Sir Walter Scott’s novel Bride of Lammermoor

“The story is a dismal one, and I doubt sometimes whether it will bear working out to much length after all. Query, if I shall make it so effective in two volumes as my mother does in her quarter of an hour’s crack by the fireside? But nil desperandum.”

(Sir Walter Scott, Letter to James Ballantyne)

The Bride of Lammermoor is a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott, published in 1819, one of the Waverley novels. The novel is set in the Lammermuir Hills of south-east Scotland, shortly before the Act of Union of 1707 (in the first edition), or shortly after the Act (in the ‘Magnum‘ edition of 1830). It tells of a tragic love affair between young Lucy Ashton and her family’s enemy Edgar Ravenswood. Scott indicated the plot was based on an actual incident. The Bride of Lammermoor and A Legend of Montrose were published together anonymously as the third of Scott’s Tales of My Landlord series. The story is the basis for Donizetti’s 1835 opera Lucia di Lammermoor.

The inspiration for The Bride of Lammermoor

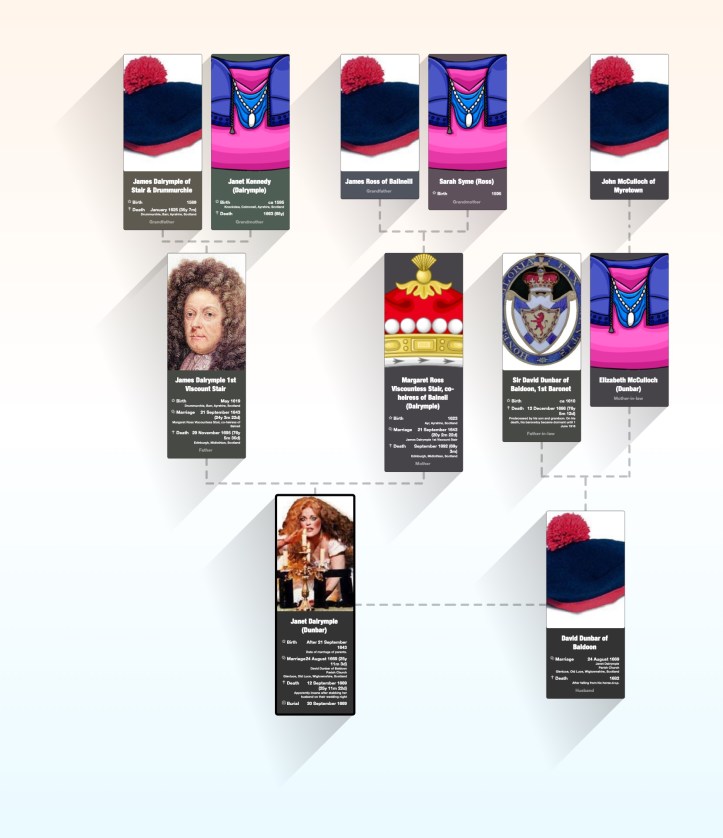

The story in The Bride of Lammermoor is fictional, but according to Sir Walter Scott’s introduction to the novel for the ‘Magnum‘ edition it was based on an actual incident in the history of the Dalrymple and Rutherford families. Scott heard this story from his mother, Anne Rutherford, and his great aunt Margaret Swinton. The model for Lucy Ashton was Janet Dalrymple, eldest daughter of James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount of Stair, and his wife Margaret Ross of Balneil. As a young woman, Janet secretly pledged her troth to Archibald, third Lord Rutherfurd, relative and heir of the Earl of Teviot, who was thus the model for Edgar of Ravenswood. When another suitor appeared – David Dunbar, heir of Sir David Dunbar of Baldoon Castle near Wigtown – Janet’s mother, Margaret, discovered the betrothal but insisted on the match with Dunbar. Rutherfurd’s politics were unacceptable to the Dalrymples: Lord Stair was a staunch Whig, whereas Rutherfurd was an ardent supporter of Charles II. Nor was his lack of fortune in his favour. Attempting to intercede he wrote to Janet, but received a reply from her mother, stating that Janet had seen her mistake. A meeting was then arranged, during which Margaret quoted the Book of Numbers (chapter XXX, verses 2–5), which states that a father may overrule a vow made by his daughter in her youth.

