy councillor in an enlarged council with the representatives of both parties. Shortly afterwards Atholl died (allegedly of poison) and suspicion pointed to Morton. His return to power was brief, and the only important event was the prosecution of the two Hamiltons who still supported Mary. In the spring of 1579, the Scottish government’s forces moved to crush the power of the Hamilton family in the west, and Claude Hamilton and his brother John Hamilton fled to England. Morton would later deny that this was his initiative. The final fall of Morton came from an opposite quarter.

In May 1579, at St Andrews, an eccentric called Skipper Lindsay publicly declared to Morton in the King’s presence during the performance of a play that his day of judgement was at hand. In September, Esmé Stewart, Sieur d’Aubigny, the king’s cousin, came to Scotland from France, gained the favour of James by his courtly manners, and received the lands and earldom of Lennox, the custody of Dumbarton Castle, and the office of chamberlain. The young James VI was declared to have reached his majority and formally began his personal rule with some ceremony in Edinburgh in September 1579, and the period of the Regents was concluded.

On 31 December 1580, an associate of Lennox, James Stuart, Earl of Arran, son of Lord Ochiltree and brother-in-law of John Knox, had the daring to accuse Morton at a meeting of the council in Holyrood of complicity in the murder of Darnley, and he was at once committed to custody in Holyroodhouse and taken to Dumbarton Castle in the Lennox heartland. Some months later Morton was condemned by an assize for having taken part in Darnley’s murder, and the verdict was justified by his confession that the Earl of Bothwell had revealed to him the design, although he denied participation, “art and part“, in its execution.

The Earl of Morton was executed on 02 June 1581. The method of his execution was the Maiden, an early form of guillotine modelled on the Halifax gibbet. According to tradition, he brought it personally from England, having been “impressed by its clean work“, but doubt has been cast on this. It was actually ordered to be made by Edinburgh’s Town Council in 1564, David Hume of Godscroft appears to have initiated the Morton legend in his History of the House of Douglas (1644). His corpse remained on the scaffold for the following day, until it was taken for burial in an unmarked grave at Greyfriars Kirkyard. His head, however, remained on “the prick on the highest stone”, (a spike) on the north gable of the ancient Tolbooth of Edinburgh (outside St Giles Cathedral), for eighteen months until it was ordered to be reunited with his body in December 1582. Morton’s final resting place is reputedly marked by a small sandstone post incised with the initials “J.E.M.” for James Earl of Morton. The post is more probably a Victorian marker for a lairage. In the very unlikely event that a marker were permitted for an executed criminal, the inscribed initials would have been “J.D.” and, secondly, it would have been cleared away in 1595 when all stones were removed from Greyfriars.

The Maiden

The Maiden in Fiction

“Look you, Adam, I were loth to terrify you, and you just come from a journey; but I promise you, Earl Morton hath brought you down a Maiden from Halifax, you never saw the like of her — and she’ll clasp you round the neck, and your head will remain in her arms.

“Pshaw!” answered Adam, “I am too old to have my head turned by any maiden of them all. I know my Lord of Morton will go as far for a buxom lass as anyone; but what the devil took him to Halifax all the way? and if he has got a gamester there, what hath she to do with my head?

“Much, much!” answered Michael. “Herod’s daughter, who did such execution with her foot and ankle, danced not men’s heads off more cleanly than this maiden of Morton. ‘Tis an axe, man, — an axe which falls of itself like a sash window, and never gives the headsmen the trouble to wield it.”

“By my faith, a shrewd device,” said Woodcock; “heaven keep us free on’t!”

Sir Walter Scott » The Abbott » Chapter 18

The Maiden is displayed at the National Museum of Scotland. The Maiden (also known as the Scottish Maiden) is an early form of guillotine, or gibbet, once used as a means of execution in Edinburgh, Scotland. (The word gibbet denotes several different devices used in capital punishment.)

The History of the Maiden

According to legend, the Maiden was introduced to Scotland during the minority of King James VI, from Halifax, West Yorkshire, in the north of England, by the Regent James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton. It is said that Morton borrowed the design from the Halifax Gibbet and carried a model of it from Halifax to Edinburgh. After it was built, it remained so long unused that it acquired the name of the Maiden. Morton was eventually executed by it himself in 1581, although contrary to legend he was not the first person to be executed by it.

Although the resemblance to the Halifax machine, and Morton’s role in introducing the Maiden are doubtful, the records of the construction of the Maiden survive. It was made in 1564 during the reign of Mary Queen of Scots.The accounts reveal that it was made by the carpenters Adam and Patrick Shang and George Tod. Andrew Gotterson added the lead weight to the blade. Patrick Shang was paid 40 shillings for his ‘whole labours and devising of the timber work.’ Shang also made furniture in Edinburgh, including an oak bed for Queen Mary’s half-brother, the Earl of Moray.

The first victim on record was Thomas Scott of Cambusmichael, as early as 03 April 1565. From 1564 to 1708 more than 150 people were executed on the Maiden, after which it was withdrawn from use.

Notable victims included Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll in 1661, executed following the Restoration of Charles II, and his son Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll in 1685, executed for leading a rebellion against James VII.

The Maiden’s Mechanism

The person under sentence of death placed his head on a crossbar which is about four feet from the bottom. Lead weights weighing around 75 pounds (34 kg) were attached to the axe blade. The blade is guided by grooves cut within the inner edges of the frame. A peg, which is in turn attached to a cord, kept the blade in place. The executioner removed the peg by pulling sharply on the cord, and this caused the blade to fall and decapitate the condemned. If the condemned had been tried for stealing a horse, the cord was attached to the animal which, on being whipped, started away removing the peg, thereby becoming the executioner.