One of the most celebrated events in archaeology was the the 1922 discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), one of the last kings of the 18th Dynasty by Howard Carter, whose work was funded by George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon. This resulted in the famous exchange where Carnarvon asked, “Can you see anything?” with Carter replying: “Yes, wonderful things!”

The ancient belief in a “Curse of the Pharaohs“, or “Mummy’s Curse” was highlighted in the 1920s due to the deaths of members of Howard Carter‘s team and other prominent visitors to the tomb.

The first of the mysterious deaths was that of Lord Carnarvon. He had been bitten by a mosquito, and later slashed the bite accidentally while shaving. It became infected and that resulted in blood poisoning. However, The Lancet concluded that Carnarvon’s death was unlikely to have any connection Tutankhamun’s tomb, refuting the theory that exposure to fungal toxins had accelerated to his death. The Lancet points out that the Earl was only one of many to enter the tomb, on several occasions and that none of the others were stricken by the curse.

Tutankhamun died in his late teens and one hypothesis was that he perished as a result of a chariot accident as a CT scan revealed that he had suffered a compound left leg fracture.

The CT scans of his mummy revealed that Tutankamun suffered from a cleft palate, and possibly scoliosis. He had a flat right foot and suffered from hypophalangism, while his left foot was clubbed and affected by bone necrosis of the second and third metatarsals (Freiberg disease or Köhler disease II).

Genetic testing through STR analysis rejected the hypothesis that he suffered from gynecomastia and craniosynostoses (e.g., Antley–Bixler syndrome) or Marfan syndrome.

Genetic testing for genes specific for Plasmodium falciparum revealed that Tutankhamun also suffered from malaria and the current hypothesis was that the malaria may have caused a fatal immune response in Tutankamun’s body or triggered circulatory shock.

The real Curse of the Pharaohs were genetic disorders caused by extreme endogamy with the royal family often marrying close relatives.

It was not until the study of genetics began in the early twentieth century that the harm caused by inbreeding was understood. Until then many dynasties believed inbreeding kept their lines pure with some extreme results such as the last Spanish Habsburg monarch, Charles II of Spain, being incapable of procreation and suffering from what was known as the Habsburg jaw.

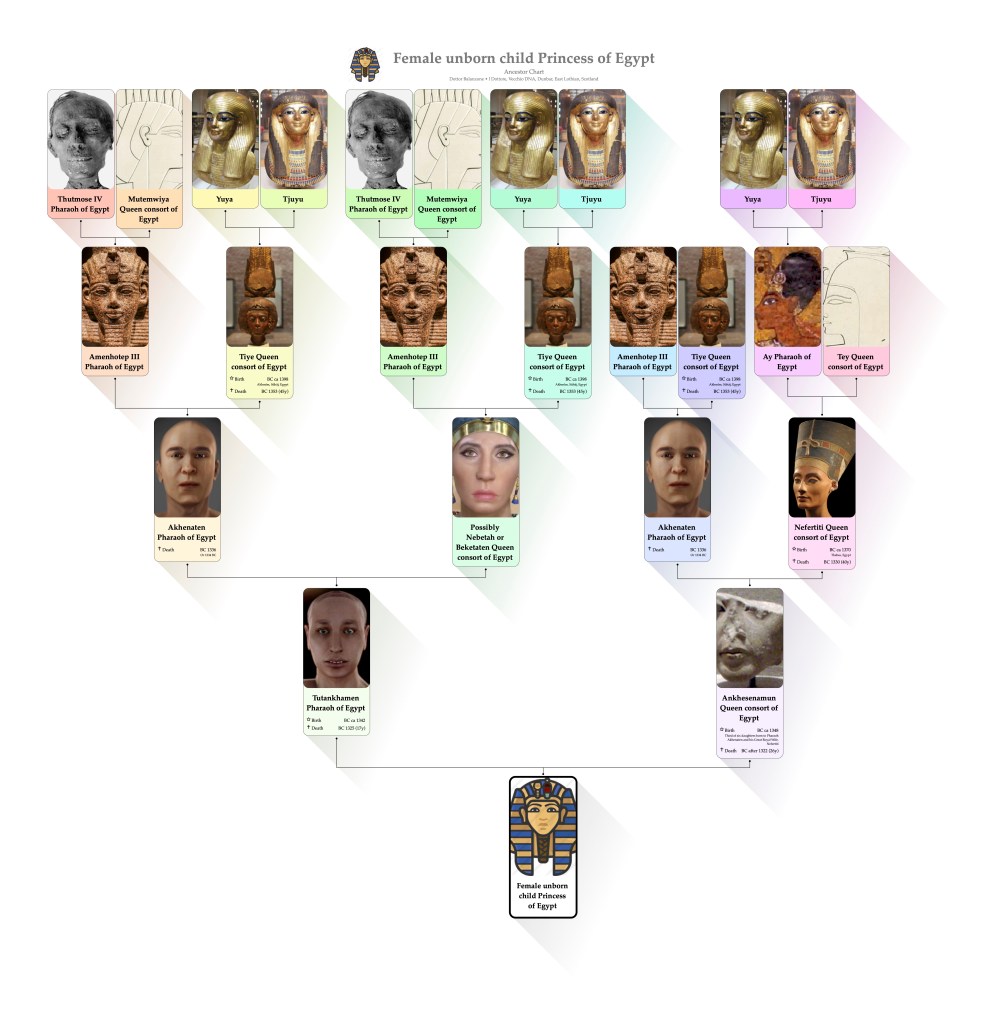

This endogamy is demonstrated by the family tree below detailing the ancestry of one of the two mummified unborn daughter of Tutankhamun.

DNA studies have helped reveal that Tutankhamun was the son of the “heretic” pharaoh Akhenaten (KV55) and one of Akhenaten’s five sisters, possibly Nebitah or Beketaten.

Tutankhamum married his half sister, Ankhasenamun, the daughter of Akhenaten and his famous consort, Queen Nefertiti, who was herself believed to be Akhenaten’s first cousin.

Therefore, while most people have four grandparents, eight great grandparents and sixteen great-great grandparents, Tutankhamun’s daughter only had three grandparents, four great-grandparents and six great-great-grandparents.

Further reading:

The Role of Inbreeding in the Extinction of a European Royal Dynasty

King Tut’s Family Secrets by Zawi Hawass in the National Georgaphic