The marriage of David Dunbar and Janet Dalrymple went ahead on 24 August 1669, in the church of Old Luce, Wigtownshire, two miles south of Carsecleugh Castle, one of her father’s estates. Her younger brother later recollected that Janet’s hand was “cold and damp as marble”, and she remained impassive the whole day. While the guests danced the couple retired to the bedchamber. When screaming was heard from the room, the door was forced open and the guests found Dunbar stabbed and bleeding. Janet, whose shift was bloody, cowered in the corner, saying only “take up thy bonny bridgroom.” Janet died, apparently insane, on 12 September, without divulging what had occurred. She was buried on 30 September. Dunbar recovered from his wounds, but similarly refused to explain the event. He remarried in 1674, to Lady Eleanor Montgomerie, daughter of the Earl of Eglinton, but died on 28 March 1682 after falling from a horse between Leith and Edinburgh. Rutherfurd died in 1685, without children.

It was generally believed that Janet had stabbed her new husband, though other versions of the story suggest that Rutherfurd hid in the bedchamber in order to attack his rival Dunbar, before escaping through the window. The involvement of the devil or other malign spirits has also been suggested. Scott quotes the Rev. Andrew Symson (1638–1712), former minister of Kirkinner, who wrote a contemporary elegy “On the unexpected death of the virtuous Lady Mrs. Janet Dalrymple, Lady Baldoon, younger“, which also records the dates of the events. More scurrilous verses relating to the story are also quoted by Scott, including those by Lord Stair’s political enemy Sir William Hamilton of Whitelaw.

Scott’s biographers have compared elements of The Bride of Lammermuir with Scott’s own romantic involvement with Williamina Belsches in the 1790s. The bitterness apparent in the relationship between Lucy Ashton and Edgar of Ravenswood after their betrothal is broken has been compared to Scott’s disappointment when, after courting her for some time, Belsches married instead the much wealthier William Forbes.

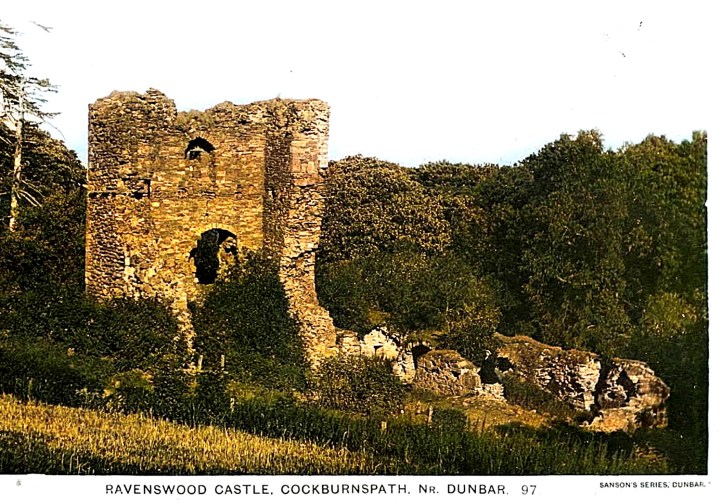

Locations

The spelling Lammermoor is an Anglicisation of the Scots Lammermuir. The Lammermuir Hills are a range of moors which divide East Lothian to the north from Berwickshire in the Scottish Borders to the south.

The fictional castle “Wolf’s Crag” has been identified with Fast Castle on the Berwickshire coast. Scott stated that he was “not competent to judge of the resemblance… having never seen Fast Castle except from the sea.” He did however approve of the comparison, writing that the situation of Fast Castle “seems certainly to resemble that of Wolf’s Crag as much as any other“.

Family Tree

David Dunbar of Baldoon was the great (x8) grandson of King Robert II of Scots via his daughter Princess Marjorie who married John de Dunbar 1st & 4th Earl of Moray.

