Eighty years ago today, on the 10th May 1941, in one of the great unsolved mysteries of the second world war, the German Deputy Führer, Rudolph Hess parachuted into Scotland, apparently intending to meet Douglas Douglas Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton at his seat of Dungavel near Strathaven in South Lanarkshire.

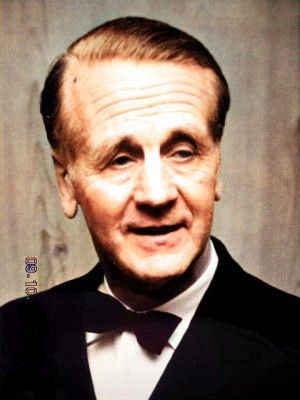

Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess served in that position until 1941, when he flew solo to Scotland in an attempt to negotiate peace with the United Kingdom during World War II. He was taken prisoner and eventually convicted of crimes against peace, serving a life sentence until his suicide in 1987.

As the war progressed, Hitler’s attention became focused on foreign affairs and the conduct of the war. Hess, who was not directly engaged in the war, became increasingly sidelined from the affairs of the nation and from Hitler’s attention. Hess decided to attempt to bring Britain to the negotiating table by travelling there himself to seek meetings with the British government.

HESS’ Flight to Scotland

On 31 August 1940, Hess was advised by his mentor Karl Haushofer that King George VI was opposed to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and would dismiss him and send him to Canada at the first opportunity. Haushofer suggested contacting the king via either General Ian Hamilton or Haushofer’s friend the Duke of Hamilton. Hess decided they should contact his fellow aviator the Duke of Hamilton, believing that he was opposed to war with Germany andn Hess’s instructions, Haushofer wrote to Hamilton in September 1940. The letter was intercepted by MI5 and the Duke of Hamilton did not see it until March 1941.

Despite not receiving a reply from Hamilton, Hess proceeded with his plan and began training on the Messerschmitt Bf 110, a two-seater twin-engine aircraft, in October 1940 under instructor Wilhelm Stör, the chief test pilot at Messerschmitt.

After several aborted attempts due to mechanical problems or poor weather, Hess finally took off at 17:45 on 10 May 1941 from the airfield at Augsburg-Haunstetten in his specially prepared aircraft. Initially setting a course towards Bonn, Hess used landmarks on the ground to orient himself and make minor course corrections. When he reached the coast near the Frisian Islands, he turned and flew in an easterly direction for twenty minutes to stay out of range of British radar. He then took a heading of 335 degrees for the trip across the North Sea, initially at low altitude, but travelling for most of the journey at 5,000 feet (1,500 m). At 20:58 he changed his heading to 245 degrees, intending to approach the coast of North East England near the town of Bamburgh, Northumberland. As it was not yet sunset when he initially approached the coast, Hess backtracked, zigzagging back and forth for 40 minutes until it grew dark. Around this time his auxiliary fuel tanks were exhausted, so he released them into the sea. Also around this time, at 22:08, the British Chain Home station at Ottercops Moss near Newcastle upon Tyne detected his presence and passed along this information to the Filter Room at Bentley Priory. Soon he had been detected by several other stations, and the aircraft was designated as “Raid 42”.

Two Spitfires of No. 72 Squadron RAF, No. 13 Group RAF that were already in the air were sent to attempt an interception, but failed to find the intruder. A third Spitfire sent from Acklington at 22:20 also failed to spot the aircraft; by then it was dark and Hess had dropped to an extremely low altitude, so low that the volunteer on duty at the Royal Observer Corps (ROC) station at Chatton was able to correctly identify it as a Bf 110, and reported its altitude as 50 feet (15 m). Tracked by additional ROC posts, Hess continued his flight into Scotland at high speed and low altitude, but was unable to spot his destination, Dungavel House, so he headed for the west coast to orient himself and then turned back inland. At 22:35 a Boulton Paul Defiant sent from No. 141 Squadron RAF based at Ayr began pursuit. Hess was nearly out of fuel, so he climbed to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) and parachuted out of the plane at 23:06. He injured his foot, either while exiting the aircraft or when he hit the ground. The aircraft crashed at 23:09, about 12 miles (19 km) west of Dungavel House. He would have been closer to his destination had he not had trouble exiting the aircraft. Hess considered this achievement to be the proudest moment of his life.

THE CAPTURE, interrogation and interment OF RUDOLPH HESS

Hess landed at Floors Farm, by Waterfoot, south of Glasgow, where he was discovered still struggling with his parachute by local ploughman David McLean. Identifying himself as “Hauptmann Alfred Horn”, Hess said he had an important message for the Duke of Hamilton. McLean helped Hess to his nearby cottage and contacted the local Home Guard unit, who escorted the captive to their headquarters in Busby, East Renfrewshire. He was next taken to the police station at Giffnock, arriving after midnight; he was searched and his possessions confiscated. Hess repeatedly requested to meet with the Duke of Hamilton during questioning undertaken with the aid of an interpreter by Major Graham Donald, the area commandant of Royal Observer Corps. After the interview Hess was taken under guard to Maryhill Barracks in Glasgow, where his injuries were treated. By this time some of his captors suspected Hess’s true identity, though he continued to insist his name was Horn.

The Duke of Hamilton had been on duty as wing commander at RAF Turnhouse near Edinburgh when Hess had arrived, and his station had been one of those that had tracked the progress of the flight. He arrived at Maryhill Barracks the next morning, and after examining Hess’s effects, he met alone with the prisoner. Hess immediately admitted his true identity and outlined the reason for his flight. Hamilton told Hess that he hoped to continue the conversation with the aid of an interpreter; Hess could speak English well, but was having trouble understanding the Duke of Hamilton. He told the Duke that he was on a “mission of humanity” and that Hitler “wished to stop the fighting“.