The Donizetti opera – Lucia di Lammermoor

Celtic romance, a popular subject in the nineteenth century, was celebrated by Scott in his narrative poems, which were successful in translation throughout Europe. Turning later to the novel, often based on English history, he met with a similar success. On a visit to Paris in 1826, Scott attended a pastiche of his Ivanhoe (1820) with music by Rossini; more faithful versions of the story were composed by Marschner (Der Templer und die Jüdin, 1829) and Sullivan (1891). The first major Italian setting of Scott was Rossini’s La donna del lago (1819) based on the poem of 1810, the Lady of the Lake. This was followed by Donizetti’s Elisabetta al castelio di Kenilworth (1829) and the most successful setting of Scott, Lucia di Lammermoor (1835) based on The Bride of Lammermoor (1819). Notable French music derived from Scott includes the Waverley and Rob Roy overtures of Berlioz (1828, 1832) and Bizet’s unjustly neglected opera La joli fille de Perth (1867), after Scott’s The Fair Maid of Perth, 1828. While Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor is the best known opera inspired by Scott’s novel Bride of Lammermoor, there were four earlier and one later operatic versions:

- Adolphe-Charles Adam (1803 – 1856)

La Caleb de Walter Scott Paris, 1827 - Michele Enrico Carafa (1787 – 1872)

Le Nozze di Lammermoor Paris, 1829 - Luigi Rieschi (? – ?)

La Fidanzata di Lammermoor Trieste, 1831 - Ivar Frederik Bredal (1800 – 1864)

Bruden fra Lammermoor Copenhagen, 1832 - Gaetano Donizetti (1797 – 1848)

Lucia di Lammermoor Naples, 1835 - Alberto Mazzucata (1813 – 1877)

La Fidanzata di Lammermoor Padua, 1837

Lucia di Lammermoor, an opera by Gaetano Donizetti (1797 – 1848). Libretto by Salvatore Cammarano, based on Sir Walter Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor. Produced in Naples at the Teatro San Carlo on the 26 th September 1835. Miss Lucy Ashton (Lucia) loves the family enemy Sir Edgar of Ravenswood (Edgardo), but her brother, Lord Henry Ashton (Enrico) forces her to marry Lord Arthur Bucklaw (Arturo). When Edgar finds out, Lucy goes mad and kills Arthur. Edgar commits suicide from grief.

Musical highlights include:

Lucia’s aria, Regnava ne silenzio (Enveloped in silence).

Nadine Sierra – Lucia di Lammermoor “Regnava nel silenzio” – Donizetti: Tucker Opera Gala 2016

Lucia and Edgardo’s duet, Verranno a te sull’aure (Borne by gentle breezes).

Joan Sutherland and Alberto Kraus sing the duet of the first act of “Lucia di Lammermoor”, Metropolitan Opera.

Act II sextet, Chi mi frena in tal momento (Who restrains me at such a moment?).

Lucia di Lammermoor: “Chi mi frena in tal momento?”

Lucia’s Mad Scene, Alfin son tua (At last I am yours).

The mad scene from Act III of Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor.” Natalie Dessay (Lucia). Conductor: James Levine. Production: Mary Zimmerman.

Dame Joan Sutherland performing ‘Eccola!’ (The Mad Scene) from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor in the Australian Opera’s 1986 production at the Sydney Opera House.

Diva song from the Fifth Element – based on Lucia’s Mad Scene, Alfin son tua.

Edgardo’s aria, Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali (You who have spread your wings to heaven).

Jose Carreras sings the great final aria from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor.

Famous interpretations include:

Lucia: Lily Pons, Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, June Anderson, Cheryl Studer, Sumi Jo, Natalie Dessay.

Edgardo: Richard Tucker, Giuseppe DiStefano, Jose Carreras, Luciano Pavarotti.

Background:

To Italian audiences of the 1800’s, the lonely cliffs and ancient feuds of Scotland seemed a remote and exotic setting – and thus the perfect backdrop for an opera of tempestuous love and family honour. From Sir Walter Scott’s classic novel The Bride of Lammermoor, Donizetti fashioned one of his most passionate operas and mesmerizing heroines: Lucy (Lucia) Ashton, whose love for her family’s sworn enemy drives her to madness.

Long a favorite role of some of the world’s most famous sopranos, this bel canto masterpiece is a star vehicle for a singer of vocal suppleness and dramatic intensity.