After the meeting, the Duke of Hamilton examined the remains of the Messerschmitt in the company of an intelligence officer, then returned to Turnhouse, where he made arrangements through the Foreign Office to meet Churchill, who was at Ditchley for the weekend. They had some preliminary talks that night, and Hamilton accompanied Churchill back to London the next day, where they both met with members of the War Cabinet. Churchill sent the Duke with foreign affairs expert Ivone Kirkpatrick, who had met Hess previously, to positively identify the prisoner, who had been moved to Buchanan Castle overnight. Hess, who had prepared extensive notes to use during this meeting, spoke to them at length about Hitler’s expansionary plans and the need for Britain to let the Nazis have free rein in Europe, in exchange for Britain being allowed to keep its overseas possessions. Kirkpatrick held two more meetings with Hess over the course of the next few days, while the Duke of Hamilton returned to his duties. In addition to being disappointed at the apparent failure of his mission, Hess began claiming that his medical treatment was inadequate and that there was a plot afoot to poison him.

From Buchanan Castle, Hess was transferred briefly to the Tower of London and then to Mytchett Place in Surrey, a fortified mansion, designated “Camp Z”, where he stayed for the next 13 months. In the early morning hours of 16 June 1942, Hess rushed his guards and attempted suicide by jumping over the railing of the staircase at Mytchett Place. He fell onto the stone floor below, fracturing the femur of his left leg. Hess was moved to Maindiff Court Hospital on 26 June 1942, where he remained for the next three years. Germany surrendered unconditionally on 8 May 1945. Hess, facing charges as a war criminal, was ordered to appear before the International Military Tribunal and was transported to Nuremberg on 10 October 1945. Hess was found guilty on two counts: crimes against peace (planning and preparing a war of aggression), and conspiracy with other German leaders to commit crimes. He was found not guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. He was given a life sentence, one of seven Nazis to receive prison sentences at the trial. These seven were transported by aircraft to the Allied military prison at Spandau in Berlin on 18 July 1947. Hess died on 17 August 1987, aged 93, in a summer house that had been set up in the prison garden as a reading room. He took an extension cord from one of the lamps, strung it over a window latch, and hanged himself.

ANALYSIS

Before his departure from Germany, Hess had given his adjutant, Karlheinz Pintsch, a letter addressed to Hitler that detailed his intentions to open peace negotiations with the UK. He planned to initially do so with the Duke of Hamilton, at his home, Dungavel House, believing incorrectly that the duke was willing to negotiate peace with Germany on terms that would be acceptable to Hitler. Pintsch delivered the letter to Hitler at the Berghof around noon on 11 May. After reading the letter, Hitler let loose an outcry heard throughout the entire Berghof and sent for a number of his inner circle, concerned that a putsch might be underway. Hitler stripped Hess of all of his party and state offices, abolished the post of Deputy Führer, and secretly ordered him shot on sight if he ever returned to Germany.

US journalist Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker, who had met both Hitler and Hess, speculated that Hitler had sent Hess to deliver a message informing Winston Churchill of the forthcoming invasion of the Soviet Union, and offering a negotiated peace or even an anti-Bolshevik partnership. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin believed that Hess’s flight had been engineered by the British. Stalin persisted in this belief as late as 1944, when he mentioned the matter to Churchill, who insisted that they had no advance knowledge of the flight. While some sources reported that Hess had been on an official mission, Churchill later stated in his book The Grand Alliance that in his view, the mission had not been authorized. “He came to us of his own free will, and, though without authority, had something of the quality of an envoy”, said Churchill, and referred to Hess’s plan as one of “lunatic benevolence”.

After the war, Albert Speer discussed the rationale for the flight with Hess, who told him that “the idea had been inspired in him in a dream by supernatural forces. We will guarantee England her empire; in return she will give us a free hand in Europe.” While in Spandau prison, Hess told journalist Desmond Zwar that Germany could not win a war on two fronts. “I knew that there was only one way out – and that was certainly not to fight against England. Even though I did not get permission from the Führer to fly I knew that what I had to say would have had his approval. Hitler had great respect for the English people …” Hess wrote that his flight to Scotland was intended to initiate “the fastest way to win the war“.

Douglas Douglas Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton

“When deputy Führer Hess came down with his aeroplane in Scotland on 10 May, he gave a false name and asked to see the Duke of Hamilton. The Duke, being apprised by the authorities, visited the German prisoner in hospital. Hess then revealed for the first time his true identity, saying that he had seen the Duke when he was at the Olympic games at Berlin in 1936. The Duke did not recognise the Deputy Führer. He had however, visited Germany for the Olympic games in 1936, and during that time had attended more than one large public function at which German ministers were present. It is, therefore, quite possible that the deputy Führer may have seen him on one such occasion. As soon as the interview was over, Wing Commander the Duke of Hamilton flew to England and gave a full report of what had passed to the Prime Minister, who sent for him. Contrary to reports which have appeared in some newspapers, the Duke has never been in correspondence with the Deputy Führer. None of the Duke’s three brothers, who are, like him, serving in the Royal Air Force has either met Hess or has had correspondence with him. It will be seen that the conduct of the Duke of Hamilton has been in every respect honourable and proper.“

Sir Archibald Sinclair, the Secretary of State for Air, Hansard, 22 May 1941.

In 1933, the 14th Duke of Hamilton participated in the British Houston Everest Expedition which was launched with the intention of being first to fly an aircraft over the world’s highest mountain. The expedition faced serious technology and flying challenges in open-cockpit biplanes.